Not-So-Bitter Brew

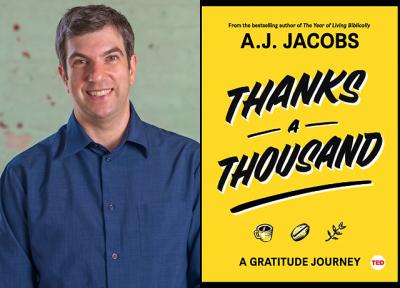

“Thanks a Thousand”

A.J. Jacobs

TED Books, $16.99

Ah, coffee. Chromosome crackler. Goose to flagging spirits. Drudgery obliterator. Focus for the brain’s fog. Fuel to modernity’s engine. Where would we be without it?

In this caffeinated society, if you’re going to be grateful for something, King Bean is hard to beat. A.J. Jacobs wasted no time in seizing on this when he set about looking for a “mental makeover” and his next writing project. As a middle-aged parent of young boys, he admirably sought to spend less of his remaining time on earth annoyed and irritable, anxious, hidebound by the “deficit” mind-set, as the academics call it — that is, dwelling on the negative.

Thus Project Gratitude, as articulated in his latest book, “Thanks a Thousand,” the thousand referring to the number of people he aims to thank for the work they put in toward his getting his mitts on his paper cup of morning coffee, “something I can’t live without” — even if they’re as indirectly involved as a maker of wooden pallets.

It’s “a huge theme I’ve noticed in my previous writing projects,” Mr. Jacobs says. “That the exterior shapes the interior. That our speech and actions change our thoughts.”

And so the annoyed man becomes the annoying. He does not stint on the thank-you notes — “most of the people don’t write back” — or the ingratiating phone calls. About that pallet manufacturer, Mr. Jacobs gets the boss on the horn from New Jersey and hears falsely effusive thanks for his thanks. Undaunted, he follows up later with a legitimate question and is practically hung up on.

“Well, that’s fine” is how a deputy commissioner with the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene answers what must have sounded like a prank call but in reality was an expression of gratitude “for keeping my food safe.” Here and elsewhere, the reader helplessly pictures eyes rolling skyward in disbelief, shoulders slumping with exasperation, mouths going slack with contempt.

At a Brooklyn coffee roastery, he attempts to thank a guy on a forklift and is waved off. “Maybe he thinks it’s condescending to be thanked. Maybe he just wants to be left alone to do his job. Maybe the other guys do as well but are too polite to say so.”

One appreciates the author’s honesty.

Some of the parties involved don’t deserve thanks at all. The inventors of the Java Jacket may have had a sample of their brainchild in an exhibition called “Humble Masterpieces” at the Museum of Modern Art, but what an extraneous, resource-wasting scourge that paper sleeve is.

Again to the author’s credit, by the end of his tale he shows up at his favorite neighborhood coffee shop with a reusable container in hand.

When his attention turns to coffee lids and a chapter subheading reads “Thanks for Stopping the Coffee From Spilling on My Lap,” it brings up a curious omission: the infamous and tort-rattling lawsuit over just such a scalding in the early 1990s, which was widely condemned as frivolous but in fact wasn’t, given the 79-year-old female plaintiff’s reddened and blistered private parts and subsequent skin grafts and the necessary punitive judgment against the Golden Arches.

Unscientifically speaking, this reader has often gratefully thought of that case and its moderating influence on the industrywide practice of sadistically serving up to-go coffee so hot it could have been fresh from the Fukushima reactor.

The thanks are a gimmick. And maybe that’s okay. But is this a book about gratitude, or is it a book about coffee? In a New York Times piece about serial memoirists last week, Mr. Jacobs was referred to in passing as a “stunt” journalist like George Plimpton, a practice that may have made more sense in the past with books like “The Year of Living Biblically,” but here, why not just write about the history of the potent drink, something like Mark Kurlansky’s “Salt”?

Even as a vehicle to compassion and storytelling, the psychological implications of forced gratitude can’t compete with, for instance, the description of an arduous trip to a small coffee farm in remote Colombia, during which from the back of a pickup truck the author catches the driver making the sign of the cross as they skirt a rocky cliff-side road.

Mr. Jacobs rightly worries about being condescending. He’s not alone. Still, it has to be said that the sincerity is endearing when after a dinner he’s sitting on the farmhouse porch, looking out over the mountains and greenery, the source of it all, as it were, and pulls out a crumpled note of thanks for the family’s hard work.

He reads in halting Spanish of how happy and energized their crop makes him back in the United States. He won’t take it for granted, he says. “From now on, I’ll think of you when I drink my morning coffee.”

You want to believe him.

A.J. Jacobs has family in East Hampton.