In Search of the New

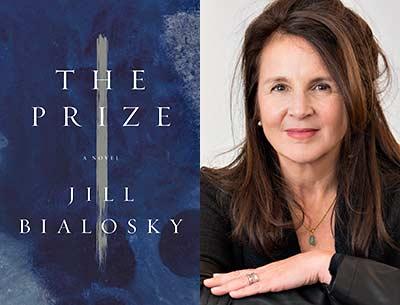

“The Prize”

Jill Bialosky

Counterpoint, $25

Many notable books have been written about the dramatic intersection of art and life, exploring how each informs the other and speculating on their relative value. They’re often fictional takes on actual artists, from the old masters to more modern figures. In “The Prize,” Jill Bialosky’s absorbing new novel, the focus is on an invented protagonist, Edward Darby, a dealer in contemporary art, a middleman devoted to the work he represents. Although the New York City gallery he runs, but doesn’t own, must turn a profit to survive, Edward’s commitment is more idealistic than materialistic. As he sees it, “Art, in essence, was priceless.”

His boss, May, an elderly woman with a “face powerful as a building,” displays genuine esteem and affection for him, but her concerns are practical. “If you love art then you’d better get out of the business,” she tells him, playfully and seriously at once. Still, inspired by his late father, Harold, a scholar of Romantic poetry, Edward believes in the holiness of art, that it offers “a refuge from the trouble in the world.” For the sake of the work itself, he patiently courts his artists and nurtures them — as confidant, critic, therapist, and agent.

Edward’s career and his sense of serving the larger cultural good come to depend largely on the well-being and success of a particularly gifted and neurotically needy young painter named Agnes Murray, whom Edward positions, to her delight, “as a new Old Master.” Agnes is married to Nate Fisher, another artist — once her mentor but now her fiercest competitor, and possibly even her saboteur. Both of them use images of 9/11, the most significant event of their time, in their paintings.

Edward counsels and comforts Agnes about her art and her life, even keeping her company on one occasion until she falls asleep, like a protective parent with an anxious child. She frequently expresses her reliance on his judgment, and her enormous gratitude. Thrilled by their close collaboration in mounting a show, she gushes, “You have the ability to bring to life what’s in my head.”

But when he offers some fairly gentle but honest criticism of her newest paintings for an exhibit that could make or break May’s gallery and her own reputation, she responds petulantly, while unpinning and shaking out “her hysteria of hair.” Agnes feels threatened rather than grateful for Edward’s guidance this time around, and she threatens defection in return.

Edward’s personal life is in dire jeopardy, too, as he and his wife, Holly, a volunteer at an animal refuge, drift away from each other, emotionally and physically, and he becomes more and more obsessed with Julia Rosenthal, a married sculptor. As with his passion for art, he seems at first to take the high road. When he and Julia are sitting in a bar, he thinks, innocently enough, “It was a luxury to be quiet with another person,” even though he’d ruminated earlier about her neck and eyes and skin, concluding that “It was a vacation just to look at her.” But as they keep meeting, accidentally, in the beginning, and then deliberately, at art conferences abroad, his sexual desire is more blatantly realized and expressed

Returning home to his wife and beloved teenage daughter from a trip to Berlin, where he and Julia have teetered on the edge of an affair, Edward doesn’t feel the usual anticipatory joy of reunion but won’t really take responsibility for his change of heart and mood. The house is dark. Holly isn’t there to greet him with a welcoming kiss and a hot meal. And while admitting to himself he’d momentarily forgotten that her father is gravely ill, he vaguely places blame elsewhere, even finding that “The key no longer turned with ease, he had to jiggle it. . . .”

There are two parallel lines of suspense in “The Prize” — whether Edward will succumb to his attraction to Julia and further endanger his marriage, and whether the volatile and narcissistic Agnes will enhance or ruin him professionally.

As the novel progresses, more and more of Edward’s inner life and its conflicts are gradually revealed. We learn of a brief earlier marriage to a fellow college student named Tess, and of her tragic death during an estrangement — essential biographical facts he’s somehow never shared with Holly. When he tells Julia about Tess, this seems like an even larger betrayal of Holly than his extramarital longings.

We also learn that Edward impetuously purchases very expensive accessories — gloves and scarves he can’t afford and that he hoards but never wears. He defends this odd practice by viewing those articles as objects of beauty, like the art he worships, and rationalizing that using them would make them “ordinary, like everything else.” And perhaps he ascribes to the German Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin’s idea that “ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects.”

Edward also wonders if betrayal is another form of intimacy. But as he finds it harder to justify some of his other thoughts and actions, he seeks guidance (and perhaps absolution) from a psychotherapist. Yet even in the safe professional setting of her office, he withholds certain information about himself that would expose him to uncomfortable scrutiny. And he continues to act in ways that echo the self-destructive tendencies of his revered father. Although we are always in Edward’s point of view in the novel, we can discern and understand (much sooner than he does) Holly’s disappointment and rage when some of his secrets are finally confessed. The reader is compelled to question whether this tattered marriage can possibly be saved.

Edward has suffered two great losses, of Tess in an accident and of his promising young father to an overdose of lithium. Sometimes he appears to navigate his days in a kind of fugue state in which the past that so influences the present for him is of more consequence than his tenuous future. He keeps shouldering the burden of guilty grief over Tess, while his father’s brilliance, along with the consequences of his mental illness, resonates in Edward’s mind. “He didn’t know what was worse, to be ordinary like his mother, or to strive for the perfection that had taken his father away from her.”

Like Edward, his father, too, was a man of secrets that his son feels compelled to uncover, a painful process that brings some comfort and a resolution to the mystery of Harold’s unfulfilled promise.

The eponymous “Prize” doesn’t come into play until nearly the end of the novel, when Agnes Murray, whose loyalty to Edward and the gallery is still in flux, is in the running for an award that can cement the critical and commercial success of the winning artist. Agnes’s hot and cold relationship to Nate, as well as her own (and Edward’s) professional fate, is also a factor in the contest. Adding to the tension, another gallerist, far less principled than Edward — “He’d befriend a serial killer if he thought it would get him somewhere” — vies with him for both Agnes’s and May’s favor. And all the while, Edward fears that “he’d not only lost his edge, but perhaps worse, the ability to be truly moved.”

I love reading novels that enlighten me about a given subject without seeming didactic — glove-making in Philip Roth’s “American Pastoral,” boating and fishing in John Casey’s “Spartina.” “The Prize” depicts the machinations of the art world — from aspects of craft to those of commerce — in fascinating detail. As the adage says, life is short and art is long, but not all of the latter has permanence, as Edward discovers in his constant search for the newest definitive work.

Jill Bialosky wears several literary hats; she is a respected and admired editor, poet, and memoirist, as well as a novelist, and the many strengths of “The Prize” reflect that varied experience. It’s a shapely, well-researched book, written with a poet’s clarity of language and a memoirist’s psychological insight. Best of all, it is a work of novelistic imagination with a fine sense of felt life.

Hilma Wolitzer’s novels include “An Available Man,” “The Doctor’s Daughter,” and “Hearts.” She lived part time in Springs for many years.

Jill Bialosky lives in Manhattan and Bridgehampton. She will read from “The Prize” at Canio’s Books in Sag Harbor on Sept. 19 at 5 p.m.