Mr. Inscrutable

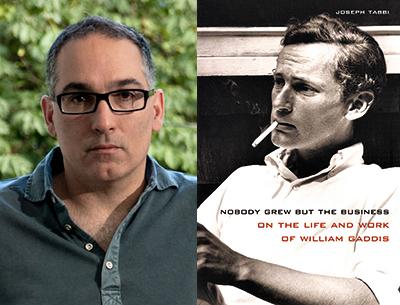

“Nobody Grew

but the Business”

Joseph Tabbi

Northwestern University Press, $35

Just imagine for a moment that you have the most useless job in the world: to set up a list of painful and impossible theses for literary critics to explore. The top of your torture list of prospective titles might read a lot like Joseph Tabbi’s new book, “Nobody Grew but the Business: On the Life and Work of William Gaddis.”

Many readers, after all, find Gaddis’s work some of the most difficult in contemporary literature, and his life is certainly one of the more elusively lived and recorded among celebrated American authors. To then try to conjoin these two unfeasible elements seems an almost masochistic undertaking.

Yet Mr. Tabbi, a professor of English at the University of Illinois at Chicago, has attempted just that. In most ways he has defied the odds; his “Nobody Grew but the Business” is a compact yet satisfying work and should be the final word (it won’t be) on a certifiable American genius.

One of the things that make a book like this so daunting is how little is known about the life of William Gaddis. This has less to do with the idea that the novelist was hiding, a la Thomas Pynchon, than the fact that for most of his life nobody was looking.

His first novel, “The Recognitions,” was published when Gaddis was 33. It was a book rife with ambition, rich with myth, and weighing in at a mammoth 956 pages; arguably, it was a masterpiece. But it was misunderstood by readers and critics alike, and soon fell out of print.

Gaddis then toiled in copywriting jobs for 20-odd years while compiling his next opus, “JR.” This second work captured the National Book Award, along with stronger reviews, but again mostly eluded the public’s imagination (as did Gaddis himself). It is really not until his slender but effective 1985 novel, “Carpenter’s Gothic,” that the public began to develop an interest in the author himself.

By then, however, he was 63, with much of his life past him. Gaddis was, until that time, a man little noticed and even less written about. To say the public record is thin is an understatement of grand proportions.

Furthermore, Gaddis was an intensely private man, as his collected letters, published in 2013, will attest. They are frustratingly reticent. And if all this weren’t enough, throw in this quote from “The Recognitions” concerning the artist, which also functioned as Gaddis’s lifelong credo: “What do they expect? What is there left of him when he’s done his work? What’s any artist, but the dregs of his work? The human shambles that follows it around?”

So Mr. Tabbi has a dearth of material to work with, yet among the great pleasures of his book are the little biographical nuggets that he has managed to pan from the life of this most private of artists. One fascinating recollection is a quote from Alice Denham, a friend of Gaddis’s during his copy-writing years who recalls the author saying, “Pfizer’s not too bad. They let Dick [Dowling] and me write all morning on our own stuff and show us off to clients as ‘our novelists.’ ” This seems a rare glimpse into a different era of corporate culture, if not an astonishing divergence in the way America used to value the written word.

Mr. Tabbi also settles, once and for all, Gaddis’s expulsion from Harvard (an event that has engendered endless speculation). Late in his third year, Gaddis apparently “violated ‘parietal rules,’ ” Mr. Tabbi writes, “meaning he had a girl in his room.” This was aggravated by another incident later on involving a night of drinking where a friend injured his hand on a pane of glass. Gaddis went outside to a phone booth to call for help and was apparently interrupted by a nosy policeman whom Gaddis dismissed with an expletive. Though this is a long way from the legend — which sometimes included Gaddis taking a swing at the officer — it certainly solidifies his cantankerous and anti-authoritarian reputation.

