Mechanic Slaps Town With Civil Rights Suit

A lawsuit that was to be filed in Federal District Court in Central Islip this morning charges that East Hampton Town officials, including a former town supervisor, a police lieutenant, two code enforcement inspectors, two town attorneys, and four former town councilpeople, conspired to deny a Montauk auto mechanic of his civil rights.

Although not named as defendants in the action, the suit includes a narrative that also points to the involvement of ad hoc citizens committee members, at least one a Democratic Party functionary. It also criticizes the town’s justice court for creating an environment that led to the abuse of governmental power.

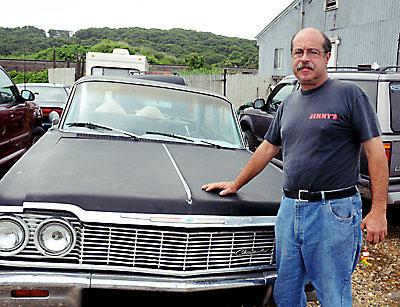

The suit was filed on behalf of Thomas Ferreira by Lawrence Kelly, a former federal prosecutor and United States State Department attorney from Garden City. It is Mr. Ferreira’s second legal action filed against the town in connection with the seizure and destruction of his belongings in June and September of 2009. In 2010, Mr. Ferreira filed an Article 78 action against the town in State Supreme Court charging that his constitutional rights to due process had been violated.

Mr. Kelly said during an interview on Saturday that in 2009 the East Hampton Town Board had acted as “a bizarre Star Chamber” that used illegal closed-door sessions to orchestrate a plan to oust Mr. Ferreira from his Navy Road property on Fort Pond Bay.

Mr. Kelly’s 64-page complaint alleges that the plan included a deliberate effort by the town attorney’s office to flout state law, suppress information, and circumvent the town’s court system in order to rid a gentrifying neighborhood of a legally preexisting garage using unauthorized code enforcement personnel to commit what he calls “economic extortion.”

Mr. Ferreira’s property, including over $100,000 worth of cars, car parts, and tools, was removed during two separate “enforcement actions” in June and September of 2009, and destroyed in the process by a contractor hired by the town. The town charged Mr. Ferreira $22,000 for removal of the vehicles and equipment. When he could not pay, a tax lien for that amount was applied to his property. It remains in effect today.

As part of a settlement agreement on Mr. Ferreira’s Article 78 action, the town had offered in February of this year to remove the lien, he said, upon him agreeing to hold the town harmless regarding the events that led to the removal of his property. He declined.

According to Mr. Kelly’s filing, neither visit was sanctioned by a warrant. When Mr. Ferreira asked East Hampton Town Police Sgt. Thomas Grenci to produce one during the June 22 seizure, he was threatened with arrest, the lawsuit claims.

The complaint alleges that Mr. Ferreira was denied a trial prior to the town’s seizures of his property for fear the proceedings would reveal that the numerous summonses issued to him, and to “hundreds if not thousands” of others, were issued by code enforcement personnel who were forbidden by state law to do so.

Mr. Kelly’s narrative goes on to assert that members of the Montauk Citizens Advisory and litter committees — both ad hoc bodies authorized by the town — conspired with agents of the town, including police, to remove Mr. Ferreira’s Automotive Solutions. The committee members were not named as defendants in the complaint, but were part of a narrative designed to reveal a pattern of what Mr. Kelly said was civil rights abuse.

Mr. Kelly said the Ferreira case revealed a clear pattern of business-as-usual during the McGintee administration.

The defendants named in the case are former Supervisor Bill McGintee, Peter Hammerle, Pat Mansir, Brad Loewen, and Julia Prince, former town board members, police Lt. Thomas Grenci, Madeline Narvilas, a former town attorney, John Jilnicki, the current town attorney, and the code enforcement inspectors Dominic Schirrippa and Kenneth Glogg. East Hampton Town as a whole is also named in the suit.

Only Ms. Mansir agreed to speak about this matter; the others named in the draft declined to comment or could not be reached.

One of the more potentially damning allegations involves a series of back-and-forth inspection reports and memos that appear to show Ms. Narvilas insisting that two reports — in which fire marshals cited no danger posed by the fuel in cars on Mr. Ferreira’s property — be replaced by one that declared “a potential catastrophe” — words she purportedly supplied to the fire marshal’s office in a June 19 memo.

According to Mr. Kelly, the replacement report was meant to diffuse any problems that could arise if the fire marshals’ original, positive, reports should leak out. If she could have gotten the fire marshal to sign on to it, it would also have been used in a complaint to be made against Mr. Ferreira in State Supreme Court, Mr. Kelly said. James Dunlop, the chief fire marshal, did not sign it.

