At the Parisian Groaning Board

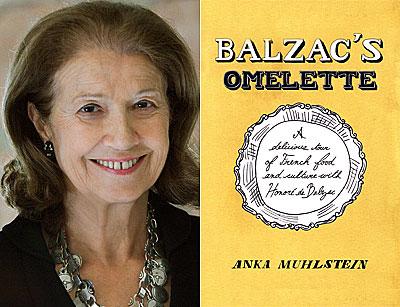

“Balzac’s Omelette”

Anka Muhlstein

Other Press, $19.95

While walking past the New Books table you see a small, square, butter-colored book with an irresistible title — “Balzac’s Omelette.” Don’t tell me you can pass by without picking it up for a look, even if it is just in mute tribute to the correct spelling of omelette.

The subtitle reads, “A Delicious Tour of French Food and Culture With Honoré de Balzac.” You flick through the pages, admiring the charming illustrations. Your eye falls on a few words, telling you that the great writer worked 18-hour days, drinking only water and coffee and eating fruit. Surely not! Balzac was one fat guy!

Then Anka Muhlstein continues, “Once the proofs were passed for press, he sped to a restaurant, downed a hundred oysters for a starter, washing them down with four bottles of white wine, then ordered the rest of the meal: twelve salt meadow lamb cutlets with no sauce, a duckling with turnips, a brace of roast partridges, a Normandy sole. . . . Once sated, he usually sent the bill to his publishers.”

That’s more like it. Balzac was obviously a man to whom food was of paramount importance, to the extent that it is a connecting thread through his novels, revealing his characters’ nature and class through what they eat, when they eat, and where they eat.

“You need only a whiff of the appalling, watery bean soup made by Madame Marneffe’s maid in ‘Cousin Bette’ to gauge how negligent she is in her role as mistress of the house, while the aroma from the hearty limpid stock that Jacquotte serves her master in ‘The Country Doctor’ implies a perfectly run household.”

Considering that Balzac lived in the time of photography, it is strange to learn that when he was born Paris had no restaurants. If you did not eat at home or with friends, you had only the option of dining at an inn or a boarding house, neither of which offered choices or good food. Once the excesses of the Revolution were over, and legal restrictions relaxed, restaurants emerged and at once became an essential of Paris life.

“Balzac takes us all over Paris . . . sending his characters off into the most refined establishments and the most lowly, and through his succession of novels gives us a real social and gastronomic report on the capital. Some forty restaurants are referred to in ‘The Human Comedy,’ because he is not satisfied with mentioning only the biggest names.”

Balzac could certainly put it back with the best — while briefly in jail for the equivalent of draft-dodging, his cell “was piled high, groaning with patés, stuffed poultry, glazed game, baskets of different wines” — but he was a gourmet not a glutton, preferring food of excellent quality, simply prepared with the freshest ingredients. In his books he is as tough on those who eat greedily and indiscriminately as on misers who eat meanly.

Restaurants provide a convenient setting for a novelist to have his characters meet, but it is around the family dining table that they reveal their true natures. Here Balzac reveals his misers — their bread sliced wafer-thin, their meager salads scarcely touched by oil, their tasteless gruels — and the greedy, whose greed he invariably associates with unhappiness in love and life. His most virtuous characters are invariably abstemious. Considering how he liked food himself, it seems a little hard that he doesn’t appear to have portrayed any happy hearty eaters.

“Balzac’s Omelette” is perhaps less of an omelette than a light and charming soufflé. Or perhaps a meze, where you can pick and choose among choice bits of information or anecdote at will. And ultimately it has the effect of awakening your appetite for more than food (which one likes to think is Ms. Muhlstein’s intention), sending you back to the bookshelf to reread Balzac’s novels themselves.

Anka Muhlstein’s books include “Baron James: The Rise of the French Rothschilds” and “La Salle: Explorer of the North American Frontier.” She has a house in Sagaponack.

Sheridan Sansegundo, a former arts editor at The Star, lives in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.