Sheets to the Wind: The Blues

“You’re Holly Golightly on the outside, and Kafka on the inside,” Frederic said over the phone.

“I’m a cockroach!” I hiccupped, tears streaming.

It was Wednesday. I was sitting on a bench on Main Street, having come into town to use the phone. I have no cell reception at home and, also, living in Manhattan for 20 years has made it so I can only feel truly alone when surrounded by people and with a siren whirling in the distance intimating the suffering of a stranger I’m free to ignore. I had just told Frederic I was depressed. “And anxious. I’m not cut out for journalism or for party reporting. I have this recurring nightmare where I’m at a party, and wake up screaming, ‘It’s good to see you, too!’ ”

At noon on Saturday, I was lying on the sofa with the blinds drawn watching Showtime’s “The Affair,” which makes adultery seem as appealing as dysentery. What’s the upshot? I wondered, watching the characters frown and get cancer in one of the show’s lighter sequences. I looked at the clock.

When you have the blues it colors everything, like an Instagram filter. You feel sad first, and then try to give it cause. The same circumstances on a different day might cause you no distress, but on a blue day, you mope and say, “Time to get ready for the Tea Dance,” as if putting on a party dress were stepping into an iron maiden. In my defense, my tasteful and flattering ankle-length floral dress pinched.

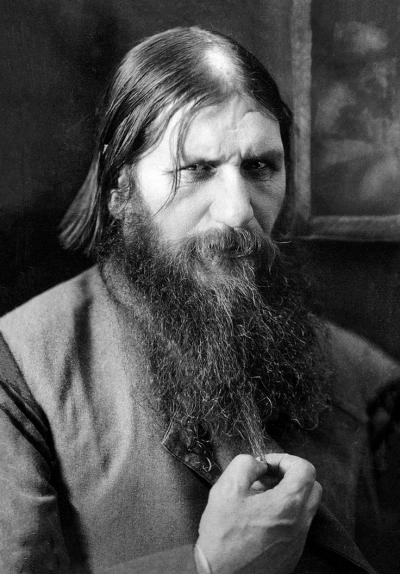

The spikes stabbed relentlessly as I drove to Nova’s Ark Project in Bridgehampton, where the 26th annual Hamptons Tea Dance, benefiting the LGBT Community Center, SAGE (Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders), and Callen-Lorde, was being held. I thought about Rasputin in an effort to cheer myself up. “Try to think about someone besides yourself for a change,” I read once on a self-help website and took the advice to heart.

I parked in the outer field and hobbled over the grass toward a cluster of white tents, toward cheerful horses galloping in the distance, toward a sea of colorful shorts, toward great metal sculptures, toward music, toward sky. The breeze carried the disco, while the disco carried the D.J. drag queen Lady Bunny out from behind her turntables.

She bounded, goddess-like, down the small stage as I approached the main tent. Stopping mid dance floor, Lady Bunny began to twirl, her magnificent iridescent dress catching the light and giving it back better, her hair, blond and bullied, reaching skyward in a defiant bouffant, her arms going up and up. And was I ever sad? Was there ever a time before there was Abba? Was that a Dreesen’s doughnut truck off to the side? Was that a crowd gathering round to dance with Lady Bunny? Was that longtime SAGE donors Dr. William Kapfer and his husband, the Starbucks lawyer Eric Baker, saying hello? Was that me dancing, too?

Brian Mott, John Omlor, Steve Gorman, and Jimmy Mack, who escorted the late Edie Windsor last year, sipped drinks in the field. April Hoo and her Genoa-born friend Gioia Grabos, who founded the same-sex wedding planning company Same Love, Better Wedding, relaxed on the giant rainbow flag set down as a picnic blanket. Nearby, Zach Howell and Garrett Hall lolled with their twins Clark and E.J. I chatted up the three drag queens of Stephanie’s Child after their performance. Jansport — named after the sturdy backpack — Laguna Bloo, and Rosé. Laguna, also in heels, complimented me on mine — “The block heel was smart. Mine [stilettoes] are sinking into the grass.”

I didn’t want to come and now I didn’t want to go, which is like life I suppose, but I had promised to meet my friend Marianna at the Hamptons Greek Festival, which is also like life on those days when you do just that.

In traditional Greek costume, the children’s dance troupe was making its circles before the bouzouki band when I arrived at 7 p.m., as a smiling Father Constantine, pulling wads of dollar bills from his black robes, made it rain over and the crowd of surrounding families cheered.

