The Scroll That Defined the Town

The lawyer looked bewildered. He was representing one of the well-heeled residents of Georgica Pond, whose lawn was submerged because the traditional, Oct. 15 date on which the East Hampton Town Trustees opened the pond to the sea had not arrived.

The attorney had risen from his seat before the nine-member board to complain. “You don’t seem to realize that the pond is on my client’s lawn,” he told the trustees.

“And you don’t seem to realize that your client’s lawn is under our pond,” said Donald Eames, a trustee.

The response drew knowing sniggers from the board and members of the public attending the meeting. The lawyer stood speechless as though Mr. Eames had addressed him in a foreign tongue.

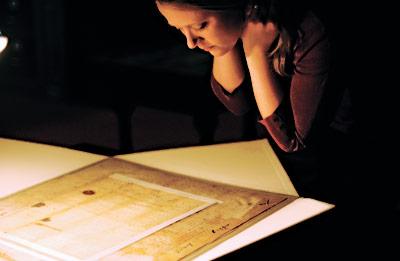

The back-and-forth took place in 1985 but it could have happened at most any time during the three and a quarter centuries East Hampton has been governed — entirely in the early years, and in part to this day — by the rules and rights guaranteed by three, two-foot-square pieces of velum that reside at the East Hampton Library.

The beautifully rendered cursive is faint now upon the darkened ivory pages, and a few tears have been repaired, but the importance given this document that predates the Declaration of Independence by 90 years can be seen in its construction.

Originally a scroll, two slits between the one-inch-high words, “Thomas” and “Dongan,” the governor’s signature, appear to be where the document’s seal closed the scroll. Ribbons probably passed through raised, rawhide crosses at each end of the scroll to bind it.

Friday marked the 325th anniversary of the day Thomas Dongan signed the document that to a large extent defines this place.

In December of 1686, Thomas Dongan was “Captain Generall, Governor-in-Chiefe and Vice-Admiral of the Province of New Yorke and dependencyes, under his Majesty James Ye Second.” Governor Dongan’s patent ratified an earlier writ issued to English settlers of East Hampton and other townships by Governor General Richard Nicholls.

The patent is in the form of a grant that assigned John Mulford, Justice of the Peace, Thomas Baker, Thomas Chatfield, Jeremiah Conklin, Stephen Hedges, Thomas Osborne, and Senior John Osborn as patentees empowered to purchase land from the “Natives Indyan Proprietors” and to create a governing body to be called the Trustees of the Freeholders and Commonalty of the Town of East Hampton.

Stuart Vorpahl, a former trustee and current town historian, said that settlers were not happy about the 200-pound-sterling tithe the governor was charging for the patent. “They had their Nicholls Patent,” he said.

But, given hostilities between the Dutch and English at the time, the mother country saw the wisdom of a stronger foothold, which would be made possible by giving settlers incentives to prosper. In fact, in 1673, just five years after Governor Dongan signed the patent, the Dutch retook New York for a short time.

“It finished crossing the Ts and dotting the Is,” Mr. Vorpahl said of the more liberal Dongan document. “Commonalty was defined as anyone below nobility. Trustees were a much stronger government, and it was subtle. The ‘appertances’ were the rights attached to the land, and one more thing,” he said. “In all my readings about Samuel Mulford, he always described the rights as ‘the law.’ The inhabitants of East Hampton considered the patent the law against the King of England. Except for gold and silver, he could touch nothing else. He saw the patent as the law against his majesty’s realm forever. He made no qualms about mentioning it. The legislature threw him out a couple of times, but he came out here and got elected again. East Hampton Town wanted a revolution a hundred years ahead of any other colonies.”

Mr. Vorpahl said that “Fishhooks” Mulford (when the Crown imposed taxes on whale oil, Mr. Mulford sailed to England to protest and sewed fish hooks in his pockets to snag pickpockets) knew what he was talking about. Luckily, he put a lot in print.

Descendants of the board’s first members, Thomas James, Capt. Josiah Hobart, Capt. Thomas Talmage, Lieut. John Wheeler, Ensign Samuel Mulford, John Mulford, Thomas Chatfield Sr., Jeremiah Conklin, Stephen Hand, Robert Dayton, Thomas Baker, and Thomas Osborne, continue to live here, as does the fundamental relationship between people and place that was set forth in Governor Dongan’s writ.

Dongan’s patent created the town’s borders and authorized the trustees to preserve the rights of East Hampton freeholders to use the town’s natural resources, “tracts and necks of lands, [. . .] gardens, orchards, fields, pastures, woods, trees, pasture, marshes, swamps, waters, lakes, brooks, streams, beaches, quarries, mines” and to maintain their right to “fish, hawk, hunt, and fowl.” The only exception was the crown’s claim to any silver or gold that was discovered.

So, when Donald Eames told the Georgica resident’s lawyer that his client’s lawn lay under “our” pond, he was voicing a long-held understanding that the natural resources found within the town’s borders were “common,” that is, public and that the public’s interest would always prevail “without the let or hindrance of any person or persons whatsoever.” Not to say the board is deaf to the concerns of property owners, and not there hasn’t been backsliding.

Just as commonage was carved up in England, public lands have dwindled here as well. The trustees have sold off land over the years, and agreed to give up Montauk in the 19th century when squabbles over land among descendants of Montauk’s original proprietors (overseers) could not be settled. They have tenaciously held on to most beaches and bottomlands, however.

“It’s hard to explain,” John Courtney, the trustee’s attorney, said of the patent’s enduring strength. “It was the foundation of the republic, in essence. It gave the inhabitants of the town the right to control their destiny through town meetings where people were elected. It’s where representative government came from.”

From a legal standpoint, Mr. Courtney said, the right to use beaches and bottomlands given to East Hampton freeholders by the patent were strengthened by the fact that the properties were literally owned by the trustees. “The patent gave rights along with fee title. It is not just title to real estate. It said to the colonists, you have what you need,” Mr. Courtney said.

Thus far, whenever its jurisdiction has been tested by either private interests or other governing bodies — as happens on what seems like an annual basis — the patent’s authority has been largely upheld in both state and federal supreme courts. Both state and federal constitutions acknowledge the legitimacy of Colonial patents.

Using the patent as a defense in recent times, the trustees have successfully defended their authority to control the construction of docks and shoreside structures, to manage shellfish populations, and to maintain vehicular access to beaches. In the past several months, two separate efforts to have the State Supreme Court rule in summary judgment against the trustees in suits brought regarding beach driving on Napeague have failed.

An effort by the state to create a saltwater fishing license went down in flames earlier this year in large part because of Dongan Patent-based opposition to it from East Hampton and other townships with similar beginnings.

Messrs. Mulford, Baker, Chatfield, Conklin, Hedges, Osborne, and company could not have imagined Facebook, but so ingrained is the patent’s potency in East Hampton’s collective mind that last summer residents turned to the social network to launch the Committee for Access Rights. The group supported the trustees’ defense of public access in the two suits brought by beachfront homeowners on Napeague, while at the same time demanding that the town government remember its roots.