The Prose King

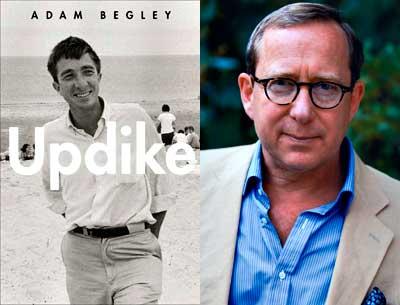

“Updike”

Adam Begley

Harper, $29.99

John Updike was, undoubtedly, one of the most gifted American prose stylists of the 20th century. And also one of its most prolific. Along with over 20 novels, Updike published countless short-story collections, poems, essays, reviews, and assorted miscellanea, most of it appearing in The New Yorker, with which the author had a roughly 50-year relationship.

He has been attacked, variously, as a misogynist, a political hawk, and (most stingingly to the author) as superficial. But no one has ever adequately impugned Updike as a writer of sentences. Who would dare? His prose danced, pirouetted, scissored, and often threw off sparks of erotic lyricism. In the thousands of pages that he produced, it would be a fool’s task to look for a dull sentence. I imagine there’s probably one in there. Somewhere. But good luck with that.

Still, who was he? In his new biography, “Updike,” Adam Begley sets to find out. It is, at times, a yeoman’s task. John Updike’s life did not manifest the dramatic trajectories of many of his contemporaries. There was no military service, alcoholism, financial destitution, concealed homosexuality, or racial injustices. There are no overlooked masterpieces or debilitating depressions. This is good news for Updike and a dearth of nourishment for a prospective biographer. Five hundred pages with a subject who views his major vice as an abiding obsession with golf? “Even his neuroses were tame,” the biographer admits. Mr. Begley has his work cut out to keep us engaged.

We begin in Shillington, Pa., where an archetypal American boyhood has its painful interruptions. There was a stutter, developed at the age of 6, which Updike never completely dispelled. More traumatic were the persistent attacks of psoriasis that forever haunted him: “red spots, ripening into silvery scabs,” as Updike described. Not all is lost, however: In his memoir, “Self-Consciousness,” Updike directly credits the scourge for turning a mirror upon himself, for making him hyper-aware of the world and his place in it. In other words, for making him a writer.

Home life on a Pennsylvania farm was classic Americana, with complications. There is the author’s mother, who was apparently “prone to anger.” Though the ire was not aimed directly at John, the home front was occasionally tumultuous. As Mr. Begley writes, “There was quarreling, ‘smoldering remarks,’ and the slamming of doors, an atmosphere of barely suppressed rage.” John also felt isolated on the farm, spending an inordinate amount of time alone. Still, the young writer thrives, selling his first poem to a magazine at age 16 and graduating co-valedictorian.

Off to college he goes, though not without what Updike himself described as the “shock of Harvard.” He felt provincial and out of place in the Ivy League, though he thrived academically. He was Phi Beta Kappa by his junior year and wrote for the prestigious Lampoon, often putting the entire magazine together himself.

Socially, though, things were more challenging. “Almost everyone who knew Updike at the time stressed that he was different — a little odd, and certainly not a mainstream Harvard type.” Young John possessed neither money nor “class,” though once again he turned the negative to his creative advantage. His outsider status honed his powers of perception, and it can be argued that a lifetime connection to provincial America gave him access to his greatest invention: Rabbit Angstrom.

Updike moves on to postgrad work at Oxford, after which he gets a meeting with the legendary New Yorker editor William Shawn, who is impressed with his work from the Lampoon. John is hired, of course, and so begins a relationship that lasted for the next half-century.

“It is worth pausing here to marvel,” writes Mr. Begley, “at the unrelieved smoothness of his professional path.” Marvel may be an understatement. Once in Manhattan, Updike even manages to find the perfect publisher for his fiction, Knopf, where the editors are gentle with him after the merely modest success of his first three novels, “Poorhouse Fair,” “The Centaur,” and “Rabbit, Run.” This was certainly a kinder era in publishing, but also a testament to the kind of patience Updike’s talent could exact. Knopf recognized the gift and its potential to ignite. And ignite it did, in 1968, with “Couples.”

