The Power of Games

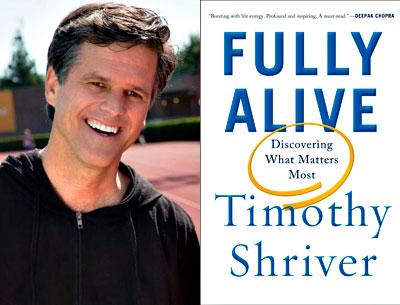

“Fully Alive”

Timothy Shriver

Sarah Crichton Books, $27

Books are a central part of my holiday ritual — perusing the year-end “best of” lists, choosing just the right volume to give to each special person in my life, and then curling up on the sofa with those I’ve picked for me.

This season my heart was moved by “Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most” by Timothy Shriver. In the interest of full disclosure, I know Mr. Shriver, but through his new book I feel I’ve come to know him on a deeper level . . . and my admiration for him has only grown as a result.

“Fully Alive” is hard to categorize. It’s an engrossing history of the disability rights movement and the creation of the Special Olympics. It’s a love story. It’s a profound meditation on meaning. It’s a memoir. But what ties all these disparate threads together is Mr. Shriver’s rare ability to talk about love, belief, and destiny without being trite or preachy.

The book opens as Mr. Shriver remembers holding “boat races” with his mother, Eunice, in the stream behind their home when he was just 5 years old. Their boats were made of small sticks, and the twiggy craft that could navigate the current and float downstream first won. “In those days of boat races, I believed. I believed in things I couldn’t see and in the secret power I had to change the world into a place of love and mystery and eternity,” Mr. Shriver writes.

The simple, intimate scene foreshadows themes of his life: the importance of imagination, the power of games, and the primacy of family.

Indeed, family sets the stage in “Fully Alive” but not in the usual way — and certainly not with the clichéd stereotypes of glamour and prestige to which so many books about the Kennedys cling. Mr. Shriver recalls, for example, how his grandmother Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy used to paraphrase Luke 12:48 — “Of those to whom much is given, much is expected.”

As a political enthusiast with no strong religious affiliation, I never recognized that famous phrase as a biblical reference. Wrongly, I always credited the line to one of President Kennedy’s speechwriters. Knowing that this bold pronouncement about what the privileged owe society was a message born in faith and ingrained in secular family values is to understand a great deal more not only about the 35th president, but also about Tim and Eunice Shriver.

The story at the heart of the book is that of Rosemary Kennedy, daughter of Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy and sister to President Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Eunice Shriver. The book puts a spotlight on Rosemary’s intellectual disability and its “heartbreaking” impact on the family. Despite Rosemary’s condition, which culminated in a lobotomy that left her permanently debilitated at the age of 23 — or maybe because of it — the family grew stronger, closer, and more committed to working for the truly vulnerable members of society.

The book also reveals how Eunice Shriver coped with the devastation of having one renowned doctor after another tell the family there was “nothing that can be done” for Rosemary. Rather than curse the darkness, Mrs. Shriver lit a candle and started Camp Shriver. In the very same backyard where she and Tim had raced their boats made of sticks, she created a retreat for disabled children. She used her family’s power, including that of the president, to advance the needs of people with disabilities — people like Rosemary.

In 1961 President Kennedy announced the establishment of the historic President’s Panel on Mental Retardation. He’s quoted in the book as saying, “This is a matter which I think should be brought out into the sunlight. . . . It is high time that the country give its time and attention to this.” The report stands today as a landmark in public policy in providing recommendations, treatments, social services, and much more for millions of families with a member with intellectual disabilities.

Ultimately, Mrs. Shriver started the Special Olympics — the very organization Mr. Shriver chairs today. As the reader learns about the beginning and then expansion of the games, it is the athletes who are the stars. We meet several, including Marty Sheets, a young man who in the first Special Olympics won a gold medal for bravery, and Loretta Claiborne, a runner turned global spokeswoman for the cause. Today, the Special Olympics provides training and competitions to more than 4 million people annually in over 170 countries.

Mr. Shriver chronicles his personal quest to make his mark. It’s not an easy road. He teaches high-risk, underprivileged children but fails to connect. He seeks meaning through religion but finds something less than total satisfaction. Along the way, he questions everything and everyone — including the pope and Nelson Mandela. His self-described quest to “be Tim” could have easily fallen into self-serving, navel-gazing psychobabble, but his well-told stories, clear-eyed self-deprecation, and excellent writing make the story an endearing one.

He is lucky to have traveled in the slipstream of history. Like African-Americans during the civil rights movement, women who instigated and continue to propel the modern feminist movement, or gays who’ve made remarkable progress toward equality, Mr. Shriver and the athletes are swept up in a larger unfolding drama. In their case it was the movement to receive intellectually disadvantaged people as complete, valuable members of society, instead of marginalizing them.

“Light is always breaking through from within us and all around us. Once in a while, we have the mind and heart to welcome it. And sometimes, more rarely, we experience the joy of welcoming it together with others. That is what happened the morning of July 20, 1968,” Mr. Shriver writes. That summer morning the first-ever sports event called the Special Olympics took place on Chicago’s Soldier Field.

In “Fully Alive,” Mr. Shriver discovers a lifetime of mornings like that day in 1968, becomes a crucial player in the disability rights cause, and answers in his own terms what it means when “much is expected.”

At this time of year, in addition to trying to make a dent in the pile of books on my nightstand, I also make resolutions — ones that usually fade by February. “Fully Alive” may encourage readers — as it has inspired me — to make real and lasting commitments to discovering and acting upon that which matters most.

In fact, in the final paragraphs, Mr. Shriver encourages his children with a phrase from Ms. Claiborne, the Special Olympian turned spokeswoman, to “Storm the castle.” Mr. Shriver explains, “If you are who you are meant to be, if you know deep in your bones that your one precious life is lovely and worth living — then you’ll storm the castles of your life and set the world ablaze.”

Timothy Shriver has been a regular visitor to his Kennedy relatives’ houses on the South Fork over the years.

Sally Susman lives in Manhattan and Sag Harbor.