And like most complex men, there lurked a surprising corollary to the crotchety persona. Mr. Tabbi includes remembrances from students of Gaddis’s during the late 1970s when he was teaching his long-running course at Bard titled “Failure in American Literature” (a quintessentially Gaddisian title). One student recalled how Gaddis smoked continuously through his lectures, but did so considerately, positioning himself near the windows so as not to annoy nonsmokers, and even “cadged” a cigarette or two from students.

Another recalled Gaddis’s helpfulness as a mentor during a senior thesis project, remembering him as “pleasant and patient with me during our weekly meetings, and generous with suggestions for editing and his time concerning students’ work and direction.” Gaddis the team player!

The enduring revelation of Mr. Tabbi’s book, however, is just how stridently autobiographical much of the novelist’s writing was. “The Recognitions” apparently contained long stretches of dialogue lifted entirely from Gaddis’s own coterie of friends, as if he were taking notes. “Carpenter’s Gothic” takes place in the same town, and even the very same house, that Gaddis inhabited in the late 1970s. The same for “A Frolic of His Own” — the action unfolding in the very same Wainscott home he shared with a girlfriend in the 1980s.

We learn that the play “Once at Antietam,” included in its entirety in “Frolic,” was something Gaddis himself wrote many years before in hopes of having it dramatized. Mr. Tabbi is also convincing in his assertion that many of Gaddis’s heroines correspond directly to women in the author’s life, and finally there is Mr. Tabbi’s overview of “JR”: “The more one reads, in letters and notes from the early period,” he writes, “the more autobiographical ‘JR’ seems, even as Gaddis’s life, like the life of his characters, becomes overwhelmed by the transformations within his world.”

Implicit in Mr. Tabbi’s research is that part of Gaddis’s lust for privacy might have a good deal to do with how much of himself he was revealing on the page. What is there left of him when he’s done his work?

Mr. Tabbi is notably strong on the enduring impact of “JR” (Gaddis’s 1975 takedown of capitalism), and is right to proclaim that the novelist was prescient about the increasingly ubiquitous corporatization of America and the world. And he’s especially good at linking America’s current movement toward populism with the novel’s early diagnosis of an encroaching greed. (I, for one, had no idea there was an Occupy Gaddis reading of “JR” during the height of the Occupy movement, which Mr. Tabbi cites here.) The biographer cleverly quotes Mitt Romney’s campaign statement that “corporations are people too, my friend,” which almost sounds more like Gaddis doing Romney than Romney himself.

Mr. Tabbi won’t make any friends, however, with his continued insistence that Gaddis’s books are not difficult. Gaddis’s novels are written almost entirely in dialogue without any designation of who is speaking, are rich in obscure symbolism, allusions to myth, and the history of classical music; and while it’s true that a continued immersion in his work results in an acquired fluidity for the reader, it seems nearly a provocation to hear Mr. Tabbi state so categorically that “there is no serious argumentative support for the ‘difficulty’ claim.” (Readers like John Gardner and Jonathan Franzen beg to differ, by the way.)

Mr. Tabbi tries to explain away the charge of Gaddis’s difficulty this way: “as a visceral reaction to a work that so elicits a reader’s participation to the point of becoming a collaborator, or co-creator.” A statement that, to most readers, sounds like the very definition of “difficult.”

I doubt if even Gaddis’s most earnest champions (like myself) would deny that the picking up of one of his novels is a demanding, and even an occasionally maddening, experience. No writer as ambitious, important, or richly rewarding could be anything less. We were lucky to have him, and the only shame of it is that with Gaddis’s death in 1998 we were robbed of his take on Internet culture (with which he would have undoubtedly had a field day).

No matter how he tries to mitigate it, Mr. Tabbi has taken on a difficult subject and mostly triumphed: His book is the best (so far) in understanding this underappreciated titan of American literature.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of the novels “Lit Life,” “Gotham Tragic,” and “Exposure.” He lives in Springs.

William Gaddis spent summers in Wainscott for many years and owned a house in East Hampton from 1995 until his death.