The Musician as Alchemist

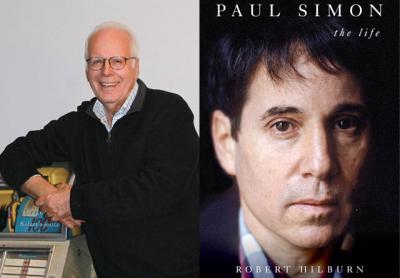

“Paul Simon: The Life”

Robert Hilburn

Simon & Schuster, $30

I can still clearly recall the silence maintained by all 10,000 of us, in rapt attention under a late-afternoon sun at Indian Field Ranch in Montauk, all eyes on Paul Simon and the South African vocal group Ladysmith Black Mambazo as they sang the transcendent, a cappella “Homeless” from Mr. Simon’s 1986 hit album, “Graceland.”

That memorable moment, in late August 1990, was one of so many, as the artist and his band, many of them Africans, repeatedly brought the audience to ecstasy, as with spirited renditions of the triumphant “You Can Call Me Al” and “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” also from “Graceland.” Billy Joel stopped by, too, drawing cheers at the mention of Montauk in “The Downeaster Alexa,” his song about beleaguered baymen.

It was easy to feel that we were witnessing a rare and exceptional moment. Paul Simon, a prolific author of a quarter-century’s worth of hit songs, and now a resident of our still-sleepy hamlet, had added alchemist to his résumé, and before our eyes was somehow blending the doo-wop and pop of his New York City youth with the faraway sounds of the Zulus, creating an entirely new vibration that had a most magical power. You really should have been there.

It was a moment of jubilation, but for Mr. Simon, who, at 76, has recently embarked on “Homeward Bound — The Farewell Tour,” only one of too many to count. Of course, behind the massive success lies a man susceptible to the flaws and foibles of his species; failures, be they artistic, commercial, or personal, have sometimes accompanied that success.

A thorough portrait of the artist is found in “Paul Simon: The Life” by Robert Hilburn, who has penned biographies of Johnny Cash and Bruce Springsteen, as well as “Corn Flakes With John Lennon and Other Tales From a Rock ’n’ Roll Life.”

If not quite hagiography — literally, the biography of a saint — Mr. Hilburn clearly sees “The Rhythm of the Saints,” Mr. Simon’s 1990 follow-up to “Graceland,” and almost all the rest of his subject’s oeuvre as works of staggering genius. But whatever one thinks of Mr. Simon’s music, be it the iconic 1960s output with Art Garfunkel, his 1970s catalog with hits like “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard,” “Mother and Child Reunion,” and “Still Crazy After All These Years,” or the last three decades’ exploration and incorporation of sounds and rhythms from around the globe, his impact on popular and world music is indeed staggering.

He was born in Newark in 1941, but fate soon took young Paul Simon to Queens, where he first remembered seeing Mr. Garfunkel, in 1951, at P.S. 164. The fourth graders were at an assembly, where Mr. Garfunkel sang “Too Young,” which had been a hit for Nat King Cole. Though baseball was his obsession, two things struck him, Mr. Hilburn writes: “The loveliness of Art’s voice and the strong impression he had on the girls.”

Soon after, Elvis Presley and, particularly, the Everly Brothers showed the young duo the way forward; as teens they scored a few minor hits under the name Tom & Jerry. But Mr. Simon’s decision to record a couple of songs on his own, not instead of but in addition to another Tom & Jerry record, was a stinging betrayal, as Mr. Garfunkel saw it. The wound would come to define the singers’ relationship forevermore.

Mr. Hilburn chronicles Mr. Simon’s years in England, where he found some success and lifelong friends, before a return to New York and the fast upward trajectory of Simon and Garfunkel. But Mort Lewis, their manager, saw the rivalry beneath their friendship, Mr. Hilburn writes. “Paul often thought the audience saw Artie as the star because he was the featured singer. . . . Meanwhile, Artie knew Paul wrote the songs and thus controlled the future of the pair. I don’t think he ever got over what happened with Tom & Jerry.”

