Nature Notes: Rock Solid

The major question having to do with climate change before the East Hampton Town Board today is how do we save Montauk from global warming. Do we continue to pump a million bucks into beach nourishment each year, do we move Montauk up the hill as suggested by the latest hamlet study, do we do nothing and let Montauk sink beneath the slowly elevating surrounding seas?

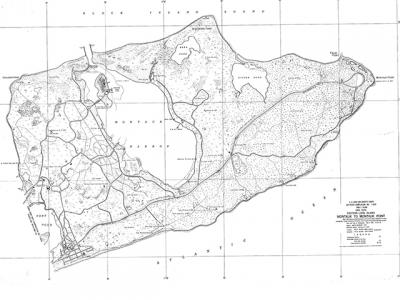

We are told that George Washington made a special trip to the end of Long Island to see where the lighthouse, the fourth oldest in the country, should be built. What he saw when he reached Montauk Point was a big bump some 50 to 60 feet high and a long low point of 200 or so feet extending out into the ocean at the foot of the bump. George was no dummy. Before leading America to victory against the British in the Revolutionary War, he had been a surveyor and had traveled throughout much of the eastern and central United States drawing maps of the terrain and the area it covered. He is said to have pointed to the top of the bump and said (or wrote), “Put it there!”

In 1796 work got underway, a company was hired, and a lighthouse was built, its foundation eight feet or so into the soil with walls six or seven feet thick. When it was finished its octagonal tower built of sandstone from elsewhere reached 110 feet above the bump. Voilà! Long Island had its first lighthouse and it has stood there ever since.

Come the 1970s when the U.S. Coast Guard, the lighthouse’s owner as was traditional in those days on both American coasts, began wondering what to do. Tropical storms and northeasters had done away with that long point and were beginning to seriously erode the bump itself. Along came a painter by the name of Georgina Reed from the middle of the Island and saved the lighthouse by terracing the outer wall of the bump and in such a way that water no longer flushed down the sides of the bump, abetting erosion from above and using phragmites stalks and the like to keep the water dripping down rather than running down. Big rocks were then brought in and placed at the bottom of the terraced slope and erosion was greatly reduced. The lighthouse was saved.

A young Irishman who was very interested in the ongoing interaction between the sea and the land came along to observe, joined Georgina, and stayed until the job was completed and the lighthouse saved for another 50 years or so. That young Irishman, Greg Donahue, has never left the lighthouse’s side since and is still the National Landmark’s chief protector today. There are no George Washingtons today, no Georgina Reeds, but, thank God, Greg the Irishman is still going strong and still saving structures from erosional forces right and left using the fine art of terracing along with proper large stone placement where the side of a bluff meets the beach.

Not far away, there is a large house built early in the 20th century that some call the Stonehouse planted behind the Montauk ocean bluff that was about

to fall into the ocean. The East Hampton Town Zoning Board of Appeals

reluctantly gave a permit to its owner, and another Montauker, Keith Grimes, trucked in large rocks and placed them at the base along the entire extent of the property owner’s bluff. They were not properly fitted, but nevertheless, the bluff lasted long enough until Greg came along and terraced it in the fashion of the lighthouse terraces and brought in more rocks. There is a problem, however. The bluff on the lighthouse side of the property is being eaten away and apparently the owner is not taking steps to protect against these serious inroads.

The Montauk ocean bluffs are the last you will find all the way into the city, except for some on Staten Island, and down the coast to Virginia. They are an integral part of Montauk’s coast and only give into the sea grudgingly. On their tippy tops grow an interesting collection of plants, some federally endangered like the sandplain gerardia, several orchids, and a few salt marsh plants growing out of character. Behind these bluffs are holly and shad heathlands and among them a variety of small ponds with some rare aquatic plants edged with violets as well as blue-spotted salamanders, eastern newts, spadefoot toads and several other amphibians and reptiles. Colonial brown and white bank swallows drill into the outer face of these bluffs to lay eggs and raise young, while an occasional kingfisher joins the crowd to occupy a much larger hole among them.

Back to the “retreat or stand your ground” moment, down-to-earth Montaukers love their land and the waters it meets and don’t buy the idea of a retreat from rising seas. As a result of a northeaster that hit Montauk in 2003, John Ryan, at that end of Surfside Drive where it meets Shadmoor State Park, lost part of his house and a large hunk of his land. He was allowed to rebuild, but erosion keeps eating at the Surfside bluffs between his parcel and downtown Montauk. Recent erosion caused by waters from a stream draining to the ocean from Shadmoor has been removing more land. He’s been there for more than 50 years. What is he to do? [Editor’s note: Larry Penny worked as an environmental consultant for Mr. Ryan when he appeared before the town zoning board in 2014 requesting permission to build a 185-foot-long stone revetment at the bottom of the bluff in front of his house.]

Around the turn of the century there was a hue and cry to move the lighthouse. In the 1990s the famous lighthouse on Cape Hatteras, which was built on dunes, not on hard land, was moved more than a half-mile back from the ocean and that engendered a lot

of “move-the-lighthouse” cries from groups not only on the Atlantic Coast but on the Pacific Coast, as well. George Larsen ran the Montauk state parks at that time and the lighthouse had by then changed hands from the Coast Guard to the Montauk Historical Society.

George and others interested in keeping the lighthouse as is came to the conclusion that that lighthouse could be saved in situ and set about devising a plan to do just that. But the group needed someone who knew the ins and outs of saving large structures from the mercy of the waves. They turned to Greg Donahue.

Wheels began to turn, the Army Corps of Engineers carried out a large feasibility study and impact statement that inched its way through several reviews and, finally, Greg was brought on to lead the way. Money slowly came through and Greg and his team were in business. After squabbles and debate, the town finally let them use the road to Turtle Cove as a way down to the base of the bump on which the lighthouse stands. Greg knew in his heart that much more work would be needed in the future but he went ahead anyway and made the best of it, and the lighthouse lasted for another 16 years or so.

In 2012 the lighthouse was given National Landmark status. Having shown that terracing and rock revetments can be an effective means of keeping the ocean at bay, the lighthouse project has received a substantial amount of money, as much as $24 million, for the construction of a new rock revetment. The work could begin as early as the fall of this year.

Why have I spent so much of your time talking about the lighthouse and efforts to stem erosion in Montauk and elsewhere? Because I believe strongly that it would be a giant waste of money to turn downtown Montauk into uptown Montauk, that a revetment, such as those that have saved the Montauk Shores Condominium cluster from washing away (and that by the way had the blessing of former Supervisor Tony Bullock, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, and yours truly), could be placed in front of the row of hotels, motels, whatever, in downtown Montauk to keep downtown Montauk downtown! Where would the Netherlands, one of Europe’s oldest and most prosperous countries, be today if it retreated when it began to be overrun by flood tides?

We have seen how large sand bags have not been able to withstand the ocean’s forces. We have watched a sand dune west of hotel-motel-condominium row that existed for a hundred years or more be leveled in a few days in order to provide beach nourishment for that same hotel-motel-condominium row. We have seen how the Town of East Hampton, Suffolk County, and our state national governments have frittered away millions on half-baked plans that were faultily executed. We should no longer put up with such doings. You need a skilled and seasoned contractor, one who knows the vagaries of winter storms and summer hurricanes as well as the secrets of saving land and structures from coastal flooding and unrelenting surfs. I think you know of whom I am speaking.