Occupation? What Occupation?

“A Hero of France”

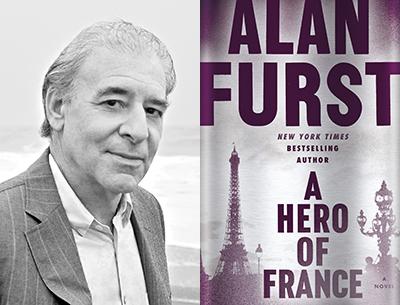

Alan Furst

Random House, $27

Of contemporary spy novelists, Alan Furst is the undisputed king of historical espionage. The majority of his 14 novels are set in Europe during the 1930s and ’40s, dealing primarily with the machinations of resistance fighters and spies — with a love affair or two thrown in for good measure. At their best they are atmospheric and suspenseful, occasionally lyrical, and often infused with a dash of erotic heat; Mr. Furst is the rare contemporary novelist who writes well about sexuality.

This is at least partially due to the time period; sex circa World War II is much less tricky than what faces the novelist working in a contemporary setting, where one must navigate a complicated postfeminist universe. Nevertheless, Mr. Furst seems to have a genuine Updikean eye for naughtiness.

You get a little taste of this right away in Mr. Furst’s new novel, “A Hero of France,” which takes place in Paris in 1941 during the German occupation. In an early scene, Mathieu, a French Resistance fighter, slips into a seedy nightclub to meet with the owner, Max de Lyon, who wants to aid the cause. And wouldn’t you know it? During the meeting a can-can audition is taking place where a bevy of young women in bra and panties are trying to impress a randy stage director. Who will be the lucky girl? De Lyon already knows: “The one on the left with the big behind — the German soldiers are partial to big behinds.” After a visit to the men’s room with the director, her job is secured. C’est la vie.

The nightclub scene may remind some readers of Eric Ambler, the 20th-century English novelist whose spies always seemed to find the most squalid bars and boites to do their business. Though they are often mentioned as literary cousins, Mr. Furst doesn’t have Ambler’s knack for lurid nostalgia, nor do Mr. Furst’s characters have the psychological complexity of those of other thriller writers such as Graham Greene or John le Carré, to whom he is also compared.

What Mr. Furst does have is a deceptively breezy prose style to go along with propulsive storytelling instincts that make his books eminently readable. “A Hero of France” is no exception. In this panoramic, if slight, tale of the French Resistance, sentences fly by with the greatest ease; you suddenly awake from your reverie to find that you’ve knocked back 50 pages when you’d thought you’d read 20. This, I would argue, is the foundation of Mr. Furst’s success, something akin to the dancers of de Lyon’s nightclub: He gives pleasure.

At the same time, “A Hero of France” is disparate and episodic. The beginning of the novel mostly follows Mathieu as he helps downed British airmen escape into Spain, and with the introduction of Major Broehm — a German intelligence officer determined to crush this part of the Resistance — you think the novel is set up for a matching of wits culminating in a grand showdown. But Mr. Furst can’t stop adding characters — an old lover of Mathieu’s, a restaurant owner, a nerdy Nazi sympathizer, a determined German civil servant, a teenage Resistance fighter — all of whom begin plotlines of their own, some of which are loosely developed, others that go nowhere. In the midst of this muddle, we lose track of Mathieu, and the narrative backbone goes limp.

There are lively scenes, of course, such as when Mathieu and his team commandeer a butcher’s truck to transport more downed airmen and end up in a firefight with a German patrol. There’s more erotica too, as when the wife of a wealthy member of the Resistance sunbathes nude as an invitation to either Mathieu or his female counterpart — though more likely both. (Sadly for the reader, she is to be disappointed.)

At a certain point, though, you may begin to wonder if anything is really at stake in “A Hero of France.” Yes, there are arrests in the novel, serious wounds, and even death. But over all things go pretty rosy for these Resistance fighters. Even Broehm himself seems innocuous; instead of brutal interrogation, this commandant practices a technique of reason and subtle pressure with his prisoners that seems out of step with what is generally understood about Nazi methods. Certainly it is out of step with creating fictional tension and urgency. In this novel, the only power Broehm wields with his captured prisoners is the power of suggestion.

The ending is a flurry of quick summaries as the author tries to tie up all his threads into neat little bows. Some of the vignettes are amusing; others are so cursory you won’t much care (you never really knew the character anyway). As the novel ended I couldn’t help think of Ernest Hemingway’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls”: There too you have a hero taking on Fascists as a Resistance fighter, but everything is played for much higher stakes, and the famous ending to Hemingway’s novel is one you never forget.

“A Hero of France,” on the other hand — while a fitting tribute to the brave women and men of the Resistance — forgets a major edict of drama: There’s no true heroism without tragedy.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of the novels “Lit Life,” “Gotham Tragic,” and “Exposure.” He lives in Springs.

Alan Furst lives in Sag Harbor. “A Hero of France” comes out on Tuesday.