Opinion: Rivers at Stony Brook

One thing I learned about Larry Rivers in speaking to some of the people who knew him best throughout his life a few years ago is that the musician, artist, and bon vivant simply loved people. Be they friends and ever-evolving family, fellow artists, or a parade of girlfriends and wives, he never let a relationship go if he could help it.

For an artist whose life and art merged so seamlessly and who was truly interested in the people around him, it would be unnatural if he had not collaborated with those people. And so he did, and some of the byproducts of that are captured in the current exhibition at the “Staller Center for the Arts” at Stony Brook University called “Larry Rivers: Collaborations and Appropriations,” organized by Helen Harrison.

As summarized in his New York Times obituary: “For a while, he was everywhere. He frequented the Cedar Bar with Willem de Kooning. He designed sets for Frank O’Hara’s ‘Try! Try!’ and for ‘The Slave and the Toilet,’ by Amiri Baraka. His sets and costumes for a New York Philharmonic performance of Stravinsky’s ‘Oedipus Rex,’ conducted by Lukas Foss, outraged music critics.”

“Mr. Rivers appeared with Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg in Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie’s offbeat film ‘Pull My Daisy,’ and played President Lyndon B. Johnson onstage in Kenneth Koch’s ‘Election.’ With Pierre-Dominique Gaisseau, he spent six months making a television travelogue about Africa before being arrested as a suspected mercenary in Lagos, Nigeria, and nearly being executed.”

Ms. Harrison, the longtime executive director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs, has also served as curator at both the Parrish Art Museum and Guild Hall and wrote a 1984 monograph on Rivers. In her essay for the show, she notes the show’s limitations in that it “only hints at the astonishing variety of his artistic achievements.”

Still, there is a lot to take in and the amount of text in these works, his own as well as that of the poets with whom he worked, offers much to chew on visually and aurally, too, if you count the beats of the poems and the musical background in the films.

Although “Stones,” his 1957 to 1959 lithographic series with Frank O’Hara, generates a lot of excitement for its possibilities, it feels ultimately artistically unsatisfying, even when all 12 of the resulting prints are displayed. Perhaps the recent display at the Museum of Modern Art and at Tibor de Nagy Gallery makes it seem a little tired, even if the idea of the collaboration is quite exhilarating. The pictures taken by Hans Namuth of the two of them, lovers at the time, both hands on Conte crayons crouched over the stone, capture the electricity much better than the final product.

O’Hara comes out on top in the effort. His text, such as “. . . it is not the Parthenon/but a Vuillard small/as an Adam’s apple/where pain mounts and falls,” has more staying power than Rivers’s scribbles. It may be, as the artist notes in a quoted passage included on the gallery’s wall, that lithography with its narrow-to-non-existent margin for error is not the natural medium for an artist who called erasure “one of my most important crutches.” His erasure here is just smears while O’Hara’s words are solid and sure, stealing the show.

In other works outside of this medium, and highly personal milieu, Rivers demonstrates his more winning artistic style, real and/or natural, executed in as many mediums at once as he felt like.

His collaborations with Kenneth Koch, another poet, are more engaging. One, titled “Collaboration,” features pencil drawings of artists and writers, sometimes given the suits and numbers of playing cards on scraps of paper applied to one sheet with collaged text by Koch. While the portraits are not exact likenesses, Rivers catches an essence of those he depicts that results in deeper contemplation of their character as it is understood as well as their legacy.

There are a number of other collaborations with Koch on view, including several examples of “Song to the Avant Garde,” a series published in Artforum in collage, pencil, and colored paper. Their “In Bed: Collaboration with Kenneth Koch” has the typical Rivers cheekiness, with the additional twist of a very long Chinese fortune cookie joke. The piece’s cacophony of text, drawing, and appropriated images seems to blare out from afar, but the text is, for the most part, contrastingly rational in its progression and manner. It’s a heady balancing act.

Although the show contains some early works, including a linocut print Rivers made as a cover for Koch’s “A Christmas Play” poem around 1953, most of the works are from the 1980s and 1990s.

Two films by Rudy Burckhardt are shown as part of the exhibition and are must-sees in and of themselves. Both feature Rivers with a cast that, in the case of “A Day in the Life of a Cleaning Woman” from 1953, features Fairfield Porter with his wife, Anne Porter, who is the title character. The film is based on a story by Anne Porter in which a beleaguered housekeeper receives a magic dust brush that makes quick work of the household’s messes. “Mounting Tension” has music from both Thelonius Monk and Duke Ellington and features Jane Freilicher, John Ashberry, and Anne Aikman. There is a great deal of innocent and not so innocent romping in these films that seems ahead of the time, both harkening back to the visual absurdity of silent film comedies and looking forward to the more drug-fueled free-for-all experiments of the 1960s.

The most recent works in the show are a series of appropriations, many of which are based on famous artists and their artwork. They are a virtuosic mix of sculpted foamboard and oil on canvas, almost all from the Larry Rivers Foundation.

Here, in this later work, we see clearly how Rivers, in a vein he chose decades before, helped allow artists to see that they could be both figurative and subversive if they chose to be. As Ms. Harrison noted, the movement that came to be known as Abstract Expressionism adhered to artwork created from interior inspiration, pure of outside influence or taint. Rivers not only wanted to work with others, he wanted to make art about art, too, in a practice that began as early as “Washington Crossing the Delaware” in 1953.

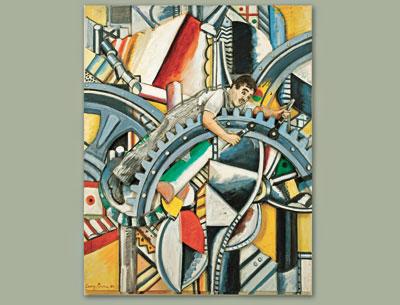

In the 1990s series the art looks amateurish and grand simultaneously and the subject matter often absurd. In “Modernist Times” a Charlie Chaplin tramp-like figure is at work on a giant gear as if he has transported himself into a Fernand Leger painting. The wheels and other compositional elements move in and out of space, varying in depth and projection, providing a rudimentary sense of movement that is fun and kitschy, kind of post-Pop. Other subjects included in the show are Vincent Van Gogh and his iconic chair from the “Bedroom at Arles,” and Matisse’s “La Danse.”

They so well fulfill what the artist’s ultimate goal seemed to be. For all of their art establishment kitschy no-nos, they are irresistible anyway.