Montauk: An Early 20th-Century Village

A diorama of Montauk’s original fishing village is the first thing visitors see when they walk through the door of the East Hampton Town Marine Museum on Bluff Road, Amagansett. There’s a reason. Nothing represents the history of fishing in Montauk better than the community on Fort Pond Bay of hardy fishing families, which was all but wiped out by the 1938 Hurricane.

CLICK TO SEE MORE IMAGES

Ralph Carpentier of Springs is the artist who set out in 1965 to create the museum on behalf of the East Hampton Historical Society. The fishing village was “an important place,” he said recently. Important and colorful.

The residents of the old habitat are mostly gone now, but they had a lot to say about it in their time. They told about Prohibition days — or, more properly, nights — when fishermen met bootlegging boats offshore and brought crates of booze ashore to be stored in the village until trucks came to distribute it to the west.

There were the stories about “frost cod,” actually whiting left beached on falling tides, which was collected in buckets during the winter months.

In summer, the Shinnecock ferry visited the bay on its rounds to and from New London, Greenport, Sag Harbor, and Montauk. She is anchored in the bay in Mr. Carpentier’s diorama.

The late Gus Pitts, one of the fishermen who emigrated from Nova Scotia to Montauk in the early 1900s, was videoed in the 1980s talking about his life in the old village. His father had come to the South Fork to work on the bunker (menhaden) boats, large steamers out of Promised Land on Napeague, and stayed, to settle in Montauk. (The video can be borrowed from the Montauk Library.)

In 1914, as a young man, Captain Pitts was among the first residents of the village. He and his family rode out the 1938 Hurriane up the hill in the Montauk Manor. He recalled returning to the village to find “26 houses and 14 boats on top of each other, demolished.”

“Some were put back on their foundations,” Captain Pitts said. Other people were afraid the devastation would be repeated and moved away from the bay. But the village lived on in a reduced state until the Navy chose Fort Pond Bay as a site for a torpedo testing range during World War II.

These days, it’s hard to imagine life in Montauk’s original downtown. There were no cars, no lights, no lumber, no nails. Houses were heated with kerosene, if the family could afford it, or with wood from fish boxes and driftwood. “The train engineers were our friends. We supplied them with fish and they would dump coal beside the tracks that we collected in buckets,” Captain Pitts said.

The one-room school had a stove. “The teacher would tell us to go get seaweed or run to the tracks for coal.” There were 25 kids in grades one through eight. Ice was harvested from nearby Tuthill Pond for Parsons Fish Market and to keep fish cold while waiting at the freight house on the west end of the village. Captain Pitts said sea bass was kept alive in floating wooden containers until the end of the season when the price rose.

Boats were often blown aground in northeast storms. “They would be repaired and launched again.” He said it was not uncommon for crews to swim out to their boats.

And then there was Doc Edwards, who visited the village from East Hampton either on horseback (changing horses at the Napeague Life-Saving Station) or by a “railroad push car” powered by two men. Captain Pitts said David Edwards delivered 85 percent of the babies in Montauk.

Such was life on the unprotected bay until the developer Carl Fisher dynamited dunes on the north end of Lake Montauk to create the Montauk Harbor Inlet.

In Mr. Carpentier’s diorama, visitors can see the railroad dock, a siding that extended into the bay. Fish bound for New York City were loaded directly from boat to railroad car. The dock is near where the soldiers returning from the Cuban campaign in the Spanish-American War, including Col. Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Rider volunteers, came ashore from ships in 1896, headed to Montauk’s Camp Wikoff to recuperate.

Captain Pitts described how a few of the houses had been built using fish boxes and Army surplus boxes that had served as stalls on the railroad flatcars that brought the troops’ horses to Montauk.

The first packing houses on Fort Pond Bay were owned by E.B. Tuthill and Jake Wells. Perry B. Duryea Sr. bought out the Wells business in 1916 and the Perry B. Duryea and Son lobster business buildings are about the only remnants of the original village after the 1938 Hurricane.

The fishing village is “where it all began in the late 1800s,” Mr. Carpentier said. “I found in my research it’s where trawl fishing was first used. There were beam trawls before, but the otter trawls started in Fort Pond Bay in the 1890s,” he said, referring to the evolution of fishing using a net dragged from a boat.

“When I designed the museum I was committed to presenting the history of fishing in East Hampton — whaling and fishing. I wanted a frontispiece.” And so the diorama was launched.

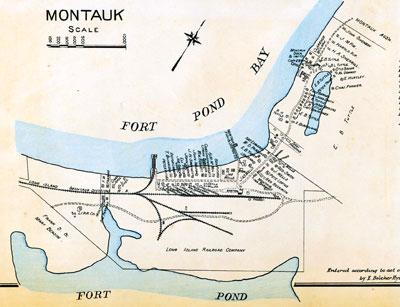

The designer insisted on authenticity. “I came across a map done in 1912 that had names of cottages and houses, and the names of people who built them. I decided to organize the names and called around to see if people had photographs. It was incredible. Everyone seemed to have had cameras back then.”

“They had photos. We had meetings once a week in Montauk. They would discuss what color a house was. ‘It was red.’ ‘No, it was green.’ I explained, we’ll ask three or four people and if more say it was green, that’s what it will have to be. That’s how we did it, from photos, even what the roofline was like.”

“The East Hampton Historical Society wanted a [marine] museum. The town got the building from the General Services Administration. It had been a Navy barracks. ”

“I was haulseining on the beach with Ted Lester at the time. I knew all the bubbies, and I knew a few of the draggermen. It all fell into place.”

The work it took to construct the train stations, tracks, docks, packing houses, the little houses and their satellite privies, was done by a number of people. Mr. Carpentier said he received $10,000 from the historical society to complete the diorama.

To help visitors from away get their bearings, the rear wall of the diorama is a map of the East End of the South Fork from Sag Harbor to Montauk. Standing in for the waters of Fort Pond Bay in the diorama is a piece of clear, wavy plexiglass under which Mr. Carpentier placed a piece of plywood painted blue. “I got lucky on that. I got it from a catalog. I think it was shower curtain. It worked well.”

The diorama has been moved into the entryway on the right side, the first exhibit museumgoers see as they come in through the front door. Mr. Carpentier said he approved of the move and of the other improvements made to the museum in recent months.

“It used to be a place where the old fishermen hung out. Whenever I needed, they were there for me. It used to be that young mothers hung out there. The kids would play on the lawn,” Mr. Carpentier said. He said it was something he’d like to see happen again.