Mysteries and Connections In Artist’s Montauk Works

Heinz Emil Salloch has the kind of unlikely story one does not encounter every day. He was a refugee from Nazi Germany because he refused to join the National Socialist Party and continued to teach art to Jewish children. He fled the country in 1937 to Cuba first, then to the United States, where he found his way from Florida to New York, then to the South Fork, and finally Montauk in 1938. He died in 1985.

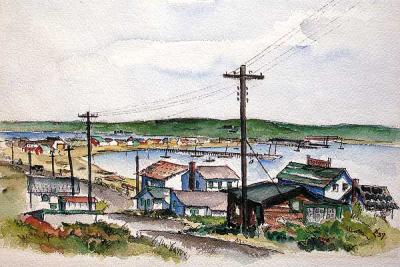

Given the well-documented lore collected on the exploits and backgrounds of notable artists who visited this area over the past century or so, it is extraordinary to discover a new artist who made the trek out here, especially in the large gap that exists between the 19th-century painters and the mid-20th-century Moderns. What is particularly striking about his watercolors of sites such as Ditch Plain, Fort Pond Bay, Culloden Point, and the old Montauk Village, is not just how much has changed or not, but the expressive realist style, still prevalent in both Europe and even America at the time he chose to paint these subjects.

With the Abstract Expressionists not due to arrive for another decade or so, Salloch captured Montauk in a style we are not accustomed to seeing. As a result, the strong linear focus of the work and the artist’s sharp use of shape and color seems remarkably fresh.

What is even more intriguing about the enterprise is that it comes with a bit of mystery. By the titles he gave his works, Salloch was often very detailed in locating his subjects. When he did not include a specific place name with a painting, one has to wonder where he might have been. Karen Dorothee Peters, a curator from Germany who now lives in New York, was introduced to the work by the artist’s son, Roger Salloch, and has since set about cataloging the paintings, locating those unknown subjects, and comparing the known ones to how they look today.

In a recent visit to Montauk, Ms. Peters met up with Dick White, a historian and member of the Montauk Point Lighthouse committee, and Brian Pope, the assistant site manager at the Montauk Historical Society, who helped show her the sites that were notated and others that might be among those unknown. It was a bit of an art detective mission in the bright clear light of a Montauk spring day.

There were several complications stemming from both man-made and natural forces. Salloch was painting here both before and after the Hurricane of 1938. He was also painting before Montauk Village moved from the Navy Road area to its present location. Heavy brush overgrowth has made some of the obvious vantage points inaccessible by foot today.

In the early part of the day, the men took Ms. Peters to a hill overlooking Rocky Point and Culloden Point in the distance to show her where one painting might have been executed. For a painting titled “South Shore,” they went to the Lighthouse “and compared the shoreline, thinking it might have been done from the ledge; and then to Camp Hero as a surfer suggested it was made there,” she said.

For a painting titled “Montauk Village,” from July of 1939, she was taken to a spot just up the hill from Duryea’s Lobster Deck, which, despite the fact that the village the painting refers to no longer exists and is replaced by condominiums, is indisputably the right spot.

For a scene titled “The Old Windmill,” they went to Ditch Plain, but couldn’t really make out from exactly where it might have been painted. They ran into Jim Grimes, “who told us that his grandparents were caretakers of the windmill and his father was born in it.” They continued to debate it.

The exact locations depicted in many of the works continue to be a mystery. A watercolor titled “Fishing Dock” appears to have been done around the present Gosman’s complex, but where exactly in the current configuration of buildings was difficult to determine.

Still, the trip opened up a dialogue that Ms. Peters hopes will only continue in the future. (In addition to the images here, a slide show on The Star’s Web site and a link to her Facebook page will allow readers to share their own insights as to where a particular painting might have been executed.) She is in discussions with several venues to show the work on the South Fork in the near future.

The artist’s son, who is a friend, asked Ms. Peters to help settle the German part of his estate some six years ago. “When I discovered the shoreline pieces, it became a second trip for me here. I was just arriving freshly from Europe and rediscovering the area, but knew these paintings had to go back to where they were made. No one else would appreciate them more.”

A French film company has just acquired the rights to the story of how the the younger Mr. Salloch took his father’s paintings back to a German audience.

The works Ms. Peters has been studying were part of a large storage area that had been mostly untouched during the artist’s lifetime and after his death. Each new discovery was a very exciting process for her. In all, the artist painted 30 Long Island works.

Ms. Peters said that in Germany his style had been more traditionally expressionist. “The German watercolors have less of a documentary quality. . . . When he came here he became an acute and keen observer of detail in an effort to understand his new environment.”

“That he was very introverted shows in his work,” she said. “He’s very intimate with what he sees. Mostly he paints with a focus on landscapes and seascapes, barely portraying people.” With their particularly frank 1930s style and the simplicity they depict, she said, “You may be able to see the old American dream in these paintings. For me they are very soulful connectors with land and identity.”

Please click on link to see some of these paintings.

http://www.easthamptonstar.com/Salloch_slideshow

or http://kdpprojects.blogspot.com to leave comments on locations.