The Role Model

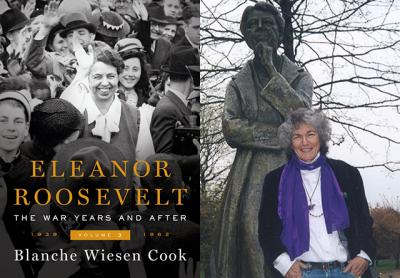

“Eleanor Roosevelt: The War Years and After”

Blanche Wiesen Cook

Viking, $40

Reading Blanche Wiesen Cook’s concluding volume of her three-part biography of Eleanor Roosevelt in the weeks following the 2016 election, one is struck by the parallels between her life and that of another former first lady much in the news this year, Hillary Clinton.

Both women excelled at their academic work and found early leadership opportunities in their school settings. For “ER,” as Ms. Cook calls Eleanor throughout her biography, the British boarding school Allenswood Academy allowed her to escape a painful childhood marked by loneliness and neglect, as she enjoyed great popularity among her fellow students and the doting attention of teachers who recognized her precocious intellect. For H.R.C., Wellesley of the 1960s provided the radical ground for her to leave behind the conventions of her rather conservative Midwestern upbringing for a more liberal path, a course Eleanor had always pursued.

Both women married young, setting aside a bit of their own personal ambitions for the political aspirations of their husbands, though this hardly represented a surprising sacrifice for Eleanor given the time period. As wives, Eleanor and Hillary endured the pain of their husbands’ infidelities yet refused to let those marital betrayals undo their husbands’ public lives even if doing so came at the expense of their own personal well-being. (Eleanor’s heartbreak over F.D.R.’s romantic liaisons forms a constant theme of the book, although she also pursued her own intimate relationships, including with other women.)

Far more liberal than their husbands, Eleanor and Hillary both tried to move them to the left while in the White House, with varying effect. F.D.R. often rejected Eleanor’s policy suggestions — and sometimes even refused to hear from her — but his presidency still showed the signs of her influence. “She was his conscience,” Ms. Cook writes, “and she knew it.”

After their time in the White House, both women expanded their political roles. Named by President Truman to the U.S. delegation to the United Nations, Eleanor helped author the monumental Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Hillary’s own political pursuits, of course, are well known, but it seems certain that she would not have been able to achieve — or perhaps even envision — so much of her political career and public influence had it not been for the history-making example of Eleanor Roosevelt.

Eleanor’s singularity — her unique and original life — stands out on each page of Ms. Cook’s thoughtful and thorough book. Ms. Cook, a distinguished historian and professor at the City University of New York, chronicled Eleanor’s life from her birth through the start of F.D.R.’s second term in two doorstopper-sized books published in the 1990s. Volume 3, which begins in 1939, lands just as heavily, coming in at nearly 600 pages, yet the constant delight of Ms. Cook’s book — and of the whole series — is how page-turning her account remains from start to finish.

Certainly, few 20th-century figures provide richer and more meaningful material to investigate than Eleanor Roosevelt. Yet the same work in the hands of a lesser biographer might easily have been weighed down by the sheer scope of Eleanor’s life and the relentless pace with which she led it. Instead, Ms. Cook balances her detailed examination of Eleanor’s political life, her active presence in the White House, and her tireless advocacy work, especially for civil rights and poverty causes, with a rich evocation of Eleanor’s complicated and often conflicted personal life, including the many friendships and associations that sustained her during her frequent bouts of depression.

What emerges is an engrossing and often moving portrayal of one of the most important figures of the 20th century who, as Ms. Cook argues, “changed history.”

Despite her privileged background, Eleanor “identified with, and worked especially for, people in want, in need, in trouble,” Ms. Cook explains. Eleanor’s difficult childhood as the daughter of an uninterested mother and an alcoholic father endured greater pain after both parents died two years apart when Eleanor was only 8 and 10. Orphaned and believing herself unloved, Eleanor channeled her personal hurts into advocacy for others, particularly the poor and African-Americans.

