Opinion: A Brilliant ‘Brilliant Divorce’

It is a sad fact that as an actress matures and ages, the parts available for her decrease. She may be getting wiser and better as a performer, but the characters to show it simply aren’t there. Theater, while an art form in which women can thrive, has historically been male-dominated, hence the dearth of mature female roles.

So it is wonderfully refreshing to see a play like the comedy “My Brilliant Divorce,” a one-woman show starring Polly Draper as Angela, that made its debut on Saturday at the Bay Street Theatre in Sag Harbor. This is an Americanized version of the Irish writer Geraldine Aron’s play, which has run for years in Dublin and London — Americanized in that Angela is written here as an American living in England.

Angela is facing a true midlife crisis. Her English husband has left her for a younger, large-breasted woman and her daughter has left home with a drummer, leaving behind an empty house and a dog named Dexter. Alone, Angela wrestles with her demons: her sense of inadequacy and self-loathing, her love-hate relationship with her ex-husband, and her own repressed sexuality and desire.

The talented Ms. Draper, best known for her work in the TV series “thirtysomething,” is now fifty-something, and is well placed, temperament-wise, in the part. She has the sense of fun and at the same time the vulnerability to play Angela.

There are, however, challenges for her in this production. For one, on opening night, she suffered a bit of vocal distress, with a scratchy throat and a slight cough. Ms. Draper is not one to get thrown off onstage, and she battled through, but her performance seemed sometimes tentative, particularly in the first act. More of that later.

Ms. Draper is a wonderfully playful, inventive performer, and when she did bite into her role Saturday, the results were special.

One of the highlights of the show comes quite early, as she wrestles with the reality that her husband has left her. “I made up my mind to see his departure as a reprieve,” she says, and begins listing all the things about him that she hates. The loathing that oozes out of Ms. Draper’s Angela — the kind that can only come from being in a long, sustained relationship — is truly side-splitting.

Her trip to a sex shop to buy a vibrator, on the advice of her doctor, is another highlight of the hour-long first act. Ms. Draper’s recounting of her conversation with the clerk, whom she imitates, speaking in a thick Cockney accent, is hilarious, as is her trip back home with her shopping bag containing the new toy. It is rare in a review to mention the prop designer, but Kathy Fabian’s sex-shop shopping bag was brilliant.

Ms. Draper plays all the characters in Angela’s life with a couple of exceptions, her mother and her ex, who are heard in offstage recordings. During the shorter but succinct second act on opening night, her voice seemed to come around, and she appeared to be on somewhat firmer ground.

One of Angela’s second-act highlights involves a bit of role-playing with two Ken and Barbie dolls, which ends with her whacking Ken with Barbie, sending him flying offstage. Her glee as she does this spreads throughout the entire house. “Think of life as a pleasant meal, and a man as a condiment,” she says, and she sits Barbie down next to a bottle of ketchup. Very, very funny.

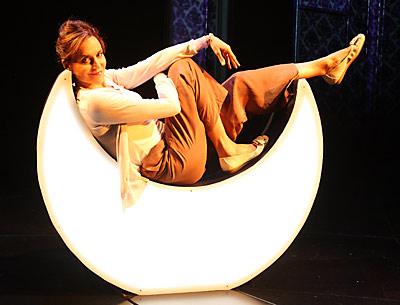

Robin Vest’s set design, using the black-box feel of the space by employing shades of dark brown, gray, and black, is superb, as is the projection design by Aaron Rhyme, the music and sound design by Fitz Patton, and the overall use of the space by the director, Matt McGrath. Mr. McGrath has a strong visual sense, as evidenced by an imaginative use of the revolve, on which he has Ms. Draper slowly step through a dream sequence, to excellent effect.

The costume design by Andrea Lauer made perfect sense, and the lighting design by Mike Billings meshed beautifully with the overall vision of the piece. A couple of light cues were a bit tentative on Saturday, but such is opening night. Tentative.

The occasionally tentative nature of Ms. Draper’s performance may have had its root in her scratchy throat, but two other factors come to mind. The first is a very minor technical point. I was seated near where she makes her entrance, stepping onto the darkened stage from the house. Both times I noted she moved very cautiously as she entered, stepping warily in the dark.

That first moment of a play or an act, when the stage lights burst on or the curtain comes up, is one of the most important of the night. It is the moment that establishes the relationship between the audience and the players. It might be wise to put down a few more strips of glow tape, or perhaps a stagehand with a flashlight, to enable the star to make a smooth transition from off-stage to on.

The second factor is more central to the production.

Driving home from the theater, I wrestled with a memory. Many years ago I saw Joanne Woodward doing a season at Kenyon Festival Theater in Ohio. I consider Ms. Woodward vastly underappreciated as one of the finest postwar American actresses. Ms. Draper, though quite different from Ms. Woodward, shares one thing in common with her: she is very American. She has a down-home American feel to her, an American sensibility and sensitivity. She is an American woman. When she imitates an Englishman, she does so through an American perspective and understanding.

At Kenyon, Ms. Woodward was playing Judith Bliss in “Hay Fever,” Noel Coward’s joyful sendup of English country life. In a setting much like East Hampton, Judith Bliss, a grande dame of the theater, and her eccentric family entertain houseguests for the weekend. I watched Ms. Woodward’s performance several times, and each time there was something missing. As great an actress as she was, this was one part she could not nail.

Her performance was tentative. Why?

Anyone growing up in England has an inborn sense of class difference. Ms. Aron, who was born in Ireland and spent much time in England, clearly has a deep understanding of this thorny subject, an understanding she plays off of throughout the play. Americans, however, have no such divisions. When we speak of class difference, we are actually speaking of money. If you are poor in America, you are lower class; rich, you are upper class. The idea of actually being born into one class or the other is alien to our culture.

“My Brilliant Divorce” is laced with subtle and not-so-subtle references to class differentiation, as is “Hay Fever.” The ability to “get” these differences is essential to play these works as originally written.

This production is attempting, with the playwright on hand and sleeves rolled up, a workaround for that, with the talented Ms. Draper giving her all as an Americanized Angela. Can such a work, idiosyncratic as it is, be Americanized?

I would love to see “My Brilliant Divorce” again, in a week or two, and see how it plays.