Opinion: Emerging? Established?

A relative newcomer to East Hampton, the Halsey Mckay Gallery is committed to advancing the careers of emerging artists — “emerging” might be a stretch, in that Eddie Martinez and Jose Lerma, whose works are currently on view, are precipitously close to becoming established in the contemporary art world.

The gallery strives for interesting pairings. Their shows feature artists who are not an obvious match on the surface, yet may share a particular aesthetic or a perspective that is highlighted and investigated in works that are juxtaposed.

Indeed, though their work is as wildly different as, say, rock opera and a symphony, Mr. Martinez and Mr. Lerma are kindred spirits on many levels. Both reach for abstraction, while holding on to representational forms. In their finished canvases, each artist thinks big — though a series of small-scale studies and drawings upstairs at Halsey Mckay is an interesting key to the artists’ gestational states.

And while both artists keep a toehold in the past, aesthetically and historically, they offer up interpretations that are so fresh and alive that the works feel almost as if they come with their own arch, animated soundtracks. It’s hard to say whether there is a greater advantage in standing back to view their sweep, or to press in close and take in all the surprises of these works piecemeal.

Of these two artists, Mr. Martinez has a more established trajectory. A two-time art school dropout, he apprenticed as a graffiti artist on the railroad tracks outside Boston and San Diego. He was drawn into the studio by a miniature vase, a gift from his mother, into which he put flowers, and started to paint and draw, by all accounts obsessively. His monumental “The Feast for the 2010 Miami Biennale,” an 8-by-28-foot work that begs comparison with “The Last Supper,” put him on an art watchlist — though, as the artist himself points out, the central figure is a clown. Mr. Martinez’s more recent solo exhibitions in Berlin have established that all the excitement was justified.

Interviewers who try to get at his process are met with diffident answers in which art-speak questions end up looking precious and patently ridiculous. He has an almost comical aversion to being aesthetically categorized. He is nonetheless branded, quite logically, as a neo-expressionist. He gives an internal life to his objects that is unlike anything that has come before, in which his graffiti roots and an aesthetic primitivism are clearly visible. His rough, simple objects appear, almost paradoxically, to embody all the noise and movement of contemporary life.

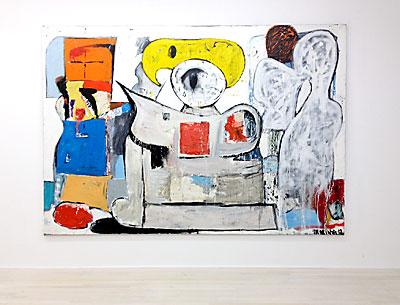

At Halsey Mckay, Mr. Martinez offers up two startling new canvases, “American Native V (Emotional Whiteout), 2012,” and “Untitled (Scullscape) 1, 2012.” These works extend the artist’s preoccupation with studio still life, in which outsized cartoon characters, odd potted plants, and knick-knacks crowd together and demand equal attention from their shared tabletop. In these new works, forms such as a bird’s beak, a wildflower, a pitcher, a ghostly figure, and a cake are faintly recognizable but have taken on more of a splayed, abstracted quality. The artist’s marks are gestural, emotional, and raw. Spray-painted, dripped, and heavily worked passages of bold color are scratched and reapplied. It’s as if Mr. Martinez steeps himself in the discipline of still life — like the heroic painters Matisse and Bonnard — so that he can better hear the call of the wild. The table in earlier works is gone; the artist now seems to live inside his composition.

Both artists cite the naif, cartoon-like quality of Philip Guston and Carroll Dunham as influential to their work. But whereas Mr. Martinez trades in thick paint application and broad strokes, Mr. Lerma combines line and a host of unexpected materials into large-scale portraits that are wry, elegant, and comical, though intentionally not recognizable as the historical subjects on which they are based.

Mr. Lerma was still a law student when, in a visit to the Metropolitan Museum, he was drawn in by the bust of the French banker Samuel Bernard, one of the richest men during the reign of Louis XIV. He shot rolls of film of the bust, which later became a point of departure for a series of paintings. From the beginning, his chief goal was to find ways of collapsing the historical and the personal into a single frame. His subjects rise out of something as simple as a remembered thread of conversation or an event from his youth, and have been translated, notably, into massive, layered “portraits,” constructed from industrial carpet, on which viewers walk.

In four major new works at Halsey Mckay, Mr. Lerma overlays his canvases with swaths of used parachutes in white or pink. Through these veils or scrims, bewigged characters — large, intricate ink doodles, dabbed with tinted spackle — spoof the pompous postures of the grandees and grand dames in the portraiture of centuries ago. More often than not, the subjects have attained lofty goals, only to have fallen into a deep abyss. Mr. Lerma, who was born in Spain, sometimes takes his cue from forgotten figures of his own national history.

The court painter Luis Paret y Alcazar was banished to Puerto Rico by the Spanish King Charles III in 1775 for introducing his younger brother to unsavory women. Paret managed to get himself reinstated by sending Charles a painting of himself deep in the jungle that apparently illustrated his misery. In Mr. Lerma’s interpretive piece, “Luis Paret y Alaczar, 2012,” the artist surrounds Paret’s scantily clad, buffoon-like figure with bananas, palms, and coconuts in a kind of mock sketch for what looks like an official medallion or coin. The circular inscription reads “You get a nerve of Lotta so you can be your friend,” which is a convoluted Web translation into Spanish of, “You got a lotta nerve to say you are my friend” — the opening lyric of the Bob Dylan song “Positively 4th Street.”

In all these large works, the gossamer material of the parachutes the artist uses as overlay creates a tantalizing distance; their seams convert the composition into smaller territories. Are they a metaphor for a fall, the lifeline that failed to open, or the rescue Mr. Lerma offers his subjects by plucking them out of history?

The eponymous actress of “Eleanor Velasco Thornton, 2012” — the mistress of a baron — drowned in the sinking of the S.S. Persia; the diplomat of “Edouard Andre, 2012” contributed to Spain’s loss of Manila in 1898. In “St. Denis, 2012,” the artist collapses the legend of the decapitated martyr St. Denis of 250 B.C. with Dennis Wilson, the “forgotten” member of the Beach Boys band. The 1960s Dennis carries his head between his hands, against the backdrop of a striped T-shirt. Seen through a veil at a telescopic remove, their stories take on ironic and mythical proportions.

The vitality of the pairing of Eddie Martinez and Jose Lerma is marred only by their single collaborative work, “Untitled, 2012,” a small pastel on paper executed the night before their Halsey Mckay opening. The painting looks like two kids duked it out in the sandbox and brute force won. Whether that means Martinez and Lerma, you decide. The exhibit will be on view through Wednesday.