Secrets and Lies

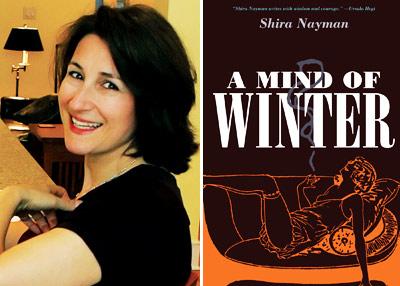

“A Mind of Winter”

Shira Nayman

Akashic Books, $15.95

“I do not fail to see the irony in it — being taken, once again, for someone else.” So begins “A Mind of Winter,” the second novel by Shira Nayman. It commences like one of those P.O.V. video games where one sees out of and controls the movements of the viewfinder (all too often in video games, over the barrel of a gun) but one cannot see oneself. We, the readers, do not know if the first-person narrator is male, female, young, or old. The narrator is nameless. We see out of his or her eyes without knowing who is steering our perspective. Clearly this is intentional, as the book is, foremost, about identity: mistaken, taken, lost, sought after, invented, constructed, and found.

The novel takes place, mostly, in the decade following World War II. It is (somewhat confusingly) discontinuous in chronology, geography, and narration. The locale jumps from the North Shore of Long Island to Shanghai to London to Germany and back, while at the same time switching from the 1950s to the late ’40s to the war years and back. Each of the first-person narrators (there are three: “Oscar,” Christine, and Marilyn) tells a part of the story, but because the narrators are inventing new or improved personas out of their pasts, and each has reasons for dissembling, hiding, and manipulating both the past and the present, the storyline becomes blurred and confused. Add to this the fact that Christine, during much of her narration, is falling into the tunnel of opium addiction, so her view of events begins to feel slippery, obscure, addled, and dark.

Oscar tells us in his prologue (summer 1951, Long Island): “We could not be more different from one another — Christine, Marilyn, and I. And yet, I see us as three comparable figures, up against the same squall. Only this too: I may be battling alongside them, but I am also the eye of the storm, the terrible, still center. Not merely one of the hurricane’s combatants, but somehow also its source, and therefore, as it happens, a void, which is to say, nothing at all.”

Oscar also informs us: “I stand accused of murder. A crime of war. A crime, to be precise, against Humanity.” We do not know if he is guilty of the crime, we do not know what the crime is. We don’t know if there are extenuating circumstances. We don’t even know if he actually did the thing he is accused of. And it is not until the very last pages of the book that we get even an inkling of just what it is he might be accused of. But the accusation hangs over the novel like a sword of Damocles. Is Oscar, who started as Robert and becomes a Harcourt, a Nazi? Whom did he murder? During the war? After?

The next section takes place four years earlier in Shanghai. It is mostly concerned with the British-American expatriate community. Christine narrates. She smokes opium with Barnaby, her lover. His use of the drug is clearly casual and recreational. Her need for the pipe is a physical discomfort. She is twitchy and greedy for it. Eventually, the opium that he brings to share with her is not sufficient for her deeper needs, and she must go to Han Shu’s cafe, one of Shanghai’s opium dens, to actually buy it.

Christine is a beautiful Englishwoman. But she is down on her luck and running out of money. Her landlord wants the rent, and her clothes are getting shabby and dirty. She smokes more and more opium and one begins to fear that she will have to become a prostitute to support her habit. Instead, at least for a while, she makes an accommodation with Han Shu and becomes a kind of madam/English teacher to his harem of barely pubescent Chinese prostitutes. In return for teaching them spoken English, literature, and manners, she gets room, board, and enough opium to lose herself in a hallucinogenic haze every evening. She eventually takes Han Shu as a lover. The irony here is that Christine’s mother was a kind of casual prostitute, taking in different men all the time.

The gentlemen were always gone by the time I awoke, and my mother would be transformed — hair in pins and rags, bustling about the small kitchen, tending to eggs sizzling in lard, the loose housedress only emphasizing her lovely shape. . . .

And when the men started coming into my tiny, private space — occasions when the gentlemen lavished on my mother too many glasses of the amber stuff, so that she would end up draped across the green brocade couch. . . .

But what Christine tells Robert of her childhood is none of this. She creates a false self, a lovely and gentle story about an innocent little girl in a white cotton dress. We don’t know at this point that Robert is also a false self.

In the next section of the novel, we are returned to Long Island in 1951, but now the narrator is Marilyn, who, we are told by other characters, physically resembles Christine. Marilyn is a wartime photographer putting together a book of the wartime photos of others. She is married to Simon but living at Oscar’s North Shore mansion and having an affair with Barnaby. Of necessity, Marilyn too has a false self: the one that she presents to her husband, and even the one that she shows Barnaby. He tells her ironically, “As for the truth quotient: that’s not for me to judge. Besides, isn’t that the business you’re in? The photographer, going about the world with a camera — teasing the truth out of things?”

While Marilyn and Barnaby are sneaking about the mansion and its grounds, meeting for secret trysts even while her husband is present, there is someone else sneaking around too. At first Marilyn wonders if it is Simon, trying to spy on her. But eventually she learns that it is someone from the Department of Justice, the Office of Special Investigations. These agents investigate war crimes. He is meeting secretly with Oscar, and sometimes they speak in German. The mystery mounts.

The writing in “A Mind of Winter” is sometimes quite poetic and lovely. When Oscar is taken in by an English family whose son, whom he resembles, died in the war, he says, “You might think that my precipitous success in the [family] company was spurred by a desire to repay my hosts and mentors for their extreme generosity and faith. I wish I could claim this as a motive. The truth is, I was driven by what felt like a demon: ugly and vengeful, greedy and frothing with lust. A demon with appetites I did not understand or care to understand.”

“A Mind of Winter” is a novel filled with false selves, falsehoods, and layers of lies and deceits. At one point Oscar muses, “Does the erasure of deceit result in the revelation of truth?” I suspect that is Ms. Nayman’s very own question, and one that she handled . . . deceptively herself. As the author, she withholds much information until the very end of the book. We are left very much in the dark about essential elements of the story, especially the particulars of Oscar’s history. It seems information that is coy to withhold.

Shira Nayman is a clinical psychologist who has taught literature at Columbia and psychology at Rutgers. She lives in Brooklyn.

Michael Z. Jody, a psychoanalyst and couples counselor in New York City and Amagansett, regularly contributes book reviews to The Star.