Prayers and Exploding Plastics

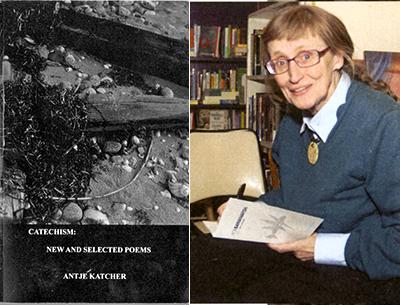

“Catechism”

Antje Katcher

Three Mile Harbor Press, $15

And I pray that I may forget

These matters that with myself I too much discuss

Too much explain

Because I do not hope to turn again . . .

— “Ash-Wednesday,”

T.S. Eliot

“Catechism” is a collection of poetry by Antje Katcher, posthumously selected by the poet’s publisher, Paul Genega of Three Mile Harbor Press. It is a collection full of ceremony — a biblical, mythological, and personal tribute to Ms. Katcher’s greater body of artistic work. After a career as a financial analyst, she translated business documents from German to English. It is her poetry, however, that we remember her by today.

Ms. Katcher wrote under the influence of liturgical teaching and seemed to inherit the wind of its philosophical underpinnings and ineffable proofs. She blends themes from the Judeo-Christian tradition with motifs from other world religions, while examining familiar refrains and quoting popular prayers. Complex theological arguments get parsed in deft tercets. Elegiac stanzas question the reality of God’s existence. The literal origins of faith receive the full treatment.

Your kingdom come!

What does it mean? Beware of what you ask —

There is blood in the wine

Raptures and virgins, grapes and mustard seeds,

Prayers and exploding plastics, everywhere they cry:

Your kingdom come!

And in the name of the all merciful

This is the day of judgment!

There is blood in the wine

Or are we simply blind

Looking for signs and miracles while praying

Your kingdom will come

When it is here — if we would but let it emerge

Among — within — us would there still

Be blood in the wine?

These are lines from “Catechism,” the book’s title poem. As you can see, poets do not always play nice with their epistemology, and Ms. Katcher does much to keep her work from turning into paroxysm. It’s as if there were no honest way to fully unpack a prayer without getting a bit down and earthly. Her textual analysis and biblical references become their own form of artistic worship, sourced from a wordless beyond to remind us that raptures and virgins, prayers and exploding plastics really do have something in common.

“Catechism,” the collection, consists of three sections, and by the end of Part I, our poet yearns to return to the things of this world. Part II starts to sing about a more earthly apotheosis: to be devoured, consumed, enjoined with life as we know it. Wouldn’t you like to feel the bliss of a blessed union, rather than merely contemplate it? Ms. Katcher shines when she breaks from theology and roots her language in the familiar. Her lines take on a breathlessness, urging without pause to address the flesh:

Yes, even that would be better, even pain

and bleeding if it was felt by my body

as mine — far better than eternal numbness

endless captivity within these thoughts . . .

In “Ophelia Incarnated Addresses the Bard,” the hesitancy to leave the known, to depart for something potentially greater, has been abandoned. As strange as it may be to have a body, the poem serves to answer the madness of ambivalence, whether it be personal or religious in origin.

Part II of the collection dives into gods, myths, and ancestors, calling out the overlords in unselfconscious tones. The poet recalls her grandfather with touching clarity, and fearlessly asserts her own self in “Cherries,” a poem about her mother and grandmother.

. . . for once we’re at one,

hands stained with bloodblack fruit

passing cups to each other

cherries and pits, to fill and empty

pitting with the same rhythm

when the old woman reaches out

makes me earrings out of twin cherries

laughs softly just for a moment

and the cool under my earlobes

suddenly makes me feel grand

like a painted lady.

Part II of “Catechism” is richer, melodic, comfortable with juxtapositions of heaven and earth. Ms. Katcher writes about the Frisian Islands, and other “bright yellow islands,” as if liberated from the futile dilemma of what is holy. Things finally just happen, without the overwrought need for explanations. Her work finds splendor in what exists, as opposed to the disengaged torment of what may be, and establishes a deeper, more peaceful abode.

It’s as if the struggle to comprehend religion is somehow inherited, for when the poet abandons it, she produces her most peacefully vivid work. As dogma is rejected, the disquiet fades, and Part II of “Catechism” embraces the way things are in nature. The mood shifts entirely, from query to tranquillity. The sonority of the poems at this point is startling:

Let us sail south, fish

for the moon among the islands, find a

beach and in the shadow of banana

trees build ourselves a fire . . .

— then wonder why bananas

are yellow, answer ourselves because they are bananas

ask no further questions of the day.

Everything, I promise, will be perfect . . .

“A Perfect Day for Bananafish” is one of the best poems in the collection because of its confidence and timely prescription for happiness. Here there is no doubt about what to say or do. The poem sets up Part III of “Catechism” with a careful, nuanced bravado that is wholly welcome. The third part of the book delves further into personal history and creates a fairy tale-like atmosphere. Ms. Katcher explores memories with an idealistic eye and occasionally reverts to the platitudes of scripture for context.

The closing poems riff on literary and historical figures, narrative pieces that lack the breadth of emotion contained in the more lyrical second section. The themes do not develop beyond the occasional vision of something more luminous, and echo the sense of an intellectual anguish quenched only by reality, something the poet Wallace Stevens also grappled with.

“Catechism” is a work of some irony: a poet who appeared to be unsure of her place in the world and looked elsewhere for acceptance. Yet her best writing says it all; clearly her home was here, all along.

Antje Katcher’s poems appeared in journals and magazines including Calyx and New York Quarterly. She was a resident of Springs and died in 2014.

Lucas Hunt, formerly of Springs, is the author of the poetry collections “Lives,” “Light on the Concrete,” and the forthcoming “The Muse Demanded Lyrics.” He is the director of Orchard Literary and the founder of Hunt & Light, a publisher of poetry.