Reinventing Comics

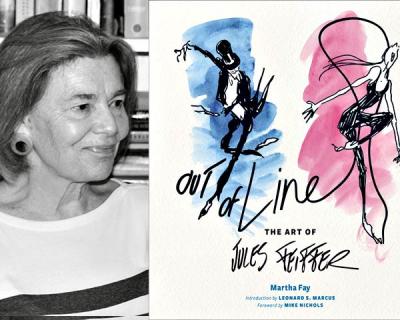

“Out of Line: The Art

Of Jules Feiffer”

Martha Fay

Abrams, $40

One of the most incisive Jules Feiffer quotes Martha Fay uses in this generously illustrated biography gets to the core of the artist’s culture-shaking genius:

“I wanted to put the essence of my reader on the page . . . to move him out of his genteel, benign, suburban WASP landscape. I wanted to circumcise the sucker and transplant him from the Jazz Age from whence he came to the Age of Anxiety, from Babbittry and Dale Carnegie to Sigmund Freud. . . .”

Mr. Feiffer was talking specifically about the ’60s and his strip “Sick, Sick, Sick” in The Village Voice, but the combination of societal insight and creative aggression reflected in his remark has been the booster rocket of all his work and why, for more than 50 years, we have hung on the fence of his deconstruction site watching the work of this nervy kid who can say the things we wouldn’t dare and probably couldn’t think of in any case.

The hard cover underneath the dust jacket of “Out of Line” is a facsimile reproduction of Mr. Feiffer’s art class binder. It is an endearingly clunky lettering job spelling out JULES FEIFFER ART 330 SEC. 5.14 along with a determined drawing of a palette and brush. In faint pencil lines all over the cover are Jules’s doodles of superheroes, boxers, and math computations. In the drawings’ obvious fervor in which the young Jules proclaims himself an artist and its establishment of two of Mr. Feiffer’s main themes (minus the math), the cover sets up the charming and witty tone of the whole book.

The first chapters show drawings Jules’s mother saved from his childhood and the family photographs from the same period. The drawings, youthful as they are, establish an attitude, vigorous and pugnacious, that we can recognize in Mr. Feiffer’s early comics, the breakthrough strips in The Village Voice, and even the plots of his plays and movies that followed. That’s one of the things the many illustrations in the book establish, that with all of the false starts, the moving into new territory, the experiments with style, there is a core confidence in Mr. Feiffer that never really wavers.

Ms. Fay’s fluid and urbane writing gives the sociological context that the story needs given how much Mr. Feiffer was reacting to the times, and she uses quotes from Mike Nichols, Hugh Hefner, Ed Koren, and this one from Art Spiegelman to reflect Mr. Feiffer’s relationship to his peers: “That’s what made Jules so significant and a real role model. He had to reinvent comics to take advantage of his subjectivity, his . . . intellectual side.”

In revisiting the many Village Voice strips reproduced in the book I was struck by how time-defyingly brilliant they are. The characters he invented seem like friends from my youth whose anxieties and pretensions are forever current — the modern dancer celebrating spring and her personal angst; Bernard, the nebbish, agonizing over the meaning of manhood and his failure with women; Huey, the cad, who succeeds where Bernard fails.

Then, of course, the parade of politicians whose words Mr. Feiffer unmasks for the manipulative dissimulations they are. The strip in which President Kennedy checks in with his press secretary for polling on his popularity, for instance, reveals the hungry ego behind the heroic facade. Mr. Feiffer lets Nixon, sitting, stolidly staring out at us, speak for himself in strip after devastating strip. Mr. Feiffer’s satirical provocations probably had the same impact on the young in the ’60s and ’70s as Jon Stewart and “The Daily Show” has had in our time.

Intermittently, during these years of writing and drawing “Sick, Sick, Sick,” Mr. Feiffer had been writing plays, “Little Murders” and “Knock, Knock,” among others, and screenplays, “Munro,” “Carnal Knowledge,” “Popeye,” and “VD Blues.” The stories that Ms. Fay tells of the writing and producing of these plays and films are the most celebrity-filled parts of the book and, along with the popular triumphs of these productions, describe Mr. Feiffer’s difficulties with some of his collaborators and with the critics of the work. Walter Kerr, for instance, first put down “Little Murders” as being “the funniest of Mr. Feiffer’s jaundiced visions,” before seeing it again and giving it his big thumbs-up.

Ms. Fay’s story of Mr. Feiffer’s experience writing the script for the movie “Popeye” is the classic literary writer’s story of being chewed up in the maw of a big Hollywood production, but Mr. Feiffer’s candidness in revealing his interaction with and his feelings about the director Robert Altman give the tale a vividness you don’t usually get in these movie recollections.

Although Mr. Feiffer had illustrated Norton Juster’s “The Phantom Tollbooth,” the real beginning of his children’s book period began with the creation of “The Man in the Ceiling” in 1993. It started as a failed collaboration with his longtime friend Edward Sorel, Mr. Feiffer to write the story and Mr. Sorel to illustrate it. When Mr. Sorel backed out, feeling the gist of the tale wasn’t right for him, Mr. Feiffer decided to proceed and illustrate it himself. The picture book form released a different kind of fictional writing in him that was immensely pleasurable, led to his doing 10 more books for children, and, in a way, prepared him to embark on the most significant book of his current career.

“Kill My Mother,” a graphic novel, to which Ms. Fay devotes the last 11 pages of the book, is an extraordinary achievement and, as Ms. Fay writes, “might be said to bring [Mr. Feiffer’s] long run full circle.” The novel is a complex story involving all Mr. Feiffer’s favorite noir set pieces from 1940s movies: the tough detective, the mysterious dame, meetings under lamp light, and even a scene in the World War II Pacific jungles with a transgender soldier (Jules, you got ahead of the zeitgeist, again!).

As ingenious as the story is and as satisfying the zing of the dialogue, the art, it seems to me, is an even more astonishing accomplishment. Sixty-three years after the young Jules Feiffer struggled unsuccessfully to match the smooth complexity of Will Eisner’s style in “The Spirit,” the 84-year-old Feiffer broke through to his own way of drawing and painting a much more complex story than he had ever tackled. The rapid, impatient Feiffer line still gets to the essence quickly, but now the artist can use it to describe extremely nuanced body language and the interaction of many figures in a scene. Where once color in his work was a secondary handmaiden to the line, it now becomes a major element, evoking light, atmosphere, and psychology. Whole scenes are dominated by the mood of what the color washes and intricacies set up. I can only imagine the bliss he felt while working on this book.

“Out of Line” is a fascinating visual and literary journey through the multifaceted life and work of a creative icon of our times. The book couldn’t have had a more satisfying ending than to document Jules Feiffer stepping up to the plate once again and, with “Kill My Mother,” hitting an artistic home run.

James McMullan, formerly of Sag Harbor, has painted scores of posters for Lincoln Center Theater and illustrated many children’s books with his wife, the writer Kate McMullan. His latest book is “Leaving China: An Artist Paints His World War II Childhood.”

Jules Feiffer lives in East Hampton.