Marianna and I applauded, then hit the souvlaki tent, waiting on line next to three rotating spits of lamb whose hooves were raised around their faces like Munch’s “The Scream.”

We were finishing our dinner when I heard the first strings of the Syrtaki and pulled Marianna onto the dance floor, empty. Marianna worried she didn’t know the steps but picked it up immediately, and soon we were joined by others, whirling in a mad, ever-growing circle as the music accelerated and we laughed trying to keep up with it.

Catching my breath, I spotted the eminent ophthalmologist Dr. Peter Michalos mingling among the far tables. Night fell and the carnival lights came up. “I love this time,” Marianna said, after confessing she, too, had been feeling blue earlier. “I didn’t want to come, but am so glad I did.”

We browsed the shopping stalls, a table set up with saints painted onto sparkly granite, where Marianna picked up a St. Mary and said she missed her German mother who used to take her to the Greek festival every year. I chatted in my broken Greek with the store’s proprietress, Irene, who it turned out is from the same part of Athens as my own family. She gave me a gold St. Savas to take home.

I bought Marianna an evil eye pendant that she wanted to buy for herself. “For protection,” I said. “It works better if someone gives it to you.”

“Is that true?”

“Seems like it should be,” I said happily, though Rasputin couldn’t have been further from my mind, as we walked toward a stall of stuffed animals I hoped to win.

Marianna and I threw balls into a bucket, but not enough to take home the tiger I had my eye on. John, who’d taken our money, gave us tiny stuffed bowling pins in consolation and winked.

We tried to find a ride that wouldn’t make us queasy, but most were of the spin-you-around variety, so instead of getting on, we sat beside a turn-y thing and watched the little kids fly through the air. Marianna, whose husband was at home and whose teenage daughter was at the Surf Lodge fibbing about her age, reminisced about her first date, which was at a carnival. “These spinny ones are the best, because they push you up against each other.”

And it was dark now, and the smell of honey over freshly baked loukoumades filled the air, and we strolled arm in arm as we looked at the teenage boys running the rides and imagined how we might have crushed on them when we were girls. “That one looks very bad,” I said, as he strapped a few kids in. “I bet he doesn’t care about anything,” I said. “I bet his kisses are sloppy and addictive,” I said, and Marianna warned me against him as if we were both 15 and I were daring and wild.

We bought sodas and ran into Maryann Calendrille and Kathryn Szoka of Canio’s Books in Sag Harbor, and chatted with Father Constantine, who’s writing a memoir about his dad called “The Rise and Fall of the Gus Lazarakis Company,” before he was pulled away by Helice Carris, a parishioner who was visiting from Chicago, and we walked with the painter Walter Us and Faith Diskin, and said hello to Paul Strassfield whose Greek wife, Christina, runs the gallery at Guild Hall — “She’s the earth and I’m her moon,” he said — and then I heard my name coming from a dark table where sat

Helen Matsos, who produces “Star Talk With Neil DeGrasse Tyson,” and her boyfriend, a former soccer player, Gary O’Reilly.

Marianna, who used to live in England, is a great soccer fan and was excited to meet Gary. She quizzed him about the other players of the Tottenham Hotspurs, while Helen and I danced in our seats and talked about a potential venue for the next Sci Hamptons, the science festival she’s started.

“My place? I have this natural history museum in my house.”

“That’s a great pickup line. Even better than come see my etchings. Can I steal it?”

“It’s full of fossils and taxidermy. I inherited it from my ex-husband. He’s a scientist and was trying to popularize a new theory of evolution, which is sort of why we broke up.”

“As good a reason as any.”

I told her why I broke up with my ex: “We were having dinner and I asked, ‘If you were convicted of a crime in a Kafkaesque court and the judge sentenced you to either have sex with an animal of your choosing or be put to death what would you choose?’ He wouldn’t answer, so I said, ‘You mean you’d rather die?’ and he said, ‘No, I’m not going to answer that,’ and I said, ‘Why not,’ and he said, ‘Drop it,’ and I began to cry, and while we didn’t break up right then, in retrospect I realize all our arguments could be boiled down to that one. Why wouldn’t he answer?” I asked in a fit of blue.

“Horse,” Helen said, supportively. “I’d go the Catherine the Great route.”

My feet were killing me in the best way: They were tired more than homicidal and wanted only to dance more, so I said goodbye to Marianna and zipped off to the Parrish Midsummer Party, the theme of which was neon and white in honor of the artist Keith Sonnier.

