Portrait in Bravery

Rebecca Alexander is a force to be reckoned with. At the writing of this memoir, she is in her early 20s. She is accomplished, vivacious, active, energetic, and derives a great deal of satisfaction from helping others. She has taught in a prison; she has volunteered for Project Open Hand, a nonprofit organization that delivers meals to people living with H.I.V./AIDS.

Ms. Alexander earned a master’s degree in public health and a second master’s in social work, both from Columbia University. In addition, she has trained at a psychoanalytic institute, received a certification in psychodynamic psychotherapy, and works full time as a psychotherapist. She also works as a spin instructor.

She is an extreme athlete who has run with the Olympic torch as a Community Hero and successfully completed a five-mile lake swim and a 600-mile AIDS/LifeCycle bike ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

As if all of this were not enough (and there is more, much more, far too much to mention in a book review limited to a mere 1,200 words), she has accomplished all of this while becoming steadily deaf and blind. Because of a rare genetic disorder called Usher syndrome, Ms. Alexander is eventually heading toward a condition called deafblindness. Yeah, that’s what Helen Keller had.

At the moment, Usher syndrome is irreversible, untreatable, and there is little, medically, to be done about it, other than await the inevitable decline. This, however, does not stop Rebecca for one instant. She is doing anything but going gentle into that good night.

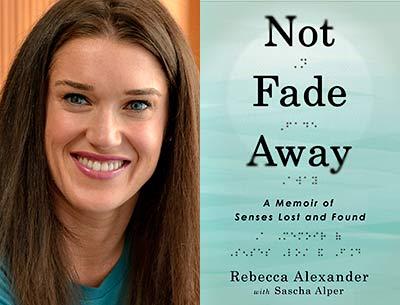

Her book, “Not Fade Away: A Memoir of Senses Lost and Found,” is nicely and movingly written (co-written with Sascha Alper) and, surprisingly, possesses tremendous cheerful humor. Despite her downward spiral of lost senses, the memoir contains not a shred of self-pity. Not an iota. None. Really.

Rebecca keeps a positive attitude without sounding in the slightest Pollyanna, saccharine, or unrealistic about what she is experiencing. She allows herself deep sadness at her losses — and at her impending even greater and more final losses — but throughout this impressive memoir she manages to maintain a tone that demonstrates her bravery, defiance, determination, and, yes, even humor.

Ms. Alexander had a pretty normal childhood, though she admits to being unusually klutzy, which may have been an early herald of her syndrome, as her hearing may have already been slightly compromised, and one of the hallmarks of Usher syndrome is vestibular dysfunction, which may cause imbalance and spatial disorientation.

Then, at 18, already feeling the beginnings of the decline of her senses, she comes home drunk one night and on her way to the bathroom accidentally tumbles out the window of her second-floor bedroom. She falls “backward more than twenty-seven feet onto the flagstone patio behind our house, landing, miraculously, on my left side, breaking almost everything but my head and neck.”

The fall leaves her needing several surgeries. “Ultimately, the only thing left without a cast would be my right leg and foot.” There follows a two-page description of the difficulties involved in being able to pick up a pen with her foot. Already going blind and deaf, and now this. Can we say “the trials of Job”?

Ms. Alexander describes where she acquired her positive attitude. “When we spend time together now, both with our hearing aids, me with my cane and her with her walking stick, Grandma Faye is a living example of what she taught me then. Nobody wants to hear you complain, so keep the bitching and moaning to yourself. Embrace the world with a positive outlook, and you will get so much more out of life.”

She writes:

. . . I wouldn’t wish what I have on anyone, and would never have chosen it, but it has given me an extraordinary ability to understand profoundly what living in the moment really means and to always try my best to do just that.

I don’t mean living each day as if it were my last. I have been there, done that. I’ve gone bungee jumping and skydiving. There have been times when there were too many guys, too much drinking, a never-ending whirlwind of “let’s grab life by the balls” . . . but never pausing to catch my breath is not the way to appreciate a world that is slowly — and sometimes not so slowly — going silent and dark for me. And while mine is an accelerated decline, one that will leave me with decades of blindness and deafness — many more than I’ll spend with hearing and vision, if I live a long and healthy life — the end is inevitable for all of us. In some ways, I feel lucky to never be able to forget that.

I found myself quite moved when she writes, “Sometimes I can’t help but wonder how it will be at the very end, though I try not to. Will I have a last clear image that I see, before my pinprick of a hole [her vision is blackening inward, contracting toward the center, which is still mostly clear] finally closes up forever? Or will things just blur more and more, an impressionist painting that gets increasingly less recognizable until finally it’s just a swirl of fading color, and then nothing? Will the last authentic sound I hear be a laugh, a cry, a subway rumbling into the station?”

In order to maintain a semblance of normal life, Ms. Alexander has had to learn sign language and Braille. She must use a cane and has three different hearing aids for different environments and a cochlear implant in one ear. Mind you, this does not stop her from being quite active in the New York City dating and singles scene. Talk about valor! Dating is tough enough when you can see and hear most of what is going on.

But as her vision and hearing continue to fade away, she will be unable to see others sign and will at some point be reduced to tactile signing, “the language used by people who are both deaf and blind.” Her description of learning this, and doing it with her best friend, Caroline Kaczor, a 2006 graduate of East Hampton High School, is at once lovely, poignant, intimate, and deeply frightening to me, who is merely facing the normal declines of age.

We’ll lie facing one another, and she’ll take both of my hands and place hers inside them. As her hand begins to take form, I’ll start to sound out the word she is spelling in my hand, listening intently with my palm and fingers, closing my eyes to help me focus. While I hold and follow the movement of her hands, Caroline will bring her pointer finger to her chest, and I’ll speak aloud what she is signing. . . .

At first we were terrible at it, and I would start to giggle at every mistake . . . and though I couldn’t hear Caroline, I knew she was giggling, too, because I could feel the quick little bounces her upper body would make against the bed. . . . Caroline could hear the sound of my laughter loud and clear, but she knew that I couldn’t hear hers, so she would take my hand and place it against her neck right at her vocal cords, so that I could feel her laughing, which made me laugh even harder.

. . . Watching people tactile-sign is like watching two people embrace, an elaborate dance of hands and fingers.

This book, a brave and affecting and funny account of a horrible and frightening illness, made me laugh and cry and feel truly and deeply moved. It does not seem like the kind of book one would enjoy, but I did enjoy it. I also think that I am going to buy several copies and give them to people I know who are facing some tough illness or period in their lives. “Not Fade Away” is a blueprint for handling the ugliest kind of shit life can throw at you, with grace and guts and courage. Bravo, Ms. Alexander!

Michael Z. Jody is a psychoanalyst and couples counselor with a practice in New York City and Amagansett.