Not-So-Little Murders

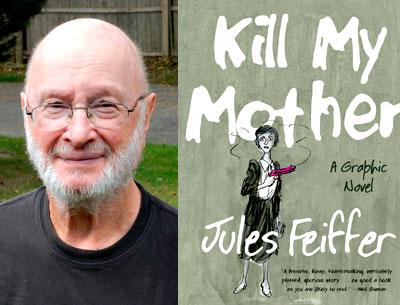

“Kill My Mother”

Jules Feiffer

Liveright Publishing, $27.95

As I eagerly devoured “Kill My Mother,” Jules Feiffer’s brilliantly funny, moving (both emotionally and visually), multilayered film noir homage, I kept thinking this graphic novel could easily transfer to the screen — as an animated film. Hell, it already is an animated film on paper.

Every page in “Kill My Mother” is alive with movement, or what animators call “extreme poses”; that is, storytelling facial and bodily expressions that visually communicate the narrative to an audience.

Mr. Feiffer’s well-known love of the elegant art of Fred Astaire shines throughout. His cartoon characters literally leap and dance off the page, as they continually run into and out of danger. Or a woman sings an improvised lullaby while lifting a boy into the air, twirling in multiple sequential poses reminiscent of the “modern dancer” often seen in Mr. Feiffer’s long-running Pulitzer Prize-winning Village Voice comic strip. Or a drunken over-the-hill private eye slugs a guy in the face with a pistol in a frozen apache dance moment.

The first appearance of a cocky boxer named Eddie Longo, also known as “The Dancing Master,” offers a veritable showcase of Feiffer “moves” — precise frame-by-frame fight poses resembling a beefcake pas de deux.

Mr. Feiffer knows the animation medium well; he won an Oscar in 1961 for the biting anti-authoritarian animated short “Munro.” In “Kill My Mother” he’s done all the hard groundwork for a future adaptation to a cartoon film. The story and dialogue (taut and gripping) are accompanied by expressionistic storyboards of sequential imagery filled with famed noir tropes and directorial touches.

The characters — all of them by turns menacing, seductive, driven, violent, vindictive, hard-boiled, pathetic — elicit from readers a sympathy or, at least, recognition of the human condition through Mr. Feiffer’s empathetic drawings. His loose draftsmanship may appear improvisational — and at one point in the creative process it no doubt was — but what ends up on the page is highly selective. Mr. Feiffer’s intelligent and artistic presentation hits all the emotional buttons of his characters. Mr. Feiffer obviously does thorough research and I assume creates many drawings in order to make the strongest graphic statements he can make, choices that are calculated to get an audience to respond emotionally.

The layout of the sepia-colored pages is extraordinarily cinematic in ways that Orson Welles might have approved (and maybe envied). The first chapter opening — two teens jitterbugging in a 1933 San Francisco apartment — is in the old square 1.33 screen aspect ratio, which Mr. Feiffer immediately breaks out of. Depending on the needs of the story, his geometric panels constantly change shape — stretching to Cinemascope proportions, overlapping, blurring, and sometimes they disappear altogether, emulating spot-on uses of the close-up, camera pans, subjective shots, over-the-shoulder shots, subjective point of view, cross-dissolves, and so on.

The influence of Mr. Feiffer’s early mentor Will Eisner is surely felt (as is the lesser-known but brilliant innovator Harvey Kurtzman), but Mr. Feiffer goes further than any other graphic novelist in creatively melding his phenomenal success as a stage and screen writer and print and film artist.

The page layouts for a steamy jungle mise-en-scène on a war-torn Pacific island are particularly impressive. Five panel frames are placed within surrounding, suffocating dense vegetation — vines, roots, leaves, and palm fronds that spill over the panels and to the edge of the page. Mr. Feiffer’s visualization makes the reader feel as ensnared, claustrophobic, and panicked as the character desperately seeking escape from her tropical hell.

Animation is not a genre. It is a method of storytelling, as Brad Bird (director of “The Incredibles”) once said. It is a technique, a tool that can do western films, science fiction, horror, screwball comedies, and film noir and other genres. But in America, animated features are ghettoized in the children’s film category. Perhaps “Kill My Mother” will attract a brave producer who will use its sensibility, humor, sarcasm, murder, and sex to move U.S. animated features toward a new adult audience and a new entertainment level.

Meantime, buy Mr. Feiffer’s book. If you don’t, “. . . you’ll regret it. Maybe not today. Maybe not tomorrow, but soon and for the rest of your life.”

John Canemaker is an Oscar-winning animation filmmaker, a tenured N.Y.U. Tisch School of the Arts professor of animation, and author of 12 books on animation history, including “The Lost Notebook: Herman Schultheis and the Secrets of Walt Disney’s Movie Magic.” He lives in New York and Bridgehampton.

Jules Feiffer lives in East Hampton.