On matters of helping the impoverished, Eleanor and her husband generally found agreement, but the question of African-Americans and U.S. race relations opened up deeper divisions between the two. F.D.R.’s ability to pass important New Deal legislation, including the creation of Social Security, depended on gaining support from Southern Democratic legislators. The president ensured their votes by agreeing to deny Social Security benefits to domestic and agricultural workers, largely African-Americans, a political bargain that horrified Eleanor. She grew more enraged as F.D.R. failed to revise the Social Security Act to include African-Americans in the years after its 1935 passage.

But on other issues, Eleanor found her own way, working closely with the N.A.A.C.P. against lynching, pushing the military to end racial segregation, and providing critical support for Marian Anderson’s famous concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. In all things, Eleanor displayed her unceasing passion for the vulnerable, enflamed all the more by the seeming lack of interest of the powerful, including her husband. “No woman has ever so comforted the distressed — or distressed the comfortable,” her good friend Clare Luce Boothe once rightly said of her.

Spanning 23 years over all, the bulk of Volume 3 concerns the war years from 1939 to 1945. Eleanor, attuned as always to the sufferings of the powerless, vigilantly followed the plight of European Jews under the threat of Nazism. Over and over again, she pressed F.D.R. and the State Department to intervene on behalf of Jewish refugees seeking sanctuary in the United States, to little avail. Boatloads of Jewish exiles traveled up and down the East Coast waiting for clearance to dock as Eleanor tried to secure them entry, but most of them were denied, sent back to Europe to face a terrifying fate.

Eleanor’s frequent frustrations, both political and personal, with her husband structured her daily life. In private, Eleanor constantly pushed her viewpoints on the president, often provoking blistering wrath or chilling silence. (Her letters to friends and her diary entries recorded far darker thoughts, often undone as she was by the strained nature of their marriage.)

In public, Eleanor softened her criticisms, but she still occasionally used her “My Day” newspaper column — read by millions of Americans six days a week — to voice her disagreements with the administration. More often, however, Eleanor remained F.D.R.’s fiercest advocate, championing the provisions of the New Deal against a vicious assault from conservative legislators and throwing herself into the re-election efforts for his third and fourth administrations.

Initially she had not wanted him to run for a third term in office, but once she understood that the New Deal was at stake if he did not remain president, she rallied to the cause. F.D.R.’s fourth and final run for the presidency in 1944 was a foregone conclusion, coming as it did deep into the U.S.’s involvement in World War II. He won both elections in landslides, just as he had his first two.

F.D.R. would not live long into that last presidency, dying in April of 1945 at his personal retreat in Warm Springs, Ga., where he had gone to rest. Eleanor, who remained at the White House, received the news of his death by a phone call. She would later learn that their daughter, Anna, had arranged for Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd, F.D.R.’s mistress 30 years before, to visit with him in Warm Springs during his last days. That affair destroyed Eleanor when she had discovered it nearly 10 years into their marriage, but it had also helped set her life on a different path as she realized the relationship’s greatest potential existed in what the pair could achieve together politically. Ms. Cook notes that no historical evidence exists to tell us how Eleanor responded to this last betrayal by F.D.R.

For all the book’s detail, Ms. Cook ends her volume with a swift and thin accounting of the final 17 years of Eleanor’s life after F.D.R.’s death, a disappointing conclusion to an otherwise excellent and thorough series. Those years contained some of Eleanor’s most impressive accomplishments, not the least of which included her work as one of the authors of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a towering achievement that set the standard for human rights laws in nations around the world. Certainly Cook had to leave out or shorten elements of Eleanor’s life to keep the book a manageable size. But the decision to do this for the time after F.D.R. seems odd considering how much Eleanor accomplished on her own.

Indeed, if Eleanor Roosevelt is Hillary Clinton’s personal role model, as she has indicated, reading more about how much Eleanor still contributed to significant political change after suffering a terrible loss could serve as an inspiring example not only for the former first lady turned politician, but for all of us who have faced difficult setbacks.

Neil J. Young is the author of “We Gather Together: The Religious Right and the Problem of Interfaith Politics.” He lives in East Hampton.

Blanche Wiesen Cook has a house in Springs.