A Picture Is Worth 25 Lives

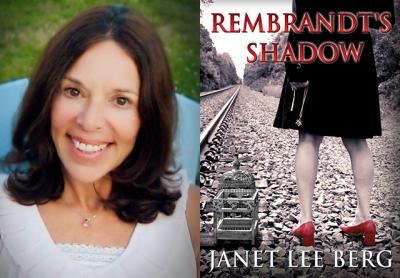

“Rembrandt’s Shadow”

Janet Lee Berg

Post Hill Press, $15

In the 72 years since it ended, World War II has provided us with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of stories, a global event that has kept on giving. Just when one thinks the stories have all been told, the emotions have all been felt, the survivors almost all now gone and buried, we are presented with another novel or movie or memoir. Perhaps the injunction to “never forget” has become unnecessary with new stories forever emerging to remind us.

Janet Lee Berg’s novel “Rembrandt’s Shadow” tells a story she describes as “loosely based” on wartime experiences of the wealthy bourgeois Katz family: Benjamin Katz was the grandfather of her husband, Bruce Berg. In many ways this is an all too familiar World War II story, containing as it does the iconic elements of loss, degradation, dislocation, resilience, but also, here, of suicide, the ultimate human failure of resilience.

Because we have seen these elements in numerous movies and television productions, in photos, books, and museums, Ms. Berg’s words easily evoke the corresponding images from 1940s Europe, a period and a reality that she presumably knows only indirectly. In contrast, from her references to Long Island’s cultural life in the 1970s, one may presume from its lively details that she was a participant in that culture.

“Rembrandt’s Shadow” also transcends the familiar: Ms. Berg borrows from lesser-known, actual events that involved her husband’s family during the war, when the brothers Katz, art dealers renowned well beyond their hometown of Dieren in Holland for their expertise in the Dutch masters, negotiated with agents of the Nazi leadership to exchange these paintings for Jewish lives, a bargain with the Devil if ever there was one.

Hermann Goring, Hitler’s art expert, actually visited the family’s home in 1940, standing in their living room as one such negotiation took place. The imagination leaps to a scene where one such masterpiece is transferred from reluctant Jewish to grasping Nazi hands, as the silent family looks on. The most significant of these trades was the exchange of Rembrandt’s “Portrait of a Man” for visas that permitted safe passage for 25 members of the Katz family, including the mother of Bruce Berg and his sister.

In 2007, Katz heirs on Long Island filed a claim with the Dutch government for the return of more than 200 works of art now held in Dutch museums. The claim is under dispute until it is determined whether any or all of these works were sold forcibly or voluntarily, depending in part whether they were sold before, during, or after the war. The most recent available information about the disposition of the art comes from newspaper reports published in September 2007.

In Ms. Berg’s fictionalization, the Katz family becomes the Rosenbergs, with Sylvie, the second of four children, at the story’s heart. As in the real-life story, the family lives in Dieren, in a milieu of affluence and privilege that captures Jewish life in Holland from the 1930s to 1941, before and during the Nazi occupation. Sylvie’s father, whom she adores and who treats her as his favorite, is often absent, traveling to promote his art business as he generates the wealth that permits her mother to be a socialite, indulging herself in fashion and luxury while neglecting her children and relegating their care to the “waitstaff.”

Although the framework of art exchanged for Jewish lives provides “Rembrandt’s Shadow” with a dimension not found in other World War II memories, Ms. Berg also invokes what have become the familiar early signs of encroaching Nazism: playground bullying and ostracizing by German children of their Jewish classmates; the gradual dawning realization that neighboring families have disappeared; sights and sounds of uniforms and boots on quiet, cobbled streets; sudden airplanes in the quiet skies; buckling affluence and the decline of lavish parties, expensive clothes, cigars, and champagne; the leg of lamb replaced by spaetzle; the maid leaving because Germans are forbidden to work in Jewish households; closed doors behind which anxious adults whisper and confused children eavesdrop; yellow Jewish six-pointed stars sewn onto coat sleeves. And that final, dreadful day when the family closes the front door of their beautiful home behind them for the last time, standing silently with other Jewish men, women, and children on railway platforms as they leave the known and the precious behind for what turns out to be forever.

It is an old, familiar story of loss — of life, identity, and the predictable. However, with safe passage assured by the Rembrandt painting, the Rosenberg family is taken to Spain and then to an internment camp in the West Indian island of Jamaica, where they spend the war years. (Despite my own internment and refugee background, it was a surprise to learn that Jews were interned in the Caribbean.)

“Rembrandt’s Shadow” unfolds in chapters headed by time and place, from the 1940s to 1969 to 1972 and from Holland to Long Island — Massapequa and Queens — Las Vegas, Tennessee, North Carolina, Thailand, and (a tourist visit) Dachau. A note to the author: This back and forth is somewhat of a distraction that for this reader disrupted the story’s flow. Designating the chapters as, for example, Sylvie’s story or Helene’s (her mother), Michael’s (her son), and Angela’s (her son’s girlfriend) might anchor the story in human rather than geographical or temporal terms.

After the war, the family is dispersed — Sylvie and her mother to New York, the siblings to England. Sylvie’s story recedes from its central place, displaced by the next generation’s love story set against the Vietnam War, yet retaining the themes of separation and loss redolent of the years in Europe.

Much of the book’s texture emerges from four of its themes: mothers, interfaith tension, the written word, and secrets. Since Sylvie is 16 when the Rosenberg family is forced to flee Holland, she will have struggled with her distant, distracted mother into her teenage years. When she herself becomes a mother, her son, Michael, leaves home, taking to the open road in his struggle to escape from his overly protective, demanding mother.

Sylvie is unable to accept Angela, Michael’s Catholic girlfriend, who escapes her loving but suffocating Italian mother. (Ironically, Ms. Berg has dedicated the book to “Mother.”)

Although the Rosenberg family is secular, Sylvie’s is hostile to Angela because she is not Jewish. While less hostile, Angela’s mother expresses her displeasure at her daughter’s love for a Jewish man. These interfaith tensions are enlivened by the travels of a golden Star of David necklace through the lives and generations of both families.

Secrets weave in and out of “Rembrandt’s Shadow”: an unknown, now dead sister, a rape leading to an abandoned brother, jewelry hidden from a mother, love letters never sent and then stolen.

Finally, the novel’s fourth and epistolary theme is manifest in love letters, family correspondence, and a diary, as well as in conversations with a cat. Although Michael is a writer, we don’t see his work, but we do know some of his thoughts. (Interrupting a story with an epistolary or journal entry break is a tried-and-true writer’s device, but another note to the author: Not all of the journal’s entries in this book appear to have been written by the same person.)

As this reading of “Rembrandt’s Shadow” by Janet Lee Berg demonstrates, there is always room in the Western literary tradition for one more story from World War II.

Hazel Kahan is a writer and programmer at WPKN radio. She lives in Mattituck.

Janet Lee Berg, a Star contributor for many years, will read from “Rembrandt’s Shadow” at BookHampton in East Hampton on Friday, May 12, at 5 p.m.