Saul Steinberg Centennial

It is difficult to believe that we observe the centennial of Saul Steinberg’s birth this year. Born at the very start of World War I, he is an artist who has transcended his era in quieter and yet more influential ways than many of his peers whose centenaries we have also recently marked.

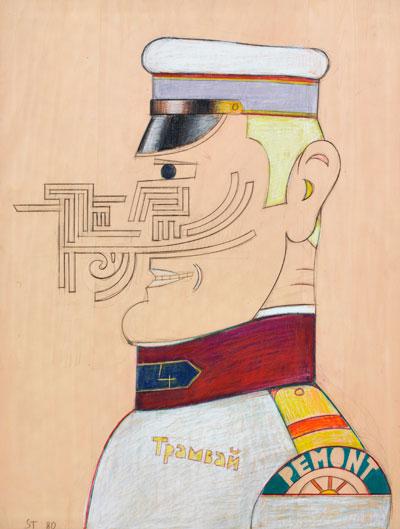

Steinberg’s singular takes on the absurd and the surreal, his interplay between mediums, and his sharp wit and use of language all anticipate the work of generations to come, particularly in a well-edited celebratory exhibition of his works on view at the Pace Gallery on East 57th Street in Manhattan.

Like many creative types of his era, Steinberg emigrated to the United States in the 1940s, a refugee from the fascism gripping Italy, where at the time he was a student. Editors of American publications that had already begun including his drawings in their pages interceded to help him enter the country.

Although married to Hedda Sterne, one of the New York School artists captured in the famous photograph of “The Irascibles” in Life magazine in 1951, his playful art, with inflections of Surrealism, was not of that strictly formalist and nonobjective world. Still, it derived from the same influences, and he was friends with many of them.

His postwar work included renderings of fanciful documents and certificates with elaborate cursive signifying absolutely nothing, the curved lines just that. The fake certificates appear to mock the papers required by the totalitarian governments that artists were fleeing. As he was skewering the self-importance and ridiculousness inherent in those items, he was also tackling modern art in post-modern terms.

The Pace show is on two floors. Upstairs, photographs from 1949, of painted drawings of women on or in bathtubs, are both witty and intellectually engaging, a cracked mirror reflecting back half a century of Modernist art movements and tendencies. Steinberg used the camera to reproduce his art in a way that made it part of it. His embrace of the photograph to portray a doodle was anathema to the artists who rejected as art the images it recreated so faithfully. His implied irony and the classical figure it employed, the bather, came not from the sensibilities of the era, but from the Dadaists he cut his teeth on while growing up in Bucharest.

This kind of irreverence and blurring of lines between mediums correlated more fully with the later neo-Dadaism of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg and the conceptual art of the decades to follow. It was not surprising to learn in the essay for the catalog that two of his favorite artists were Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol.

Steinberg took his work with the photograph to further absurdist ends: drawing figures on stairs, walls, the floor, and on the street, using props like boxes, paper, brooms, and bathmats to stand in for themselves or other objects. When he transforms footstools by drawing cartoon cat heads and tails on the walls and floor beside them, it is both amusing and transgressive, but not in any way cute. The faces look more like the masks of businessmen than animals, even the one drawn on the floor with the feet of the stool in the air as if ready for a belly rub.

It was in these years that Steinberg started applying things to photographs, including his own drawings, whiteout, and rubber stamps. To an image of a crumpled paper mountain, he applied an increasing number of stamped figures of his own design, titling each work, such as “Three Figures in a Landscape,” for the number of stamped images. It was another way of subverting a classic academy genre.

These relatively simple works were very complicated in their rejection of formalism and the privileged sanctity of the art object’s uniqueness (or, in the words of Walter Benjamin, its “aura”), in their serial nature as well as their co-option of the readymade and a foreshadowing of later installation art. For someone who spent his life in the one-liner world of mass-market print and cartoons, this was denser stuff, even when it was delivered via the photographic image of a challah bread on wheels.

Downstairs, the gallery exhibits a wider range of the artist’s work, including a series of drawings and sculptures inspired by his drawing tables, urban streetscapes, original artwork for published cartoons, and a westward-facing view from his apartment, similar to the one that became the iconic New Yorker cover and poster from 1976, still popular today.

In the catalog essay, Joel Smith notes that “a stint with the United States intelligence service in World War II turned him (after his own fashion) American, and got him comfortable in the role of a cultural spy.” Steinberg revels in the modern American city, yet finds something amiss and alienating about it and its consumer culture. The surreal nature of some midcentury architecture was also a recurrent subject, whether a skyscraper envisioned as a chest of drawers or‚ closer to his East Hampton home‚ the much-photographed Big Duck, set by the highway near Riverhead to advertise a local farm.

His generic landscapes, pretty backgrounds of green and blue horizons in oil on paper, became a series of backdrops for nothing as well as the most fanciful of inhabitants and buildings. It is worth noting that he was both an early avid reader and a student of architecture in his college years in Milan.

Steinberg lived well into his 80s. Like Duchamp, Rauschenberg, and Johns, who is, of course, still alive, his longevity surpassed many of his Abstract Expressionist contemporaries, who barely made it to their 60s. It is tempting to wonder if the quartet’s irreverence for the heroic art that most artists of their era held dear gave them longer and happier existences, particularly when the Steinberg show is such fun to behold.

The exhibition will remain on view through Oct. 18.