Riddle Me This

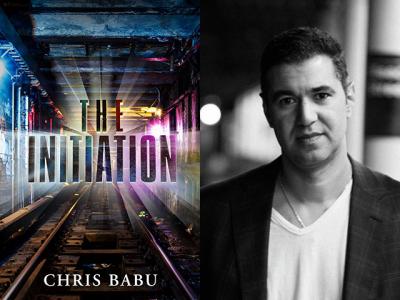

“The Initiation”

Chris Babu

Permuted Press, $21

Is it a dream or is it a nightmare? You have the run of the Manhattan subway system, from 72nd Street to the South Ferry station. No crowds. Save for that section carpeted with hundreds of thousands of rats you have to sprint through as they crunch underfoot, “screeching and squealing . . . a warm, jittery pile of fur and bones . . . like standing on a deflated basketball.”

That’s just one of a host of tests facing six teens foolish or desperate enough to enter the subterranean Initiation in Chris Babu’s debut novel for young adults, a dark vision of a New America, hardly a nation, really, rather a city-state sealed off from the disease-ravaged wastes beyond its walls, depleted in numbers, severely rationed, technologically primitive, plagued by blackouts, and constrained by a strict caste system broken down by job skills. Citizens are even confined to neighborhoods with their own kind — the Dorms, home of “the working stiffs,” the Lab, with scientists, doctors, those with technical expertise, the Precinct, for a security force, called the Guardians, out of all proportion to the population, and the Palace, where reside the ruling elites and their seconds.

Human civilization has been brought low by the events of the Confluence: a worldwide cyberterrorist attack, the Inequality Riots sparked by advancements in tech and automation and the attendant mass unemployment and surging corporate profits, a subsequently mishandled recession, and a superbug outbreak.

It’s not for everyone. But for many readers, those with childhood comic-book backgrounds, for instance, portrayals of the crippling of society are enjoyable, to say nothing of the useful reminder of how close we are to the cliff. Science fiction, fantasy, speculative fiction, dystopian fiction — there’s usually a tradeoff. Frank Herbert’s dialogue and characters may have ranged from wooden to particleboard, but that was one heck of a world he envisioned in “Dune.” (For one example.) The sheer imagination can be impressive.

“The Initiation” is indeed dystopian, mining a healthy if jaundiced tradition marked by Paul Theroux’s post-nuclear “O-Zone,” from 1986, on up to, of course, “The Hunger Games.” Here, for the young, namely 16-year-olds done with their schooling and facing a lifetime of drudgery in predetermined occupations, the way out is the Initiation, but the price of failure is exile, a sure death, outside New America’s walls. It’s been eight years since anyone survived the gauntlet.

The difference in this case is that the author has a degree in mathematics from M.I.T. He likes puzzles, brainteasers, questions of logic, tests of deductive reasoning, and these are thrown in the path of the tunnel-scurrying teens repeatedly. Drayden, the protagonist, and his fellow brainiac among the “pledges,” a quiet, inward-focused girl named Catrice, lead the way as mental gymnastics trump muscle.

Catrice is every bit Drayden’s equal, and promptly solves the second question they come across, one sure to enrage or intrigue the Y.A. crowd, depending on past experience with those word problems from middle school math class: “The larger hourglass measures eleven minutes, while the smaller measures seven minutes. You must measure exactly fifteen minutes using only the two hourglasses.”

Good luck.

True, the Bureau of New America, as the sadistic overlords are called, is selecting for intelligence first and foremost, but also for bravery, which, as Drayden’s favorite teacher had it, “while often dormant, existed in everyone.” This is tested by way of physical challenges probing a hit parade of fears — heights, claustrophobia, drowning, cockroaches.

Mr. Babu may not be J.G. Ballard, but then who is? For teens he successfully puts into play all manner of concerns, from bullying to catty competition among girls to petty jealousies and insecurities to betrayal and resentment to who likes whom.

And if there are life lessons along the way, so much the better. Here’s one: “We all start with an equal shot!” Drayden shouts in frustration at his acquisitive but unworthy former friend. “Like the kids in class who goofed off and failed without trying, and whined when they received crappy job assignments,” he thinks to himself. “At a minimum you had to exert yourself, to put in the work.”

Chris Babu lives part time in Southampton.