‘Oh, Fearsome Land’

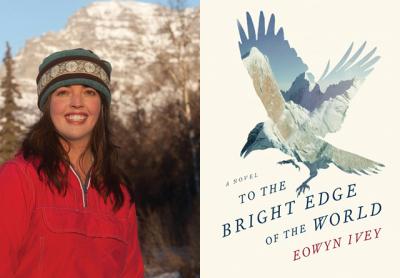

“To the Bright Edge of the World”

Eowyn Ivey

Little, Brown, $26

You know an author has successfully taken you on a vast journey when toward the end of 400-plus pages, through meager meals of moldy salmon, stringy rabbit, or bug-infested rice ingested by haggard explorers on foot in the Alaskan wilds, at last they are given a breakfast of fresh coffee and hardtack at a depleted trading post and you can almost taste it yourself.

Two days later — as recorded in the journal of Lt. Col. Allen Forrester of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, leader of an expedition to map the territory’s interior and document the native tribes there — the nourishment comes by way of an abandoned wife of a missionary of the Moravian Church who serves Forrester and his ragtag crew “our first real meal in four months, including fried eggs, bread, potatoes, & turnips, all sprinkled with generous amounts of salt.” A return to civilization, you might say, along the western Yukon River in July of 1885.

Eowyn Ivey’s second novel, “To the Bright Edge of the World,” is at once an adventure tale shot through with a kind of magical realism involving tribal spirits of the dead resistant to the white man’s incursions and a black-hatted shaman who takes the form of a trickster raven, an epistolary love story, an ode to North America’s last wilderness, and an affectionate rendering of the bird life of the Great Northwest. In it, Forrester’s crew is Lt. Andrew Pruitt, intense and of a scientific bent, a reader of the poems of William Blake charged with recording weather conditions and taking photographs, Sgt. Bradley Tillman, in some ways Pruitt’s opposite, impulsive and well built, Nat’aaggi, a native woman who married a man she says could turn into an otter only to skin him and don the pelt after he mistreated her, and a half-wolf, half-dog Tillman names Boyo.

In the telling, Forrester’s journal is answered by that of his wife, Sophie, an inveterate birder left behind in the Vancouver Barracks of the Washington Territory, where she channels her loneliness and loss into the fledgling art of photography. What’s more, the reader gets to see at least one example of her work, as the book is a creative hodgepodge of photos both new and archival, color and black and white, along with 19th-century advertisements and lithographs; sketches of landscapes, artifacts, and animal tracks; faux newspaper articles that flesh out the story; passages and diagrams from vintage medical books; wall text for a historical society exhibit about the Forrester expedition, and contemporary letters between its curator and the Forrester descendant who supplies the items to go on display.

It’s such that you never know what might appear on the next page.

For the armchair traveler fascinated by Alaska, which, remote, “other,” and resource-rich, remains something like a colony even today, the letters of Josh, the curator, who is of mixed native and European descent, to Walt, Allen Forrester’s great-nephew, are particularly enlightening, capturing as they do some of the cultural realities of the place — the tribal members committed to their work with the exploration and extraction companies, for instance, or the elder who thought the old ways “backward and evil,” and so on to the sense that, as Josh puts it, “when we use terms like subjugation and loss and the desire to ‘preserve culture,’ it devalues and limits people in a way that I don’t think is accurate.”

It’s complicated, in other words. He also, by the way, in what is at times a rather meta running commentary on the fictional journal entries we read, offhandedly gets across a few of the indelible smaller charms of life in the interior, like the way those brainy ravens will rifle any grocery or garbage bag foolishly left in the bed of a pickup.

Eowyn Ivey will take part in the East Hampton Library’s Authors Night book signing, sale, and fund-raiser on Aug. 13 at 5 p.m. She lives in Alaska with her husband and two daughters.

Baylis Greene lived in Fairbanks, Alaska, from 1994 to 1999.