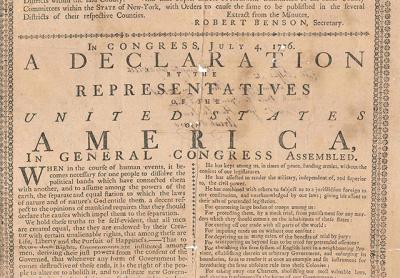

Rare 1776 Declaration With East Hampton Provenance

A copy of the 1776 Declaration of Independence that was passed down through descendants of Col. David Mulford, an East Hampton man who led a regiment at the time of the American Revolution, is about as rare a document related to the birth of the United States as is known.

Out of an edition of 500 printed by John Holt on July 9, 1776, in White Plains, only 5 copies are thought to have survived. It will be sold at auction, along with a collection of early papers related to the history of East Hampton, on Saturday by Blanchard’s Auction Service in Potsdam, N.Y.

Blanchard’s has set a pre-auction estimate of $500,000 to $1 million for Colonel Mulford’s Declaration and between $25,000 and $50,000 for the family papers.

In a catalog prepared for the auction, the auction house described the contemporary owner of the Declaration and the other papers as a descendant of Colonel Mulford, as well of members of the Gardiner and Buell families. Lion Gardiner, who died in 1663, was the first European landholder in what would become New York State. His daughter, Elizabeth, born on Gardiner’s Island in 1641, was the first child of English parentage. Colonel Mulford was born in East Hampton in 1722 and died here of smallpox in 1778.

The collection of papers to be auctioned on Saturday includes items that provide insight into the daily lives of women and enslaved Africans, something conspicuously absent otherwise from the historical record.

Kip Blanchard, who runs the auction house with his wife, Sue, said that he first saw the papers and the Declaration about eight years ago in a desk drawer where they had been stored. Their condition was excellent, he said, since they had been kept in a clean, dry place and only rarely exposed to light. At the time, there was no plan to sell them.

However, in 2015, the upstate owner, who decided to remain unidentified, saw a news story about curators at the Cincinnati Museum having discovered a Holt printing of the Declaration of Independence in its collection. That got things moving, and the owner asked the Blanchards earlier this year if they would sell it and the other papers.

Mr. Blanchard turned to Keith Arbour, a manuscript and printing specialist in Cambridge, Mass., for authentication and to help understand the significance of the Declaration and the associated family papers.

“This is a copy that descended in the most ideal way. It’s really a historian’s dream, preserving all the context,” Mr. Arbour said in an interview.

Mr. Blanchard said setting a pre-auction estimate was difficult. None of the other four known Holt printings of the Declaration has ever come up for sale. A copy of the first broadside printing of the Declaration of Independence, by John Dunlap in Philadelphia on the night of July 4, 1776, sold for more than $8.1 million in 2000.

The Holt edition came just five days after Dunlap, the official printer of the Continental Congress, made his 500 copies. Presumably, Mr. Blanchard said, one of the Dunlap broadsides was rushed by horseback to the Provincial Convention of the Colony of New York and then to John Holt, who set it in type, making some minor changes to punctuation and how some words were capitalized. Holt’s Declaration is less a second printing than a nearly contemporaneous version, issued with the same intent: to get the word out as fast as possible about the revolutionary cause.

As a preface to the Holt edition, the New York delegates unanimously resolved that they would “at the risque of our Lives and Fortunes, join with the other Colonies in supporting it.” They then gave orders to print the Declaration and “publish the same with the Beat of Drum, at this place on Thursday next.”

It was a dangerous act. Mr. Blanchard said that possessing a single copy of the Declaration would result in death if one of the revolutionaries were captured by the British.

“We tend to think of the people in 1776 as already radicalized, but most people were not in favor of independence,” Mr. Arbour said.

David Mulford’s copy reached him within days of coming off Holt’s press. The Declaration passed through Uriah Rogers’s hands in Southampton on July 24, 1776, according to a notation on the letter that contained it. Rogers had been a major in Colonel Mulford’s regiment, and wrote that he had “made Bold to Open & Read them.”

“It’s a rally-the-troops message, and it’s stunning, really,” Mr. Arbour said. Many colonists at that time were undecided, and many admired King George. “It’s a pretty shocking thing to bring these charges against him.”

“It’s a weapon, a live, legal document. It says, ‘Detach yourself from the king and put yourself under the protection of the United States of America,’ ” Mr. Arbour said.

By that point, Mulford had been a member of the local militia since at least 1748. By March 1776, according to his report to the Provincial Congress, he commanded 768 men. His regiment was en route to Brooklyn in August of that year, when the British routed the American Continental Army. Mulford’s regiment was ordered to turn back and ready themselves to fight another day.

Over the years, the Mulford copy was rarely seen. Among other items to be auctioned Saturday are an 1895 news clipping from The Mount Vernon Daily Argus reporting that Robert L. Mulford of Second Avenue had put it on display between two pieces of glass.

“To think that the Library of Congress does not even have a copy of this,” Mr. Blanchard mused.

The second lot in the auction, with its collections of wills, letters, and broadsides, is of interest to historians as well. One item is a 1667 description of local Indian tribes by Thomas James, who was East Hampton’s first minister. Another is an original 1716 printing of Samuel Mulford’s defense of East Hampton residents’ right to catch whales from the beach without taxation by the British crown.

“To me, the importance of the documents is how vibrant our community was in the late-18th and early-19th century, how very cosmopolitan we were,” Richard Barons of the East Hampton Historical Society said. “This was a young, enthusiastic community, interested in the Revolution, in investments, in many things,” he said.

Other items include broadsides reminding would-be rebels that it was not too late to return to the king’s cause. A 1777 proclamation outlines terms for pardons and protection of those who might surrender within a set period of time. Mr. Arbour said that judging from the relative absence of wear and tear the pro-British material in the collection appeared to have been tucked away almost as soon as it was received.

An appraisal from 1798 of the estate of the Rev. Dr. Samuel Buell, who was East Hampton’s minister before and after the Revolution, listed among his goods a wampum belt and four African slaves with remaining years of service.

In a 1799 will in the collection, Mary Gardiner, the widow of Col. Abraham Gardiner, leaves to her son Nathaniel “my clock, my mill, my sword which was his Fathers, my new Silver Cann, one half dozen spoons marked AMG, one black walnut chest.” Those items in a later will found among the papers instead were to go to a grandson.

Another item, a letter written in 1796, is to Colonel Mulford from John McComb, the architect of the Montauk Lighthouse.

Also dating from 1776 is a bill of sale between David Mulford the younger and Reverend Buell for “my Negro Servant man called Gree.” The price, “fifty pounds of lawful money of New-York currency.”

Other letters convey detailed military intelligence or hint at disagreements among men over their degree of commitment to the revolutionary cause.

Among the familiar old East Hampton names are some that are not so well known. One is in a 1759 indenture agreement for Benjamin Pinick of “Montauket on Long Island,” who went to work on the Isle of Wight, the name of Gardiner’s Island at the time.

The auction will take place at 11 a.m. Saturday. Blanchard’s plans a live-stream of the proceedings and a short introduction to the lots by Mr. Arbour.

Mr. Barons is hopeful that the family papers, Lot B in the Saturday auction, can return to East Hampton. The East Hampton Library is among the parties interested in bidding for them to add to its climate-controlled Long Island Collection. “It would be so much more readily available to have them in this community. It means that they can become woven in as part of our whole fabric,” Mr. Barons said.