‘The Most Valuable Fish That Swims’

The East Hampton Library could hardly have found a more suitable incarnation of local history than the old waterman Bruce Collins to close out its inaugural Tom Twomey lecture series on Saturday. Speaking off the cuff with only the aid of old maps and photographs, many of which he himself had donated to the library, Mr. Collins kept a sizable audience, which had renounced the season’s last 80-degree afternoon to hear him, enthralled.

Promised Land, that eastern arc of Amagansett on Gardiner’s Bay where menhaden-processing factories once thrived, was Mr. Collins’s ultimate destination, but he took a short detour along the way to talk about oysters. Not so very long ago, he said, the North and South Forks had a huge oyster industry, so huge that on a visit to Greenport in 1937 he remembers seeing “piles of oyster shells as big as two-story houses.” (So it looked to a 7-year-old, anyway.)

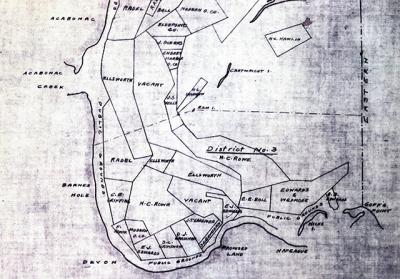

Oysters were prized depending on where they came from, he said, and some of the finest were found in the waters between Old Fireplace Road in Springs and Gardiner’s Island. In those days town governments leased out the bottomlands around Peconic and Gardiner’s Bays to private parties and a few companies, who would stake out their territory to warn off trespassers. Mr. Collins thinks the rental moneys may have gone to the local school districts. In any event, he recalled, grimacing, “it was a nightmare running a boat through there, especially at night. You might get a tree trunk stuck up through the boat.”

Dennis Fabiszak, the director of the library, who was manning the PowerPoint screen, flashed a close-up of a 1930s-era map showing some of the leased oysterbeds. “That’s the only map of its kind I’ve ever seen,” said Mr. Collins, but for whom the map would never have seen the light of day.

He explained why: “In the winter of 1960, I was a town councilman. The ground was frozen, but then we had a warm spell, and a pond developed,” near where Goldberg’s is now. “Water built up and got into the conduit, which came into the cellar of Town Hall. The basement was flooded. Hundreds of documents — books, records, surveys — were covered with mud. They were loading them into cars and throwing them out.”

He spotted the old map in thesoggy mess. “I asked Bill Bain, the supervisor, if I could have it. He said it was old and no one used it anymore. I took it home and cleaned it up.”

A few years ago, Mr. Collins got a phone call from Mr. Twomey with a question about fishing, “and it ended with him saying, ‘So, I’ll see you at 4 p.m. Friday,’ ” when the library’s board of directors was to meet. “I’ve never been a library person,” he said, but he went to the meeting anyway and then became a member of the board. Then he discovered the library’s highly regarded Long Island Collection, which pretty soon came to include the rescued map.

Mr. Collins, who spent some of the most memorable years of his life on menhaden-fishing steamers, was surprised to find that the collection contained nothing about the Promised Land processing factories, once such a huge contributor to the economy of eastern Long Island that the area had a postal address of its own.

“These fish were put on the face of the earth just to feed other fish,” he said, as a blown-up photo of a menhaden — people here say “bunker” or “mossbunker” — came on the screen. “They have no teeth. They swim in huge schools with their mouths open. You can cast into a school of a million bunkers all day long and never catch one. They’re not going to take your lure.”

“When you’re eating swordfish at Gosman’s, you’re really eating bunkers.”

Menhaden fleets catch the oily, bony fish “by the billions” every year, said Mr. Collins; in the past by hand, now with a crane and hydraulic block controlling the enormous nets. “Setting light, without fish, the boat draws five feet; loaded it draws 12 feet to the bow. At times I’ve seen the fish so heavy that they actually take the boat underwater.”

Ten boats, with about 280 men, himself among them, fished out of Promised Land from 1954 to 1960. In a conversation on Sunday, Mr. Collins recalled how he, the son of a man who owned a retail fuel business, came to be on the water: “From the age of 15, every summer in high school, I went on lobster boats. I ran one of Emerson Taber’s boats at age 17. Later I went as crew with Cap’n Carl Erickson, the best trawlerman I ever knew. We fished here in summer and Morehead City, N.C., in winter.” He never went to college.

“In ’54, Cap’n Jack Edwards called me. He wanted me to come on the Shinnecock with him, as coast and harbor pilot.” Mr. Collins was stunned by the offer, he said. “Most of these pilots were in their late years. I was 23.” But he studied up for his U.S. Merchant Marine master pilot rating and was licensed to work from Eastport, Me., to Port Isabel, Tex.

It was his job, he told Saturday’s audience, to “bring the steamer — they’re diesel-driven but we still call them steamers because the original boats were steamers — up against the set and not lose thousands of dollars worth of fish.” Menhaden, said Mr. Collins, are “arguably the most valuable fish that swims, used in maybe 400 or 500 products. Fertilizer, lipstick, margarine, paints of all kinds, pharmaceuticals, turkey pellets. . . .”

The catch was pumped out at the factory, which went by several names, he said: Smith Meal, Atlantic Processing Company, Seacoast Industries. “They were pumped into a big perforated screen and passed over a weighing scale and counted, so we knew at the end of every trip how many we’d got. We flew a U.S. flag on the last trip of the summer because we were the high boat — 30 million fish.”

The fish were pressed in a contraption almost like a wine press, Mr. Collins said, that squeezed out the oil. “The dry part went on to be ground up, and that was used for cattle feed and such.” One hundred percent protein, “it was sent out of here by tanker carloads. Purina, etc., bought it.”

“When that place was cooking you could smell it from here,” he told his listeners, many of whom nodded in recognition. “It just drove the summer colony crazy.”

Mr. Collins has given the Long Island Collection a good number of his photographs and papers relating to Promised Land and the trawlers that supplied it. (There has been much conjecture about the name of the place, but he said it was called that as long ago as the late 19th century, “by black crews from the South. They felt the fish here, especially in the fall with cold water, had more oil than any other fish and brought in more money.”)

Mr. Collins got a huge hand.

Smith Meal shut down in 1968. The factory was taken down and the company sold, to Hanson Ltd., a big industrial complex in England. Today, only one menhaden-processing plant remains on the East Coast, in Reedville, Va. The company, Omega Protein Inc., was fined $7.5 million two years ago under the Clean Water Act for discharging pollutants and harmful amounts of oil into Chesapeake Bay.