Richmond Burton: Yin and Yang

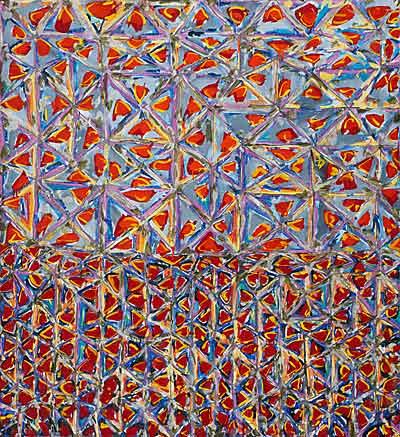

Richmond Burton likes to paint big, unless he wants to paint small. He uses oil paints applied so thinly they appear matte, sometimes translucent, and a lot more like acrylic. He is a trained architect who prefers mark-making in a two-dimensional form, and he really likes color, but sometimes he does not. His work over the past two decades has shown a dance across the spectrum of rigid systems of grids and complete abandonment of that structure for more organic abstraction.

There are a lot of contradictions here, and it seems to suit the artist, who lived in East Hampton, in Elaine de Kooning’s old studio, from 1998 to 2011. The work he left behind when he moved to Los Angeles and then Woodstock is the subject of an exhibition at Silas Marder Gallery in Bridgehampton, organized by Jess Frost.

Although there have been many times that the art on the walls of the old barn structure, with a gently peaked arch roof and ceiling, has looked as if it were made for the space, here it is even more so. The brightly hued paintings look like stained glass windows in a Romanesque church, and Ms. Frost used the installation to highlight that effect. The artist even calls some of his paintings “windows,” so it is not off the mark to see them as such. Veils and chalices are some of the other associations brought up by the paintings, but those are more fanciful.

At floor level on a side wall, there are two large, almost square, works from 2010 titled “Architecture,” one red, one yellow. They are big, beautiful, and bodacious, the red gridwork on the one highlighting the jewel tones within it and the yellow and white of the other gently obscuring them. They are works that sum up much of the push-pull, yin and yang of Mr. Burton’s oeuvre.

On the back wall are four “Stretch Paintings‚” each named for its predominant color: green, yellow, orange, or red. Looking like netting that has captured the brightest and most colorful jewels, they are pulled and pinched just once in the center and placed against a pewter background, painted on old cheap plywood doors. What an elegant way to dress up a rather unattractive architectural element, and a perfect way to reintroduce an element of one’s background into one’s current practice.

These are all rather large works. Upstairs, it is more of a mix of intimate panels and more expansive compositions, along with some paintings made in Los Angeles and Woodstock. The spot that might be occupied by the rose window in a traditional church is taken up by the last painting made in East Hampton.

“Elevator‚” from 2011, has been raised high on the back wall of the loft and is visible at ground level in a way that allows it to play with all of the other paintings in the gallery. It is dark and bright at the same time. The kaleidoscopic grid is there but obscured, not by blackness but by a deep, dark navy. It hints at sadness and ending but underscores the exuberant beauty underneath. The painting succeeds in capturing what it would be like to be melancholy in a place as rich in natural wonder as the East End.

Although it was not the painter’s intent, in this context, which evokes church windows, the deep blue is celestial and melds nicely with the allusions to the color of Mary’s garments in traditional Christian painting, which are intended to symbolize the sky and heaven.

The Los Angeles paintings, all easel-sized, have lighter and brighter grids, showing the warm western light filtering into his working method. “Horizon Window — Orange and Red,” a work from 2013 painted at Woodstock, returns to a cooler palette and a larger format.

Everyone seems to have a favorite artist to compare Mr. Burton to, and why not. As Sheridan Sansegundo pointed out in a Star profile of him in 2005, he is from “the generation of appropriationists.” There is Frank Stella, Pat Stier, even Gustav Klimt — but Mr. Burton retains his own vision from unique experiences that seem much more influential than just art on a wall.

The exhibition will remain on view through Aug. 11.