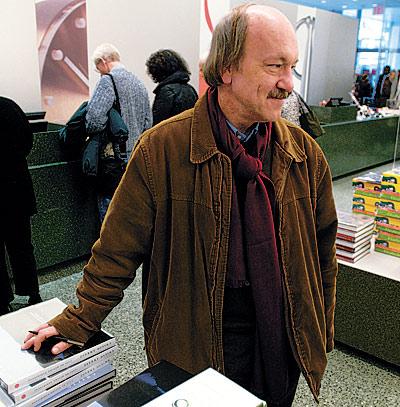

Robert Long: Image and Insight

Making claims about the importance of recently deceased poets is a tricky business, especially if the poet was a friend. Robert Long, who died in 2006, was a friend, a poet friend — and friendships among poets is a subject worthy of its own treatise — and therefore it’s probably impossible for me to attempt to be objective about his work without sounding self-serving or distorted by that perverse calculus of grief and identification. But I can say that it continues to surprise and delight me and that I therefore feel entitled to claim, by my own personal standards, that it’s both original and serendipitously blunt. I like bluntness, especially the indirect, somewhat back-stepping kind. In other words, Frank O’Hara and E.E. Cummings’s kind.

Robert Long wrote one full book and what amounts to three chapbooks that were filtered into the collection “Blue” (Canio’s Editions, 1999), and “De Kooning’s Bicycle” (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2005), a brilliant novelistic prose celebration of the artists and writers who moved to the South Fork in the ’50s and ’60s. As John Ashbery said of the book, it’s essentially “the history of mid-twentieth-century American art.” Long, who was an art critic for The Star for many years, lived most of his life in Springs, and this book is certainly special, but it’s his poetry that will and should be remembered.

His poems cut back and forth from image to insight to insinuation like brushstrokes off a highly colorful palette making a provocative collage/parade of the casual and profane:

It’s like walking into a room

And suddenly realizing you’ve had sex with everyone there

At least once, watching your friends’ lives

Tangling as you all grow somewhat older,

Somehow more resolute. Bookshelves grow, too,

And you notice your handwriting becoming more matter-of-fact.

It’s as if all that comic smartness we glided through in youth

Were somehow desperate. And now we come to terms

With the sidewalk’s coruscating glamour,

The rows of dull but neat garbage cans,

Each with its own painted number,

The poodles and patrol cars, the moon rising high,

Like aspirin, over Eighth Avenue.

(From “Chelsea”)

Few poets are able to cram so much keen lyrical feeling and diverse imagery into such a small space with such an entertaining sense of urgency. His was a visual virtuosity born of an intense appreciation of his own odd-minded obsessions with, say, the art of de Kooning, Pollock, and Tiepolo, Formula One racing cars, and the visual splendors of the East End, not to forget Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen and Ninth Avenue, among others.

The language in his poems whirls, zigzags, and flows erratically, as if uncontrollable, though all by design. His prepossessing emotional dexterity was fashioned over a lifetime of looking at art. There’s something profoundly subliminal, spontaneous, and private in his work at the same time.

Although his being gay is present in the poems, it’s no more a subject than his politics, or his profound respect for his environment; it was what art turned, agitated, and reconstituted things into that mattered most to him, not ideas in and of themselves. His poetry is, essentially, as private and formally causal as he was, proffering an attitude of prepositional forlornness. Even the love poems are addressed to an unnamed anonymous “You,” coloring the intimacy with a second-person sense of privileged familiarity.

An ordinary car gliding past my house

And your regular breathing all those miles away,

In your room, on the other end of the phone,

Lying on your bed, speechless, receiver

To your ear, both of us not wanting

To hang up. And when we finally did,

You said “Seeya,”

Though you won’t, ever again.

(From “Little Black Dino”)

His is a world of drugs, booze, fast living, with a coating of nostalgia for Nowhereville, where angels write postcards and talk on the telephone. The lines whiz by on Librium, the images speak to one another in their own whispered jazzy two-tone language, a disjointed language of self-avowal and diligent watching, and endless surprise.

I’m comfortable here, on 50 mg. of Librium,

Two hundred bucks in my pocket

And a new job just a week away.

I can walk the streets in a calm haze,

My blood pressure down to where I’m almost human,

Make countless pay-phone calls from street corners:

Buzzing, they go by in near-neon trails,

People, people like me, headed for black bean soup,

For screams in alleyways, for the homey click

Of the front door’s closing, heading home

Past all those faces you know you’ve seen before . . .

(From “Chelsea”)

I’m playing the dilettante,

But it’s all out of my hands. One time,

I bought a velvet jacket from a speedfreak

on your corner. It was December. It was cold.

We had this great chat about the necessity

Of transacting business politely. We walked to the

Grocery so I could get change of a five, after

I’d tried on the jacket, out on the street.

People walked by. I had my gloves between my teeth.

“Whaddaya think,” I said. “Looks good,” he said.

(From “East Ninth Street”)

The wonderful lack of judgment, explanation, or apology throws the reader headlong into the excitement and desperation of the scene. Frank O’Hara, an early influence, did his own version of excited conversational truth-telling celebration, but Robert Long has taken that a step further. In the world of his poems the everyday lives side by side with off-kilter, hallowed feeling, a place where “St. Lucy is the patron saint of eyes” and we all get a “package from the Dessert-of-the-Month Club” whether we subscribe or not.

His finely honed, keen ability to see beyond where he’s looking probably accounts for his brooding sympathetic music and the high-mindedness of his anxious intelligence. He knew how to mix the high and the low, raw emotion with restraint, in order to register the deeper mysteries in the silence between words. De Kooning rode a bike but Robert preferred Enzo Ferrari’s Dino, a six-cylinder understated miracle that was “more beautiful than most painting, most poetry.” He deserves another look, as he speeds by. Who knows — maybe we’re all a little more ready for him now.

Philip Schultz’s books of poems include “Failure,” which won a Pulitzer Prize in 2008, and, most recently, “The God of Loneliness.” The founder of the Writers Studio in New York, he lives in East Hampton. A slightly different version of this essay appeared on the Library of America’s Reader’s Almanac blog.