Poems for Fractious Times

“Pushcart Prize XLI”

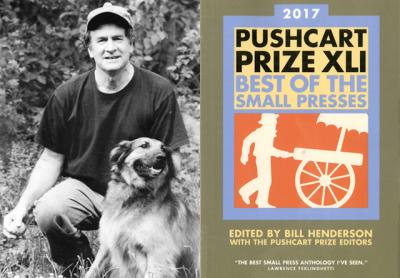

Edited by Bill Henderson

Pushcart Press, $19.95

The poems in “Pushcart Prize XLI,” which anthologizes the year’s best fiction and essays, edited by Bill Henderson with the Pushcart Prize editors, reflect a wide range of voices in contemporary American poetry. The narrative mode dominates as each poet tells his or her tale. But it is a fragmented and interrupted narrative that reflects the disjuncture of American life.

Suffering, for example, is shown through the surreal, as in Mathias Svalina’s “From Thank You Terror,” which describes being beyond death. The poem begins “I was dead / but they kept killing me / by the seaside” and is soon followed by questions: “But where is the sonnet of power? / Where is the sonnet of suffering?” Mr. Svalina’s almost-answer is “when the skin comes off / it comes off like a shower curtain.” Hardly sonnet-like, but the image packs power.

In “I Dream of Horses Eating Cops,” Joshua Jennifer Espinoza uses the sardonic metaphor of a rebellious carnivorous horse as escape from things as they are: “My dad was a demon but so was the white man in uniform / who harassed him for the crime of being brown.”

Animals suffer, too. Robert Wrigley in “Elk” describes an elk falling through the ice, freezing to death, and being eaten by coyotes. The coyotes in Jane Springer’s “Walk” did not want the meat of an accidental kill that she encounters on a walk “in these woods.”

Themes of alienation and prejudice dominate the collection. For example, Sally Wen Mao in “Anna May Wong Blows Out Sixteen Candles” shows us how Asians were cast as stereotypes in movies through the voice of Wong, who was cast as a woman who pours someone’s tea and was held “at knifepoint, my neck in a chokehold.” Her role: “If they didn’t murder me, I died of an opium overdose.” The central image is of a boy in school who stuck needles in the speaker’s neck, asking, “Do Asians feel pain the way we do?”

Adrian Matejka addresses the issue of color in “The Antique Blacks.” His poem interrupts narrative, leaping from “In Richard Pryor’s origin myth of black / size, the two most magnanimous black men / in the world are peeing off the 30th Street Bridge” to the speaker’s personal experience: “It’s like back in Indiana, where my white / mother said, You are black because my black / father’s jurisdiction includes the skin heliotrope / I’m in.” Images of blackness like the first black man in outer space are juxtaposed against whiteness: “Him & his pack of white / friends — a flotilla.” The poem, long, dense, and angry, must be reread for full comprehension of the nuances of color.

Another poem that departs from conventional narrative using paragraphs and indented lines to show prejudice is James Kimbrell’s “Pluto’s Gate: Mississippi.” It is spoken in a colloquial voice and deploys unusual and strong similes; “my face stinging like a voodoo doll,” and “white as God’s white-ass golf balls.” He shows time and place — Starbucks, a Plymouth push-button Belvedere, a pool hall — to dramatize class and racial differences between blacks and whites in Oxford, Miss.

Poems of a son’s relationship to a father include Martin Espada’s “The Beating Heart of the Wristwatch,” with its pessimistic ending, “We try to resurrect the father. / We listen to the heartbeat and hear the howling.”

David Tomas Martinez uses the mythic father as king with absolute power to show the everyday experience of male power through the figure of Oedipus. The poem, “Consider Oedipus’ Father,” begins, “It could have been a car door / leaving that bruise, / as any mom knows, / almost anything could take an eye out.” It should also be noted that Mr. Martinez pays tribute in this poem to William Carlos Williams’s red wheelbarrow.

There are other family poems, like Kate Levin’s “Resting Place,” which merges the theme of the death of a bird with her fear for her son’s safety. Death is paramount in these poems, as in Jean Valentine’s “Hospice,” which begins with the poignant “I wore his hat / as if it was the rumpled coat / of his body, / like I could put it on.”

Tatiana Forero Puerta’s “Cleaning the Ghost Room” confronts the issue of how we face the dead through the trope of mother and daughter. The speaker’s mother makes her clean and dust “the ghost room” where Mr. Traynor died. When she objects, her mother tells her, “You want the dead on your side.” She recalls her fear and dislike of her mother: “I held the / can of Pledge, an old sock rag, and / antagonism for my mother.” The poem suggests the complex feelings she has for her mother and how to confront death. If as a girl she hadn’t dusted “the accruements / of the departed,” she might not be able to “polish the rust / off the roses — embossed in the bronze of Mami’s urn.”

The poems selected for “Pushcart Prize XLI” speak in bold and varied voices using imagery that ranges from movies to myth to capture life and death in contemporary America. They are a pleasure and an education to read.

Carole Stone, professor emerita of English at Montclair State University, is the author of poetry collections including “American Rhapsody” and “Hurt, the Shadow: The Josephine Hopper Poems.” She lives part time in Springs.

Bill Henderson lives in Springs.