As with Harvard, Updike felt out of place in Manhattan (the “New York smarties” he once called them), and by the end of the 1950s he had settled in Ipswich, Mass. It is there that the novelist met head-on the suburban version of the Swinging Sixties. The “Ipswich Gang,” as Mr. Begley calls them, were a group of young, attractive professionals living in what Updike famously named the “post-pill paradise” of the Kennedy era. It is probably the only period of real tumult in Updike’s life, and like a famished lion, Mr. Begley is all over it. He writes of Updike that he “threw himself into the tangle of Ipswich infidelities.”

Interestingly, the biographer hints that it may have been the author’s wife, Mary, who was the first to succumb. “In the early sixties she took a lover; asked whether her affair, which lasted several years, began before or after John’s first fling, she said she didn’t know.” In any event, these years gave Updike the milieu for “Couples,” which went on to sell over four million copies. It also provided the writer an endless trove of erotic material that he mined for the remainder of his life.

What follows is one of the most fecund periods in American literature, with Updike producing nearly a book a year for the next two decades. Included in this are three more in the Rabbit series (two of which won the Pulitzer Prize), “The Witches of Eastwick,” “Roger’s Version,” and a constant stream of estimable short stories, many of which were published in The New Yorker.

Congruent to these years is the appearance of Martha Bernhard, an Ipswich neighbor whom Updike married in the late 1970s after his divorce from Mary. While it might be too much to call Martha the villain of “Updike,” John’s friends from Ipswich took a particularly toxic view of her. “A chorus of neighbors,” Mr. Begley writes, “. . . testified that Martha ‘went after’ John with a single-minded resolve readily apparent to all.” Soon after, the new couple moved away from Ipswich, cutting themselves off from the “old gang” with a stunning finality. And Martha’s rigid restrictions on visitations did not endear her to John’s children with Mary either.

Oddly, Mr. Begley takes great pains to defend Martha, reminding us of John and Mary’s role in the divorce, and John’s own willingness to dismiss his old friends. Ultimately, though, the biographer’s language begins to strain in her defense: “The tough and fearless Martha was conspicuously purposeful, unhesitatingly vocal, and perfectly willing to bully John for his own good.” Okay then.

As good as John Updike was, there can be no question that the final novels are not among his best. “Toward the End of Time,” “Gertrude and Claudius,” and “Villages” showed a diminution not so much of talent as material — having exhausted his exploration of suburban America and its strained relation to God, the author seemed incapable of finding a new anchor for his sentences.

The critics, who had been mostly kind to him, had the taste of blood in their teeth. “Of course it is ‘beautifully written,’ ” James Wood said of “Toward the End of Time,” “if by that one means a harmless puffy lyricism.” It is also, he wrote, “astonishingly misogynistic.” Reviewing the same book, David Foster Wallace accused Updike of being a parody of his former self, and finally even of “senescence,” a judgment that Mr. Begley rightly calls out as “sadistic.” After 50 years, they finally had Updike cornered. Some fun, I suppose, was had.

And yet, even with a mediocre final act, the literary career of John Updike was one of the greatest of the last century. Is it a little surprising, then, that the life of such a man can be covered in just 486 pages, and that even then “Updike” feels a little long? If so, one can hardly fault Mr. Begley; he is brave to take on such an essential, though ultimately static, subject. “Updike” is both convincing and well researched, and when the dramatic details of the life lag, as they often do, the biographer fills in with literary analysis that is genuinely illuminating.

I’m not sure how Mr. Begley could have done any better, though it might do well to call “Updike” the definitive biography and be done with it. There hardly seems need for another.

Kurt Wenzel’s novels include “Lit Life” and, most recently, “Exposure.” He lives in Springs.

Adam Begley, a former reporter for The Star, is a regular visitor to Sagaponack, where his parents have a house.

John Updike died in 2009.