Mr. Kelly alleges that the positive reports were not provided to the town board, specifically not to Ms. Mansir and Mr. Loewen, prior to the board’s passage, on June 18, of a resolution approving the June 22 visit to Mr. Ferreira’s property.

During a phone interview on Monday, Ms. Mansir confirmed Mr. Kelly’s assertion that the town board was not told about the fire marshals’ clean bills of health. Nor were members told, she said, that Mr. Ferreira’s car repair business was licensed by the state and was a legal pre-existing, nonconforming use of his property. She voted for the enforcement action with the rest of the five-member board, something she said she would not have done had she been given the missing information.

“There had to have been discussions. Maddie [Ms. Narvilas] was new to us. It had a bad overtone to me because of the Rian White situation,” Ms. Mansir said. As in the Ferreira case, belongings were taken away from Mr. White’s Springs property earlier the same year, and he was charged for the costs the town incurred to take away his belongings. “We relied on what was given to us,” Ms. Mansir said.

“I remember hearing that we, the town board, would not be told when they were going to do it. I was told it was a blight on the neighborhood with leaking fuel coming out of trucks and cars,” she said. “We were never told there was no danger from fuels. We were told we were upholding health, safety, and welfare, so leaking fuels would have been a danger.”

“That puts us very much in the wrong,” Ms. Mansir said. “They took his equipment and tools. I voted no when they put a lien on his property. I don’t think they did that legally. I’d like to know how concerned they were with leaking fuels when they crushed his cars right there on the beach.”

“When the government comes down on you, you carry it with you for the rest of your life. It went on for so long,” Ms. Mansir said.

In all, Mr. Kelly claims that the defendants violated Mr. Ferreira’s rights under the U.S. Constitution’s Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendments. There are six causes of action in total.

Mr. Ferreira was denied his right to due process under the Fifth Amendment, Mr. Kelly claims, because the town’s litter law, under which his client’s property was seized, was preempted by the New York State Property Maintenance Code that permits a mechanic to store cars and parts.

As of Jan. 1, 2003, the state’s property maintenance code superceded all municipal laws dealing with fire prevention, safety, and related matters. Municipalities could request special exemptions. Southampton did, for instance. East Hampton never sought an exemption to the general state law. As a result, “Major elements of the East Hampton Town Code became unenforceable regarding property maintenance and uniform building codes,” Mr. Kelly said, a fact he claims the defendants were aware of.

Furthermore, he claims, the town “encouraged unauthorized code enforcement inspectors to pick out areas of unenforceable town code to shape an instrument of oppression against Mr. Ferreira without any sworn affidavits, with illegal executive sessions, and without court scrutiny.”

The suit claims that Mr. Glogg, a code enforcement inspector, knowingly used the word “abandoned” in referring to the cars on the Ferreira property in his unsworn, unsigned report to the town board, evidence, Mr. Kelly wrote, of “evil intent, bad faith, and intentional and knowing misconduct. Cars used for their parts are, by definition, not abandoned. They were not ‘litter,’ ” he said, although the town’s litter code was used in the resolution authorizing the seizures of his property.

The Fifth Amendment also states that government cannot perform an “excessive taking,” that is seize private property for a public purpose without just compensation. Mr. Kelly claims the matter was never brought before a civil or criminal court for a review to determine probable cause for the seizures.

In his filing, Mr. Kelly refers to a 2011 statement made by Mr. Hammerle to The East Hampton Star. Mr. Hammerle stated that Mr. Ferreira had purposely delayed court proceedings on the charges against him. Mr. Ferreira claims his many requests for a trial were denied.

Mr. Kelly’s filing states that it was the intent of the individual members of the town board to avoid the courts and satisfy the Democratic Party vice chairwoman, Lisa Grenci’s, effort to rid the neighborhood of Mr. Ferreira’s repair shop.

Mr. Kelly said yesterday that Sergeant Grenci’s role should have been as a “neutral” in the June 2009 action. That role was “ethically conflicted” by his membership in the town’s litter committee, which was actively working to remove material from Mr. Ferreira’s repair shop. “There should have been a judge there,” Mr. Kelly said.

Mr. Kelly’s filing alleges that Lynden Restrepo, a broker of the Atlantic Beach Realty Group and also a member of the litter committee, told the town zoning board of appeals during a public meeting in February of last year that she was working closely with the town attorney’s office to use government resources against Mr. Ferreira.

The filing adds that Ms. Restrepo used “privileged information unavailable to the general public and in the custody and control of the East Hampton Town Police.”

Furthermore, the filing states that the town neglected to provide after-the-fact hearings regarding the impoundment of Mr. Ferreira’s property, which had been crushed at the scene of the seizures.

Mr. Kelly said on Tuesday that in addition to the town board’s abuse of the open meetings law, it was the failure of the court system to give Mr. Ferreira a trial that allowed the town’s unconstitutional methods to decide Mr. Ferreira’s fate.