Opinion: Chamberlain’s ‘Choices’ at the Guggenheim

There are certain prolific artists whose works always turn up at art fairs or secondary-market galleries. They may be widely popular, but with so much output they risk not always being seen in the best light. Even the best artists have their bad days, or at least their mediocre ones.

John Chamberlain has always struck me as one of those artists. I have walked by his works so often at fairs in Miami or New York City and even in galleries out here, taking them in with a glance of recognition and then quickly moving on to the next thing, barely acknowledging their existence. I have been doing this for so long that I have even stopped noticing whether the example on view is worth a second glance.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s exhibition “John Chamberlain: Choices,” which closes on Sunday, has forced me to reconsider my ambivalence. Just as seeing a great Picasso work at the Museum of Modern Art, such as “Desmoiselles d’Avignon” or one of his analytic or synthetic Cubist paintings, can startle one back into awed reverence, this blockbuster show and its consummate contents are a reminder that Chamberlain was one of the most influential and powerful voices of the 20th century and continues to be in this one.

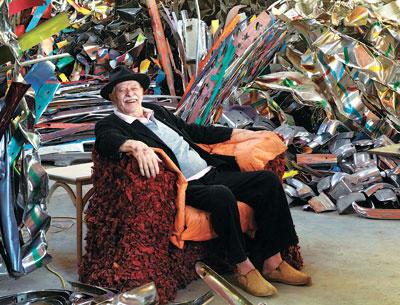

Sadly, it comes at a relevant moment. Chamberlain, a Shelter Island resident who had been ill for some time, died in December at the age of 84. While not planned as a memorial exhibition, the show serves as an apt tribute to the breadth of his achievement as an artist. According to the museum, the title acknowledges the “artist’s process of active selection, or choosing, that is fundamental to his practice.”

His choices were particularly important in his role of bridging the tenets of Abstract Expressionism that he came of age with and the later schools of Neo-Dada, Pop, Assemblage, and even Minimalism into which his work can also be easily absorbed.

It took a while for Chamberlain to find himself as an artist. He was attracted to music first, and then joined the Navy when he was 16, during World War II. After seeing Europe and Asia through his tours of duty, he returned to Chicago and went to beauty school before investigating art classes. Nothing really clicked until he attended the Black Mountain College in North Carolina, an experimental liberal arts college with some of the most distinguished art faculty ever assembled in one place.

Two of Chamberlain’s chief Abstract Expressionist influences, Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning, taught there, but he was also exposed to them through frequenting the Cedar Tavern after he moved to New York in 1956.

Things happened quickly after that. He had a pivotal trip, for him and for local lore, when he traveled to Southampton in 1957. A rusting wreck of a 1929 Ford on Larry Rivers’s property inspired his first sculpture using found car parts. Two fenders, flattened, bent, and then intertwined, became “Shortstop,” one of the earliest works in the show.

While that piece’s sober blackness would fit well with any of Kline’s structural black-and-white paintings, it was Chamberlain’s attraction to de Kooning’s use of color that would dominate his sculpture in the years to come. He was fond of naming the early works after women — “Trixie Dee,” for example, which looks like a big blond Southern belle, or “Miss Lucy Pink,” a voluptuous pink cloud with the sharp-edged menace of one of de Kooning’s “Women.” Even Marilyn Monroe received an homage, buxom and sleek in black and chrome.

He didn’t always work in scrap metal. He might incorporate different materials such as fabric, plastic, portions of a tin ceiling, and staples into a work as if he were composing a collage. It may have seemed as though he was always doing one thing, but there was so much variety in that thing. Then there were also his paintings in high-gloss enamel, filmmaking, foam sculptures, and late photography works. Other materials that got his attention were aluminum foil, paper bags, and Plexiglas.

While each offers a break from the repetition of Chamberlain’s preferred medium, it is almost a relief when he finds his way back to scrap metal, a true love that never really left him. The fact that he continued to find new ways to express himself with it, cutting the metal and lightening up his compositions, demonstrates that he did not tire of it throughout the decades.

In the 1980s his work became more monumental and more expressionistic in its brushwork and forms. Then, more recently, his sculpture changed radically at first, as the Guggenheim describes it, becoming more volumetric and baroque, and then back again to earlier concerns. The last few years of his life brought him back to a supply of 1940s and 1950s automobiles, the metal of which he crushed and stacked vertically and horizontally in large conglomerations, some with the scale and presence of a sculpture such as Auguste Rodin’s “Burghers of Calais.” Working up through his last days, it is tempting to think about the artist grappling with his legacy in those pieces, reaching out once more to the vessel for his grand vision.

The show runs up through the Guggenheim’s spiral, starting early and ending with the latest and last works. At the top of the spiral, as the skylight brings down rays of sun and opens up into the heavens, one can almost sense a risen soul, smiling down on his creation.