Opinion: Manna at Horowitz

Sightings of literary legends on the East End are almost commonplace, but a look into the heart and mind of Virginia Woolf is a rare opportunity. Through the end of the summer, Glenn Horowitz Bookseller in East Hampton is showcasing an important collection documenting the life and work of the writer and feminist — manna to Woolf enthusiasts.

From the library of William Beekman, the collection is being sold as a unit and, alas, will soon disappear into institutional or private hands. We may never again gain such rich insight into the private Woolf, literary and personal.

While he was still a Harvard undergraduate, Mr. Beekman acquired a first edition of “The Waves,” before the 1972 biography by Woolf’s nephew reignited interest in her life and career. Over 40-odd years, his collection has evolved from first editions of the books to include more personal material documenting her relationship with her husband, Leonard Woolf; her sister, Vanessa Bell; her beloved nephews, Julian and Quentin, and friends and lovers in and outside the legendary intellectual circle known as the Bloomsbury Group.

Here, through Mr. Beekman’s curatorial eye, the Woolf long mythologized as aloof and troubled springs into new life. She is at turns bold and insecure, often funny, loving, insightful, scolding, and even gossipy. “Well, I won’t be indiscreet but between you and me that’s a marriage bound for the rocks,” she wrote about a friend in a letter to Quentin Bell. “Victor would make me shoot him in ten minutes.”

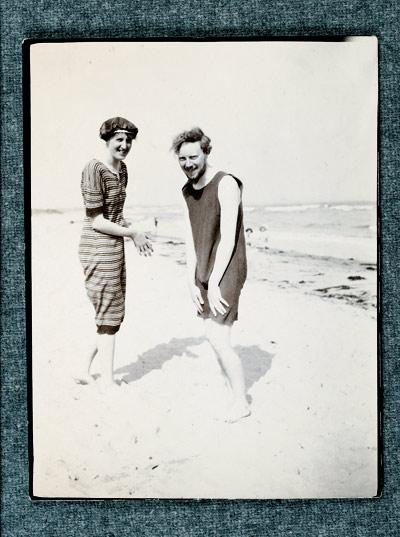

The earliest piece in the collection is a rare and haunting photo, showing “Ginia” Stephen at 13 in mourning for her mother, her dark and melancholy face faintly recognizable from iconic portraits of her later years. Famously, Woolf had her first of several mental breakdowns after her mother died, a loss that was compounded by the death of a half sister and later her father, Leslie Stephen, and brother Thoby. Still another photo shows an unabashedly happy Virginia Stephen at the beach with Clive Bell, just after he married her sister, Vanessa. The exhibition catalog so grippingly describes the context of such photos — a portrait by “devil woman” Gisele Freund infuriated her — you may have to restrain yourself from pulling up a chair and reading it all.

Much has been speculated about Virginia’s relationship with her husband, Leonard, a great deal not flattering to the man himself. This collection focuses on the playful banter of their partnership, in which Leonard was a self-appointed handler. The Woolfs often affectionately referred to each other as “animal avatars” in their personal zoo. In a letter to Vita Sackville-West, Leonard wrote, “I am entrusting a valuable animal out of my menagerie to you for the night. It is not quite sound in the head piece. It should be well fed & put to bed punctually at 11.”

Together, the Woolfs started Hogarth Press, with the purchase of a printing press in 1917. In a letter to their subscribers they explain that they want “to publish at low prices short works of merit, in prose or poetry” that might not be of interest commercially. Their first effort, more of a “hobby of printing,” was “Two Stories,” one by each of the publishers. The print runs of “Three Stories” ended up with three separate covers, bound by Virginia, all of which are on display here.

Hogarth would, of course, become the creative and political forum of the Bloomsbury Group and the fulcrum of Woolf’s writing career. “Yes, I’m the only woman in England free to write what I like,” she reported in her diary in 1925.

What a pleasure it is to see fine first editions with dust jackets of those familiar titles — “Jacob’s Room,” “Mrs. Dalloway,” “To the Lighthouse,” “A Room of One’s Own” — with cover art by Vanessa Bell. The collection includes another important volume, Leonard’s “The Village in the Jungle,” inscribed to Virginia and described as the cornerstone document of their relationship:

I’ve given you all the little, that I’ve to give;

You’ve given me all, that for me is all there is;

So now I just give back what you have given —

If there is anything to give in this.

There were other entanglements. Woolf was more the siren than we might have thought. She turned down a proposal from a married suitor, imploring him in a subsequent letter to abandon hope. But her true love, by her sister’s reckoning, was the writer Vita Sackville-West, whose poetry to Virginia, shown here in two working manuscripts, will sweep you away with its imagery.

Virginia’s homage to Vita was “Orlando,” her mock biography in which the subject inhabits three centuries and two genders. A rare presentation copy of the novel is included here.

From this collection, it is clear that Woolf had abundant love, public recognition, and success that was palpable even to her. Nonetheless, that intolerable “blankness” would again overtake her after her biography of Roger Fry, the artist who had such a profound influence on her lyrical prose. Her finished books always had the effect of abandonment.

A series of eight letters from Vanessa and Leonard to Vita detail Virginia’s disappearance and presumed death. “I think she has drowned herself,” wrote Leonard, “as I found her stick floating in the river. . . .” With stones in her pocket, Woolf had walked into the river Ouse. The collection includes a typescript of Vita’s memorial poem, which concludes, “She has now gone/Into the prouder world of immortality.”

Paula Hayes

Fears about the environment are often expressed in a barrage of punishing facts, but Paula Hayes comes at a solution with a living metaphor. The artist’s miniature landscapes suggest the fragility of our natural world, seducing us into paying attention to what’s going on. Along with her quirky, gorgeous terrariums and botanical sculptures, Ms. Hayes is presenting process drawings of the 1990s at Glenn Horowitz until the end of the month, as well as a driftwood sound piece, a collaboration with her husband, Teo Camporeale.

In pieces such as “Living Time Machine Terrarium TM6,” Ms. Hayes has fashioned lush, tiny landscapes of botanical life in womblike blown-glass enclosures of her own design. The care and feeding of these living works are treated as a formal agreement between artist and collector — a responsibility that becomes a part of the work. Equally beautiful, the Crystal Terrariums are set pieces that incorporate sand, stones, minerals, and crystals, and suggest the complex layers of the earth’s crust. Because of the moon’s profound influence on human habits, their creation is calibrated on lunar cycles. The small botanical sculptures — in malleable, off-kilter containers — have their own demanding personalities. It’s impossible to conceive of them simply as plant life.

“Paula Hayes: Drawings & Objects” is a site-specific exhibition, co-curated by Jeremy Sanders and Stephanie Hodor. The early drawings make this an interesting primer to Ms. Hayes’s work, in which fertility — human, botanical, and artistic — is underscored. Her landscapes and installations have been part of the Museum of Modern Art, the Wexner Center, the Tang Museum, and, more recently, the Lever House. As an accompanying monograph describes, Ms. Hayes catches the zeitgeist of our time, combining art, landscape design, architecture, gardening, and horticulture.