When Mr. Simon feared that Mr. Garfunkel was moving toward an acting career and would have quit the duo should it prove successful, he ended the partnership, infuriating Mr. Garfunkel. “The relationship was too restrictive,” Mr. Hilburn writes. “Simon wanted the freedom to move beyond the mostly soothing folk strains that lifted Simon and Garfunkel to superstar status in rock. He heard a whole new world of music in his head, and he wanted to pursue it.”

The split allowed Mr. Simon’s artistry, for which experimentation was crucial, to fully blossom, and the hits began straightaway with his self-titled solo debut in 1972, continuing through the following year’s “There Goes Rhymin’ Simon” and 1975’s “Still Crazy After All These Years.” A friendship with Lorne Michaels, the creator of “Saturday Night Live,” developed around the same time and also yielded decades’ worth of successful television appearances.

But amid the peaks, valleys would lie. “One Trick Pony,” the 1980 film that he wrote and starred in, was poorly received, and while its soundtrack album featured the hit “Late in the Evening,” it was his first to fall short of the Top 5 in the United States. With MTV and a new crop of pop stars ascendant, the 1983 album “Hearts and Bones” was another disappointment. (“The Capeman,” a musical play based on the life of a convicted murderer that Mr. Simon co-wrote with the late poet and playwright Derek Walcott, was savaged upon its short run in 1998.)

Around the time of “Hearts and Bones,” Mr. Simon’s second, brief marriage, to the actress Carrie Fisher, also ended, and the depression that has sometimes afflicted him reared anew. “He felt numb some days,” Mr. Hilburn writes, “able to think of nothing better to do than sit in his car and idly watch workmen build a house that he had planned for Carrie and himself in Montauk. . . . At the construction site, Paul would often smoke a joint (which he had picked up again after an eleven-year break) and listen to tapes, choosing them pretty much at random — until he noticed one day that he had been playing a particular tape of South African music over and over.”

Thus began a personal and professional resurrection, albeit one that brought its own controversies. Mr. Hilburn amply covers charges that Mr. Simon was breaking a boycott of South Africa, then in the late, violent stages of apartheid, and engaging in cultural appropriation. Opinion remains divided on both topics, but “Graceland” surely marked a transformation in Mr. Simon’s approach to music. Instead of sweet folk harmonies over an acoustic guitar, he was constructing songs with sounds sampled from around the world, and leading large groups of equally disparate musicians onstage.

The fitful reunions of Simon and Garfunkel are detailed, and this aspect of Mr. Simon’s career has a less happy ending than the entirety of it. For Mr. Garfunkel, though, it’s quite a bit worse. The onetime team is apparently not on speaking terms, following a 2010 tour that was marred by vocal problems Mr. Garfunkel developed shortly before it began.

In the end, Mr. Simon is a songwriter and musician, and while the Rolling Stones may not have recorded an essential album in decades, who are we to tell them to stop? They, like Bob Dylan and Paul McCartney, are among the iconic artists of the 1960s who continue to perform well into their 70s, and fans continue to buy tickets.

For his part, Mr. Simon, who found domestic bliss with the singer Edie Brickell, with whom he has three children, has continued at his own pace, scoring a minor hit with “Wristband” from 2016’s “Stranger to Stranger,” and sharing honors with Dion on the earnest 2015 duet “New York Is My Home.”

A London date on his 2016 tour coincided with the American presidential election. “The election put a pall on everything,” Mr. Hilburn quotes his subject saying, “looking exhausted as he sat in a chair. . . . With a word change here or there, the road-weary lyrics of ‘Homeward Bound’ applied again.”

But, Mr. Hilburn writes, Mr. Simon brightened as he saw one era of his life ending and another beginning. “He now planned to go to Hawaii with Edie and the kids for a monthlong vacation and try to figure out if he could really walk away. Whatever, he felt blessed. Only three months ago, he and Edie had renewed their vows overlooking the ocean at their home in Montauk.”