I changed my clothes in the car, putting on a fluorescent orange sequin skirt and a T-shirt I made for my sad days, which says, “I Love Cliff Clavin.” I made it expressly to wear while watching TV. It’s blue to match the blues, and also the-know-it-all postman’s uniform on “Cheers,” my favorite show.

I met Sarah Maslin Nir, the Pulitzer Prize finalist for investigative reporting and gold lamé enthusiast, out front, and together we wandered the halls, looking at art and women painted in their own fashion and a few men, their collectors. Ball gowns mixed with party dresses — one woman wore a white mini covered in a clear plastic tube.

Sarah just left The New York Times on “book leave” to write her first book, “Horse Crazy,” which will be about her love of horses, she told me. I tried to smile the right amount, neither too much nor too little, as it was our first friend date, and I was nervous. I’ve known Sarah for five years, but she never remembered meeting me during most of the first one. From the beginning I admired her quick wit, her lamé, her confidence, her success. Younger than me, she’s part of this group of young media women who were all successful out of the gate, who got serious jobs right out of college and worked their way up to writing and editorial positions at major magazines and newspapers. When I met them, I had just published my first novel, which they seemed to find impressive enough, but it was about being a screw-up and was, in that respect, about me.

“How’s the reporting?” Sarah asked, having come as my press plus one.

“I just go to parties. I’m not much of a reporter,” I said, feeling sheepish beside a real one. Sarah also wrote for The East Hampton Star — when she was 16.

“Sure you are! I used to write The Nocturnalist column at the New York Times and I always thought of it as real. I went to 268 parties in 12 months,” she said, though I didn’t write this down, so I may be getting it wrong. Instead of taking notes, I counted on my fingers the handful of parties I’ve attended this summer, which already felt like too many. I thought back to my conversation with Frederic earlier in the week: “I can’t keep this up! I’m terrified of talking to people and worry all week that everyone I’ve written about hates me.” Across the room, I spotted the smarmy anesthesiologist I mentioned in my last two columns and began to perspire.

“If I were writing about this party, I’d write about all the weird plastic faces here. And that couple.” She looked up at the couple two feet in front of us, a pair of 40-somethings in white who were doing a sloppy Lambada. They started making out and their hands seemed to multiply as they moved over each other.

“Gross,” said Sarah.

“That the forbidden dance. It’s forbidden,” I said referring to the trashy movie of 1990.

She shrugged and I remembered that she’s younger than I am. Probably doesn’t even know who Cliff Clavin is. I folded my arms, embarrassed.

“And I’d write about those women in the matching pirate costumes. What’s with that?”

Two modelly Russians were wearing white ruffly things, cinched by large black belts. “Do you think they’re prostitutes?” I whispered.

“When you see a young woman like that talking to an old fat guy like that, you’ve got your answer,” said Sarah. I thought about my ex-fiancé’s belly and age with respect to my own and wondered if I am as pretty as those girls, or if my virtue is as incontestable as my nose.

Patrick McMullan came by, photographed us, and talked about how his balance was off, how he was getting old. (Not old enough for me!) He and Sarah reminisced about Art Bagel, a joke they’d hatched 10 years ago at Art Basel. Patrick didn’t remember me.

Sarah went to the restroom: “I’ll leave you to your reporting,” she said. Wanting to impress her, I looked around for someone to talk to. I spoke to a few strangers — would you like to know their names now? Their jobs and which ones had food in their teeth? “It’s good to see you, too!” I exploded in the face of the anesthesiologist — and then escaped to the outside, where I saw half a jet fuselage with the word Challenger written on it. A woman ran up the steps to pose for a photo, as if she were getting on her own private jet. NetJets was one of the event's sponsors.

“That’s in poor taste,” I told Sarah when she came out. “Wasn’t the Challenger the space ship that exploded 1986’s first teacher in space?”

We hit the dance floor and Sarah waved neon sticks. I held my sticks, not sure what to do with them, before a drunk girl with an armful took mine too and disappeared.

Sarah told me about her feud with Martha Stewart in the days before she moved on from her party column.

“I was just set up with one of her exes,” I said, trying to keep up.

“What’s with you and all the old guys?”

On the way out, a young woman swayed and hopscotched drunkenly, yelling at her friends behind her to “step it up!” before demanding to know where they were going next. Sarah laughed and I knew what she would write about.

But me? I’d probably write about what it feels like to wake up as a bug. How it makes your dress pinch.