Paging Nurse Ratched

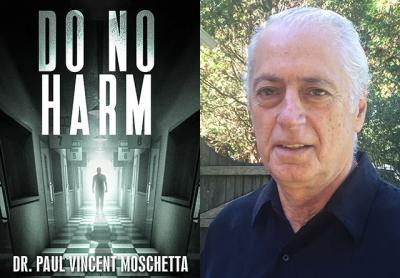

“Do No Harm”

Paul Vincent Moschetta

Post Hill Press, $16

“You are susceptible to very high highs and very low lows,” says the psychiatrist to Andy Koops, the manic-depressive protagonist in “Do No Harm,” a debut novel by Paul Vincent Moschetta, a psychotherapist specializing in marriage therapy with offices in Manhattan and East Hampton. He and his wife, Evelyn Moschetta, have co-authored several books on marriage counseling and were contributing editors to the popular and long-running Ladies Home Journal magazine column “Can This Marriage Be Saved?”

Like Andy Koops, the reader of “Do No Harm” is also likely to experience wild mood swings regarding the merits of this book.

It starts on a high: a near flawless opener that deftly portrays a character who is vulnerable and immediately sympathetic. He is a high school senior in the mid-1960s when his father, suffering from depression, hangs himself one day in the garage of the family’s Oyster Bay home. Andy’s mother is an alcoholic who “sipped vodka in small doses, from 2 p.m. to bedtime, every day,” leaving manic-depressive Andy cutting classes at school and in a perpetual drug haze.

Stoned out of his brains the day his father commits suicide, Andy barely reacts to his father’s death. Fast-forward three years and he’s a junior in college, high on LSD, when suddenly the memory of that day and the pain come rushing back with such “neon intensity” that Andy flies through a psychotic adventure around campus and ends up in the acute services unit at Central State Psychiatric Hospital.

It’s a great preamble for a “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”-type thriller. Unfortunately, the author decides to then take us through a lengthy, and somewhat clichéd, back story of Dr. Enzo Gambelli, who will turn out to be the Nurse Ratched character three years later when Andy, now living in Southampton, ends up back in the psychiatric ward after another psychotic bender has him attempting to steal a plane at Suffolk County Airport because he believes he has an appointment with President Nixon in D.C.

It is only here, some 50 pages into the book, that the real story kicks in. That’s the a lot of throat clearing, and it’s a shame. Dr. Moschetta, who also practiced at two psychiatric hospitals on Long Island, offers what seems to be a keen insider’s knowledge of the abuse that exists in mental institutions and the dehumanizing state of some of this country’s most vulnerable people.

Most people know the axiom taught to medical students, attributed to the ancient Greek Hippocrates but timeless in its quiet sanity: “First, do no harm.” But many doctors do harm, and Dr. Gambelli is one of them. A vividly depicted character, Gambelli is far more evil and twisted than Nurse Ratched, a sadist who runs his ward with an iron fist, keeping patients cowed through abuse and overmedication. He also has a stranglehold on the ward’s charge, a man who basically becomes Gambelli’s bitch by enduring brutal sexual encounters that are not always consensual, told with unflinching detail, and fueled by Gambelli’s inhaling of amyl nitrate poppers, or liquid gold.

Into the story comes Jay Conti, a maverick social worker assigned to Andy’s ward. A contrast to Gambelli’s evil, Jay Conti helps Andy formulate a plan to free himself from the catatonic effects of Thorazine, a mood disorder drug prescribed by Gambelli in extra-large doses because Andy is categorized as “uncooperative.” Jay is there to remind the reader that we go to doctors for help and healing; we don’t expect them to make us worse. But Gambelli’s darkness ensures that the story escalates to remarkably evil heights, all the while punctuated by some blackly comic scenes recounting the absurdities of hospital bureaucracy.

As debut novels go, this is a commendable effort. Although Dr. Moschetta said that he is currently working on adapting the story for the screen, the ending of “Do No Harm” suggests a sequel in the future. Fans of “grip-lit,” as psychological thrillers are sometimes called, will surely be pleased.