The Rise of the Right

“We Gather Together”

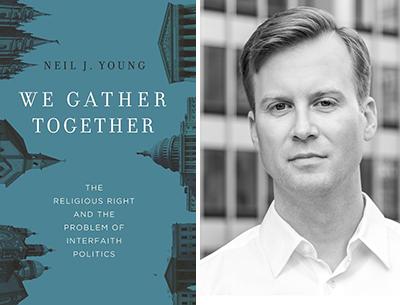

Neil J. Young

Oxford University Press, $34.95

Especially in a presidential election year such as this one, it is timely and interesting to delve into the backgrounds of the forces that are shaping the political scene. Neil J. Young has given us a detailed and thought-provoking history of one of those movements in “We Gather Together: The Religious Right and the Problem of Interfaith Politics.”

Mr. Young, who has taught at Princeton University, did a doctoral dissertation at Columbia University that looked at the religious right from 1972 to 1984. He knew intuitively that there was much more to the story, and this led him to greatly expand and revise his dissertation into the book.

“We Gather Together” shows that, contrary to popular thought, the religious right did not suddenly rise up as a unified group in the 1970s in response to Roe v. Wade, the Equal Rights Amendment, or similar developments. Rather, he goes back to the 1950s, when there was a liberal ecumenical movement growing among mainline Protestants and liberal Jews, and shows that Catholics, Mormons, and evangelicals cautiously formed alliances to resist it, even though they viewed one another with great suspicion and animosity.

The religious right is often seen as a monolithic group, and it certainly gives that impression in the political arena. But although it was brought together by cultural and political concerns, from the very beginning the coalition has been beset by problems, has been fragile, contentious, and even combatant, with huge theological and religious differences.

The terms evangelical and fundamentalist are often used interchangeably, and indeed there is some overlap. Mr. Young defines fundamentalists as being more conservative and much more separatist. Evangelicals, on the other hand, put themselves between fundamentalists and the liberal ecumenical movement, and have been more willing to work with each other, at least on cultural and political causes, even while they disagree on theology.

The role of Mormons has been mentioned by others but has not been closely examined. Mr. Young is perhaps the first to put them at the center of the story, because in fact they have been prominent players in the religious right since the 1950s.

From the myriad examples of how the uneasy relationships among the various groups became a unified front, I will recount some of the story about Phyllis Schlafly, remembered for her work against the Equal Rights Amendment and against legalized abortion in the 1970s. She saw the E.R.A. as a cause to bring together conservatives, especially women, who believed the amendment would attack marriage and the roles of men and women as they were traditionally understood.

What may not be so well remembered is that Ms. Schlafly was a Catholic from Illinois, and at first these issues were seen by others as largely Catholic issues. Some evangelical leaders and publications were speaking against the legalization of abortion, notably Christianity Today, the magazine founded by the evangelist Billy Graham in the 1950s. However, many lay evangelicals and clergy were ambivalent toward the issue, for fear of being identified too closely with Catholicism.

In a highly unusual move, Ms. Schlafly became the first Catholic invited to speak from the pulpit of the televangelist Jerry Falwell at his Thomas Road Baptist Church, where she gave a talk on the E.R.A. At about the same time, the Mormon Brigham Young University also invited Ms. Schlafly to give a similar speech on the same subject; it was an extremely rare appearance of a Catholic at a Mormon institution. These were two events that seemed to show a unity between the various groups and helped to push the movement into the forefront.

But Mr. Falwell once revealed a good bit of truth as he quipped to a reporter, “When Mormons, Catholics, Jews, and Protestants come together you’d have a bloodbath if it weren’t political. We’re willing to fight for a common cause, so we can fight with each other later.” Though he was being somewhat tongue-in-cheek, he was referring to a deep-seated fear of each group that the others would eventually grow large or powerful enough to overrun the rest.

Other areas covered in the book include the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, the complex subject of school prayer, the Moral Majority, the surge of growth in the Mormon Church, and the religious right’s relationship with President Reagan.

“We Gather Together” has put a spotlight on the religious right, in order to help us understand more deeply one of the forces shaping our national scene today. I would like to see a similar look at the liberal ecumenical movement, which was originally the catalyst for the religious right. It seems that this group, which comes together in national political effort, is a major but often overlooked force today.

At the same time, the narrative shows that while various leaders often come together on national issues, there is a disconnect because the laity is actually quite varied and diversified. Apropos the current political scene, Mr. Young has said in an interview elsewhere that while most evangelical leaders actively oppose Donald Trump’s candidacy, he is supported by large numbers of evangelical voters.

Mr. Young concludes that the religious right will continue in much the same way, its members working together on shared political goals, but also having very deep commitments to their own brand of theology and quite literally working to convert each other.

“We Gather Together” has a scholarly bent. It quotes extensively from various books, magazines, documents, memos, and speeches, and there are some 90 pages of notes. Considering the wide scope of the material and its historical value, perhaps an index would have been a helpful tool.

With this attention to detail, Mr. Young not only weaves a strong and convincing narrative, but many of the personalities and events come alive. “We Gather Together” is a very fine read for those seeking to add great depth and many dimensions to their perspective of the religious right and how it shapes today’s political stage.

Thomas Bohlert, a music and book reviewer for The Star, lives in Springs.

Neil J. Young has a house in East Hampton.