Peter Lipman-Wulf in Color

Paintings by Peter Lipman-Wulf, currently on view at the Romany Kramoris Gallery in Sag Harbor, beckon from the sidewalk in a pleasant way. Two of his watercolors on paper, casually tacked on boards, have been placed on easels in the storefront windows. The presentation is charmingly reminiscent of street art vendors in Paris along the Seine.

On a gray day with rain threatening, their colorful palette and provincial European scenes offered a hint as to what is inside. The paintings, primarily of Switzerland and France, capture a world untroubled, at first glance, by the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany and the artist’s self-imposed exile.

Fired from his post at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin in 1933, Mr. Lipman-Wulf, a Jew, left the city of his birth and went to France, where he was interned in a camp in Provence from 1939 to 1940. He escaped to Switzerland in 1942 and immigrated to the United States in 1947. He lived in New York City and eventually came to Sag Harbor. He died in 1993 at the age of 88.

His preferred medium was sculpture, but during the ’30s and ’40s he was limited by his circumstances in finding materials. Instead, he took a simpler route, mostly doing drawings and watercolors.

The works at Kramoris are a mélange of Fauvist inclinations and German Expressionism, sometimes recalling Van Gogh and Cezanne and other times Kandinsky. Many scenes look very familiar as Cote d’Azur subjects, but it is sobering to realize that this beautiful place was also the site of his imprisonment.

The Swiss paintings are more muted, no doubt reflecting a change of climate and light, but also a change of mood. As a refugee, Lipman-Wulf was not allowed to practice his métier in sculpture, and he continued to draw and paint on paper. The use of black in his compositions seems to become more prevalent. A painting of the Rhone Valley features a brown landscape with stone buildings that look not unlike tombs and grave markers.

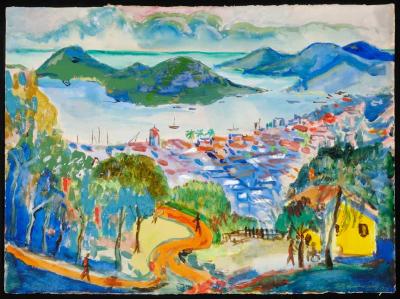

There is one watercolor from 1950 from the Cote d’Azur which, if the date is correct, shows a tremendous capacity for forgiveness. The landscape, viewed from on high, reflects the way the Mediterranean coastline moves quickly from sea level to hilltop. It shows a town tbat descends to meet the water.

For those used to Lipman-Wulf’s career-defining abstract sculptures and portrait busts, some of which were commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera, these works may seem a minor diversion. Yet they show an artist using the materials at hand to continue to interpret the world around him at a time when it would have been easy to throw up his hands and not go on.

The show will remain on view through Nov. 21.