In Search of the Underground

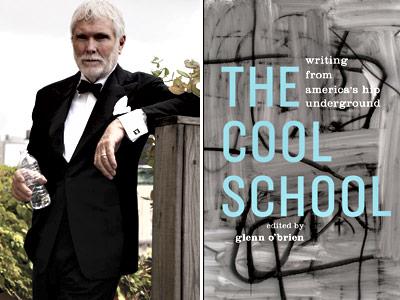

“The Cool School”

Edited by Glenn O’Brien

Library of America, $27.95

It’s early in 2014, but I’m already throwing in my bid for most rankling title of the year with “The Cool School: Writing From America’s Hip Underground.” It takes a special kind of hubris to declare oneself an arbiter of cool and hip, never mind the naiveté to ignore the effects of years of irony on these words, mangled as they are now to the point of near incomprehension.

“Hip,” as most of us know, has more likely become the idiom of advertising rather than modern parlance, and, arguably, is just as often used as a term of derogation and satire than as a compliment: “Tragically hip” being one example, along with the Brooklyn “hipsters” who work in finance or for dot-coms during the day and don fedoras by night, as if bohemianism were just six ounces of apparel away.

What a relief it is then to open this volume, edited by Glenn O’Brien, a Rolling Stone writer, and see that the editor is hip to the irony, as evidenced by his superlative introduction. “The scary thing about this project is that you begin to realize that the underground as we used to know it doesn’t exist anymore except in our nostalgia for it,” writes Mr. O’Brien. “Marketing has simply turned the forbidden, the underground, the enemy even, into something marketable.” No one is hip when everyone is; it’s just another demographic.

So what was hip, back in the day? There has never really been a satisfying answer to this. Generally it is agreed that hip came out of the lingo and lifestyles of the black jazz musicians of the late 1940s, spilling over from the clubs into white culture. This begot the Beats, the white embodiment of hip: creative, anti-corporate, impulsive, promiscuous, sometimes gay, often high; the living antidote to the staid ’50s.

Included in “The Cool School” is an excerpt from Norman Mailer’s difficult but quintessential 1957 essay on hip titled “The White Negro.” Mr. O’Brien summarizes it aptly: “Mailer’s hipster is a white man who removes himself from the culture because of existential dread. Dread from the A-bomb’s threat of mass extinction or the corporate world’s mass identity extinction.” Mailer’s essay is even more specific: “One is Hip or one is Square . . . one is a rebel or one conforms, one is a frontiersman in the Wild West of American night life, or else a Square cell, doomed willy-nilly to conform if one is to succeed.”

How quaint this all seems — at least from a contemporary perspective, where the consumer culture flatters us that we are all cool, or just a car lease away from unleashing the rebel inside us. So indeed “The Cool School” is a nostalgia tour, with most of the selections here 50 years old or more. There are omissions — Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” being the most glaring — but the writing featured here is mostly very good and tastefully chosen. There’s a heavy emphasis on the legacy of jazz, of course, with excerpts from the autobiographies of Miles Davis and Art Pepper, the latter especially searing in his self-laceration, as well as an interview with Lester Young.

The Beats, of course, get their turn, with a particularly paranoid selection from William S. Burroughs’s “Nova Express”; a letter from Neal Cassady to Jack Kerouac (“I’m sitting in a bar on Market Street. I’m drunk, well, not quite, but soon I will be”), and Joyce Johnson’s forlorn memory of Kerouac in “Minor Characters.” There is the funny and sad poem “Marriage” by Gregory Corso (“Should I get married? / Should I be good?”), and Kerouac himself in an article for Playboy, trying to explain exactly what Beat “means,” and growing pugnacious in the process: “But yet, but yet, woe, woe unto those who think that the Beat Generation means crime, delinquency, immorality, amorality . . . woe unto those who are the standard bearers of death, woe unto those who believe in conflict and horror and death and fill our books and screens and living rooms with that crap. . . .” Too late for that, Jack.

The writers with ties to the East End fair less well. A sweet but minor poem from Frank O’Hara, “The Day Lady Died,” announces he will “go get a shoeshine / because I will get off the 4:19 from East Hampton / at 7:15 and then go straight to dinner / and I don’t know the people who will feed me.” There’s a section from Andy Warhol’s forgettable “a: a novel,” and the pages from David G. Rattray’s “How I Became One of the Invisible” hits that “On the Road” vibe it strives for, but fails to offer anything fresh or distinguished.

By the chronological end of “The Cool School,” the quality of the selections grows more inconsistent. The anger in the poems of Emily XYZ may bear some relation to hip, but that doesn’t necessarily make them any good, and Eric Bogosian’s excerpt from “Pounding Nails in the Floor With My Forehead” works better as a performance (which was its origin) than as a piece of prose.

Perhaps it isn’t surprising that by 1990 Mr. O’Brien strains to find writing that fits his collection. The very idea of a “hip underground” implies rebellion, but how to rebel when everything is permissible? In Kerouac’s Playboy essay he argues, “. . . America must, will, is, changing now, and for the better I say.” That was 1959. We now live in an age of gay marriage, legalization of marijuana, and a black president. The culture war is over: The hipsters won. Whether we’re better off is debatable.

What’s not debatable is that it was the artists who were on the front lines of that war, and many of the most prominent are well featured in “The Cool School.” It’s a legacy worth remembering.

Kurt Wenzel’s novels include his 2001 debut, “Lit Life,” and, more recently, “Exposure.” He lives in Springs.