Pollock: Family and Friends

There have been several exhibitions and related events surrounding the 100th anniversary of Jackson Pollock’s birth in January. While not a cause for celebration, the anniversary of his storied death just passed on Saturday.

Although not specifically tied to these events, a few recent books have also addressed aspects of Pollock’s life and his influences. Last summer saw the publication of Gail Levin’s definitive biography of his wife, Lee Krasner. A book on Thomas Hart Benton by Justin Wolff (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, $40) covers the life of another caretaker of Pollock as well as a formative influence on the young artist.

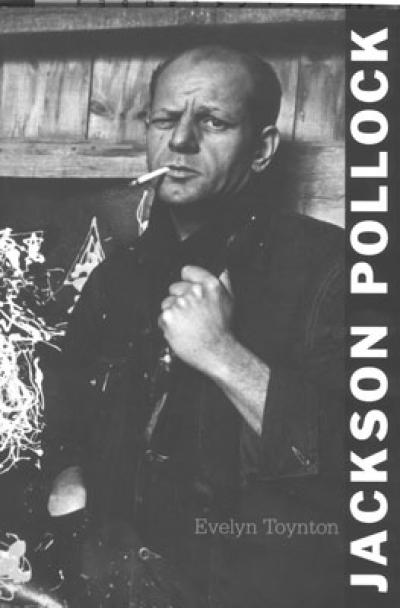

Two other recent books, Evelyn Toynton’s “Jackson Pollock,” part of the Yale University Press’s Icons of America series ($26), and “American Letters 1927-1947: Jackson Pollock and Family” (Polity, $25), contribute to the rather large existing canon of publications devoted to the artist.

Ms. Levin’s book, reviewed in The Star last summer, is the best in this class in terms of insight and historical fact. The book about Benton is also a thorough treatment of Pollock and an analysis of why his art did and then did not matter to 20th-century viewers and beyond.

The two books exclusively about Pollock are not definitive, but both serve their individual purposes well. Ms. Toynton’s is a slim monograph that sets the artist in the broader context of his times. The basics familiar to anyone with working knowledge of Pollock’s life, e.g., his relationships with his brothers and mother, his relationship with Benton, his meeting Krasner, the mural for Peggy Guggenheim, and so on, are all there — as are reminders of what the art world and greater world around them were experiencing in the years of the Depression, World War II, and after, that made his contributions to those worlds at those times so meaningful.

It is a good book to sit down with for an evening and walk away with a decent understanding of who the artist was and what he was trying to accomplish. It also looks at Pollock’s mysticism, his Jungian analysis, his alcoholism, and the influence of the Surrealists on his work. It’s not a biography so much as a portrait of an artist during the prime years of his life and the external forces that shaped him.

As such, it still has its ambitions. Ms. Toynton sets out to debunk the myth of the “Cody, Wyoming Cowboy” that always serves as a facile way of summing up his outsider and outlaw persona. She points out that Pollock may have been born there, but with two vagabond parents was gone by the age of 10 months. He did live in the American West at various times in his youth, but spent just as much time in California. Still, the openness of that terrain and the sand paintings made by Navaho tribal members would have a great influence on his mature work in the way he laid out the large canvases on the floor and would paint with twigs and other unconventional tools. It was a myth that he seemed to play up in New York as well.

A show on view through October at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs looks at the influence of Jose Clemente Orozco, a painter Pollock and his brothers became familiar with in their travels and at home, but Ms. Toynton states that Pollock’s use of common house paints and auto enamels was actually something he learned from another Mexican muralist, David Siqueiros.

In an interesting contrast between books, Ms. Toynton sees the Pollock-Benton bond as a kindly, nurturing one, describing Pollock as being quite attached to Benton’s family and spending summers at their house on Martha’s Vineyard. In Mr. Wolff’s book, it sounds more tempestuous and Oedipal in some ways: Pollock’s rejection of Benton’s art and his sexually charged relationship with Benton’s wife even as he was baby-sitting and doing errands for them in exchange for their support.

Both men apparently were hard drinkers and surly in their interactions. Before Pollock moved into a fuller abstract mode, he seems to have had nothing but respect for Benton. He later disavowed his mentor’s influence in his work.

In the book of Pollock family letters, edited by Sylvia Winter Pollock with an introduction by Michael Leja, a more personal and firsthand account emerges. Mr. Leja contributes a well-ended summing up of the family’s background and the forces shaping their choices of profession, politics, and places of residence throughout their lives.

He notes, as is also evident, that much of the mythology surrounding Pollock melts away in these personal messages to the people who knew him best. There are letters between the parents, LeRoy and Stella Pollock, the five Pollock brothers — Charles, Marvin (known as Mart), Frank, Sanford (known as Sande), and Paul Jackson (known as Jack and later Jackson) — their wives, and associates. Pollock’s family background was complex and unconventional. His father, who was born LeRoy McCoy, was left to work with a farm family whose last name was Pollock when his parents found themselves too poor to raise him.

LeRoy left a similar legacy to his children. After a series of economic failures, he left his family in California to find his fortune. Although he continued to support them as much as he could financially and saw his sons on extended visits, he was never really part of the family household after a time and chose not to live with their mother even when he had another chance to try.

One of the earliest letters is a warm discussion between LeRoy and a 16-year-old Jackson of a previous letter about religion. It is a simple but emotionally full note that makes their arrangement seem not so terrible after all. Through the 1930s there are letters with news of marriages and union and political activity. The 1940s chart the course of Pollock’s increasing success and notoriety and his evident pride in it.

The book is likely to appeal primarily to Pollock enthusiasts who have exhausted other biographical sources, but it is also a fascinating firsthand portrait of an American family struggling through challenging times.