A Mets Pinch-Hitting Legend Needs a Kidney

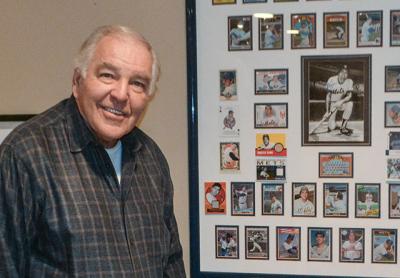

For five years running, Ed Kranepool was one of the best pinch-hitters in the history of Major League Baseball, the player New York Mets’ managers would turn to when they needed that one key hit in the bottom of the ninth to bail them out. Now it is Mr. Kranepool who is looking for a pinch-hitter.

He needs a kidney transplant, and after being unable to hunt for a donor for almost a year because of an infection, he is now clear to search in earnest for a match.

Mr. Kranepool, who lives in Old Westbury and has long docked his custom-built 65-foot power yacht on Three Mile Harbor, played for the Mets from the year the team was formed, 1962, through 1979.

While talking about his current health situation, Mr. Kranepool also reflected on his life in baseball.

His father died in the Battle of Saint-Lo in Normandy, less than four months before he was born, and his mother raised him and his older sister in the Bronx on a widow’s pension. When he was 10, he joined a Little League team coached by a neighbor, Jim Schiaffo, who had two sons in the league. “He was my guru. He treated me like a son.”

At James Monroe High School in the Soundview section of the Bronx, Mr. Kranepool starred in baseball and basketball. He was just 17 when he began his career with the Mets. The next youngest player in 1962 was 24, and his roommate, Frank Thomas, was 34. Mr. Kranepool acknowledged this week that the team, which lost over 100 games a year in their first four years, may have rushed his path to the majors.

“When you look back, when I had my best years, I finally caught up with the league. I hit .300. I should have hit .300 more often. At 17, when you are facing [Sandy] Koufax, [Don] Drysdale, and [Juan] Marichal, I don’t think you are mature enough, mentally and physically, to cope with that situation. And you have nobody to pal around with.”

While the media portrayed the Mets in those early years as lovable clowns, Mr. Kranepool and his teammates saw things differently. “People can say what they want. The Miracle Mets, the laughable Mets. That’s B.S. As a player, you want to win. You don’t want to have jokes made out of you. No matter what we did in the early years, it wasn’t good enough.”

He struggled for consistency at the plate, and was sent down to the minor leagues three times in his early years.

Then came the good times. The team added a nucleus of young talent, Hall-of-Fame pitchers like Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan. More important for Mr. Kranepool, he was suddenly surrounded in the lineup by true major league hitters. “Surround yourself with good hitters, you become a good hitter,” he said.

In 1969, the Mets won the World Series over the Baltimore Orioles, with Mr. Kranepool contributing a home run in game three. Still, he lacked consistency at the plate.

In 1970, Gil Hodges, the Mets manager who had played with Mr. Kranepool in 1962, ordered him sent down a fourth time. At 25, he considered retiring. He had been working during the off-season for a Wall Street brokerage firm. But M. Donald Grant, president of the club and an executive in the financial world, promised him that if he went down to the minors and did well, he would be brought back up. He hit .310 at Tidewater, and started the next season with the Mets. It was his best season in the majors up to that point, as he hit .280.

He was platooned, playing often against right-handed pitching, and went on to hit .300 or better twice. The Mets began using him as a late-inning pinch- hitter, a role in which he excelled.

He led the league in pinch-hitting five years in a row, including in 1974 when he set the all-time record for the pinch-hitting average for one season, going 17 for 35, or .486. “I was a good hitter. Mentally I could prepare myself. I knew what my job was.”

“I would warm up underneath,” he said. “I wouldn’t just sit there like I’m sitting here now, and then they call me in the eighth inning and say, ‘Here, pinch-hit.’ By the time you loosen up, you’re already out.”

Mets fans called him Steady Eddie, and, late in ballgames, with the game on the line, fans would chant, “Ed-die, Ed-die, Ed-die.”

In his final year on the team, he began to notice that his vision was sometimes blurry. He was diagnosed with diabetes the next year, when he was 36. His mother, too, had diabetes, but not until late in life.

Diabetes can affect the heart, the liver, the eyes, or the lungs, he said. “It attacks all your organs,” he explained at his house in Old Westbury on Friday. In his case, it is ravaging his kidneys, and without a transplant, he will need to go on dialysis.

Until last year, Mr. Kranepool and his wife, Monica, spent summers on their custom-built boat at Halsey’s Marina on Three Mile Harbor, which was their jumping-off point for other excursions farther afield. But last year, because of an infection in a bone in his left foot, which ultimately cost him all five toes on that foot, he had to see a nurse seven days a week. It was only toward the end of the season that he was cleared to visit Three Mile Harbor one day a week.

The infection put his search for a donor on hold. “When you have an infection,” he said, “they won’t do a transplant.” To minimize chances of a patient rejecting a healthy kidney, conditions have to be 100 percent optimal before doctors will perform a transplant. Until three weeks ago, there was no point in putting Mr. Kranepool’s prospective donors through the testing process. Now that has changed.

If a donor is found, the transplant will be done at Stony Brook University Hospital, which performs between 60 and 70 kidney transplants a year, with a success rate of 90 percent, after one year.