Seeing ‘The Big Picture’ at MoMA

It has become trite to say that an art exhibit is revelatory, but when a show like the Museum of Modern Art’s “Abstract-Expressionist New York: The Big Picture” comes along and manages to debunk the very history and assumptions that the museum has encouraged since the first stirrings of the Modernist impulse, it is difficult to find other words to describe it.

Drawn entirely from the museum’s collection, with many of the works not likely to have seen the light of day in decades, the exhibit reminds us of the exclusive role the museum had in forming what would become the accepted Modernist cannon.

Any student of early-20th-century art will immediately recall the chart Alfred H. Barr Jr., MoMA’s first director, devised to explain the derivation of the major movements of that period. This exhibit shows how that same influence moved into the midcentury. It presents the almost exclusively New York artistic phenomenon that could really only be navigated and understood by a New York institution.

According to the exhibit’s catalog, the last time the museum mounted a similar comprehensive show of these artists was in 1969 by William Rubin, the museum’s curator through the last part of the 20th century. Ann Temkin, the curator of this exhibit, noted that generations of museum visitors and even museum staff have not had a similar opportunity to examine this period of the museum’s collection in depth.

The “superstars” of the collection have always been on view, whether in the old museum or in its remodeled and expanded galleries. Rather than gallery upon gallery of “high” Abstract Expressionism, the show presents several artists’ journey there, with their work sometimes mixed in with the rest and other times given a monographic treatment in solo galleries.

Surprises occur just in the breadth of examples of some artists’ work and the dearth, or at least lack of good examples, of others’ work. That represents a lost opportunity for the museum, which could have collected so many more works at the time of their creation had it wanted to do so.

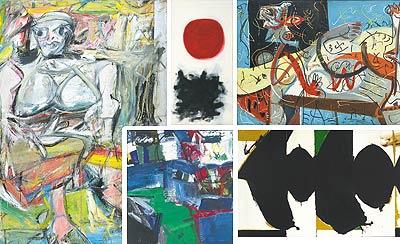

The Willem de Kooning painting “Woman I” is here, of course, because of its iconic stature, but it is only one of four paintings included by the artist. A black- and-white “Painting” from 1947 is also included. Both of these paintings were purchases by the museum and show an early commitment to the artist.

Jackson Pollock’s “One: Number 31” is another work never likely to go off view and was also a museum purchase. But the exhibit also shows 12 other works by Pollock, including a painting called “The Flame” from the mid-1930s and a number of Surrealist-inspired abstract works in addition to the iconic drip paintings and those quirky ones that came after.

Mark Rothko has received similar career-spanning treatment by the museum. He is so well collected by the Modern that in a series of rooms and walls devoted to him, a viewer can trace his Surrealist beginnings through his first patchy departures, to the solidification of those patches into the striated mass of colors that would define his mature style, up to one of the last paintings he completed before he died.

More surprising is the treatment of Adolph Gottlieb, who spent the last decade or so of his life in East Hampton, and whose mysterious blasts and pictograms have always defied a neat inclusion among this group. Gottlieb is represented by six works, a respectable number, and the paintings are shown in small groupings in different rooms, demonstrating their easy assimilation within the other tendencies in painting happening at the time.

Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, Ad Reinhardt, Arshile Gorky, Philip Guston, and David Smith are also granted a range of examples in this show.

With a public used to the “greatest hits” kind of presentation that most museums can afford these days in terms of space, it bears acknowledgement that the assumptions these “drive-by” examinations foster and preserve need to be shaken up once in a while.

By its inclusionary nature alone, this show manages to engage in some welcome revisionism. Larry Rivers’s “Washington Crossing the Delaware” might have been unthinkable in such company even a decade ago. His proto-Pop realism was never embraced by the formalists championing the abstract artists of this era, even though Frank O’Hara, a curator of the museum, was a friend and supporter. That the painting was acquired thanks to an “anonymous gift” around the time of its painting seems to be a kind of rebuke to the museum.

The quality of the museum’s Franz Kline paintings also points to a similar oversight or even slight of the artist during his lifetime. The paintings are certainly not his strongest works. Had the museum made him a priority, there are far better examples it could have collected. Instead, the assemblage of gifts and bequests are weakened by the circumstance and take away from the artist’s actual achievement.

Hans Hofmann’s three works early on in the show are a nod to the artist’s overarching influence on this group, stemming from his education of many of them, but again show a surprisingly lax approach by the museum to acquiring his work.

The inclusion of women in any significant way is always news in this group known for macho attitudes and behavior. Lee Krasner is represented by three very strong paintings, but all of the women in show have important pieces there. Hedda Sterne, Grace Hartigan, Louise Nevelson, and Joan Mitchell look right at home and should because in the early days their work was included in many cooperative gallery shows with the same male artists. The women’s work is particularly powerful because it had to be exceptional in order to attract the same attention as the men’s.

Many male artists of the period whose recognition at the time was lost to history are back on the wall. It is great to see a painting by East Hampton’s James Brooks included here, and there are still more by artists, some of whom I had not heard of, who were doing great work at the time. Photographers are also included and given a context for their point of view during this time.

In a separate exhibit of art and documents that ran concurrently with “The Big Picture,” the museum examined the role of the Eighth Street club of artists led by Philip Pavia, known informally as “The Club,” whose weekly discussions and panels solidified the ideas that underpinned the movement. That show, along with an exhibit of works on paper from the era, closed in February. “The Big Picture” is on view through April 25.