‘The Persistence of Pollock’

Is it possible that someone born a century ago could have upended the conventions of painting so much that his work is just as relevant to today’s artists as it was some 65 years ago when it was first painted?

Few can claim such an impact, but one artist who continues to challenge, confound, and set the benchmark for absolute expressive abstraction well after his death is Springs’s own Jackson Pollock. Whether he is ignored, contemplated, aped, mocked, or appropriated, artists who have followed him have had no choice but to react in some way to his work.

“The Persistence of Pollock,” opening today at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, addresses the ways in which artists of his time and after have reckoned with his legacy.

Bobbi Coller, the chairwoman of the Pollock-Krasner House advisory board, and Helen A. Harrison, the director of the house and study center, served as co-curators of the show. Ms. Coller writes in the catalogue essay that “when Pollock first started to exhibit his singular and revolutionary poured paintings, he caused an earthquake that shattered the syntax of visual language, destabilized fundamental expectations of how a painting should be made, and liberated future generations of artists.”

It wasn’t just the work that made him an intractable part of the American artistic imagination, but his persona as well. The swashbuckling, womanizing, fireplace-pissing, cantankerous drunkard, who was tamed for a time by his wife, Lee Krasner — who brought him the sobriety and space to have the breakthroughs we so celebrate — is still the Pollock legend most prevalent in people’s memories. While Krasner tried to quell the myths in the legend, they were in the end too powerfully irresistible to anyone who wanted to believe the tortured-artist stereotype was true.

As the curators point out, both art and persona combined to inspire “numerous creative responses in many forms: musical compositions, poems, novels, choreography, performance art, a superb film with Ed Harris, and a one-act play by his friend B.H. Friedman.”

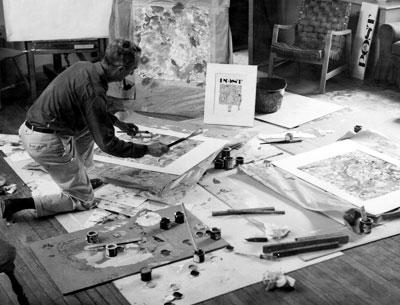

For the purposes of this show, it is the visual artists of this and the prior century who will be presented. Expected names like Pollock’s friend Alfonso Ossorio and artists known for appropriation or transgression such as Mike Bidlo and Vic Muniz join the unexpected. Some of the more surprising artists include Janine Antoni, whose work typically involves elements of performance that can, in this instance, be likened to action painting, and Norman Rockwell, surely one of the most conservative artists of his day. In 1962, Rockwell transformed his studio into a space where he too could crouch over a canvas and splatter his paint for a Saturday Evening Post cover called “The Connoisseur.”

The inclusion of Lee Ufan, a Korean who moved to Japan in 1956, is indicative of how Pollock’s work infiltrated even Eastern cultures, influencing both the Japanese Gutai Art Association and Mr. Lee’s Mono-ha movement. Ms. Coller noted in the essay that Mr. Lee’s piece in the show “Pushed-Up Ink” is the result of pressing an ink-filled brush against paper in a way that “creates a rhythm that is both intoxicating and expansive.”

Others who join in the homages and challenges to the Oedipal father figure include Robert Arneson, Lynda Benglis, Arnold Chang, Francois Fiedler, Joe Fig, Red Grooms, and Ray Johnson.

The exhibition will be on view through July 28.