Shooting at the Ends of the Earth and the End of the Night

There are certain images that are indelibly set in the popular culture. No matter how you feel about Bruce Springsteen and his musical legacy, it is hard to deny that the image of him — guitar slung over his shoulder, leaning on Clarence Clemons, who is blowing his saxophone, both looking young and very rock ’n’ roll, circa 1975 — from the cover of “Born to Run” is a certifiable icon.

The man behind that image, Eric Meola, still talks about that photo shoot and what led up to it with the zeal of a true fan. A few decades later, seated in the warmth of his Sag Harbor house on a rainy day before Christmas, he recalled the time he first heard Mr. Springsteen perform.

“It was 1973. I was walking by Max’s Kansas City on Park Avenue near Union Square, where I lived at the time, and I noticed a sign that Bruce Springsteen was playing that night. I had heard a couple of his records and really liked them, so I went to the show. I was completely knocked out, to the point where I said to myself, ‘I want to photograph this person. He’s going to be important.’ ”

Mr. Meola was already an established photographer, a protégé of Pete Turner (now of Wainscott, who is known for his intense and often abstract-looking color photography), and he then had several images on the editorial pages and cover of Time and Life magazines. He had also received his first commercial assignment from Porsche. Yet, he was already chafing from the demands of the corporate clients and looking for outlets where he could enjoy more artistic freedom.

It wasn’t until the following summer, however, that Mr. Meola found himself face to face with the musician. It was raining and they both sought shelter under the awning at the Plaza Hotel before Mr. Springsteen was scheduled to perform in Central Park. “I made an awkward introduction and told him how much I liked his music.”

Mr. Meola continued going to shows in New York and in small venues in New Jersey where there might be just a few people in the audience. “Little by little, he started to realize I was a photographer. I started taking pictures at the shows.” Eventually, he went to Asbury Park to take some portraits and decided he really wanted to shoot Mr. Springsteen’s next album cover.

It took a while to set up. This was a well-documented time of great turmoil for the musician, as he tried to break free of his management and spent most of his days in the studio struggling to make the perfect record he felt he needed to break through as a recording artist.

After a few false starts, Mr. Springsteen showed up with Mr. Clemons at Mr. Meola’s studio, resulting in some 700 photos, amounting to 20 rolls of film, taken in two hours with no assistants. “It was very intense. I had planned out certain things and Bruce had planned out certain things and no sooner were they there, than they were gone.” Mr. Meola said his mantra during the session was to “shoot a lot, not wildly or randomly, but with a lot of variety in the images.” There were several clothing changes and stylized poses.

John Berg, who was the art director of Columbia Records at the time, and who is the subject of a retrospective of the album covers he oversaw at the label at Guild Hall, knew right away that the image that was ultimately used should be the cover.

It took a while to convince Mr. Springsteen. Mr. Meola said it was only recently that he found out from Mr. Berg that “Bruce rejected the cover. His previous album [“The Wild, the Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle”] had a very tight close-up, ‘serious artist’ look, which is what he wanted this time.” If he had rejected the cover outright, “that would have been it, but John convinced him otherwise.”

He said he had never spoken to Mr. Springsteen about it. “We’ve never sat down and gone over the pictures. When I published ‘Born to Run: The Unseen Photos,’ in 2005, I asked if I could use his lyrics, which was a big thing to be asking for, but he let me use them.”

Mr. Meola said, “to this day I can’t believe I shot the cover. It was that powerful of a desire to do it, that I am still pinching myself 35 years later.” He did a follow-up shoot with Mr. Springsteen for “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” but his images were not chosen.

Although it might be expected that there would be some severe rivalry between those who photograph the Boss, as Mr. Springsteen is known, Mr. Meola said they are a friendly group and have become even friendlier since Mr. Meola started an event to raise money for the Community Food Bank of New Jersey, a charity Mr. Springsteen also supports.

Mr. Meola already donates profits from his Springsteen photo books to the food bank, and after the economy crashed a few years ago, he convinced some of those photographers to contribute prints of Mr. Springsteen and his band for a benefit raffle. They included Frank Stefanko, who beat Mr. Meola out for the “Darkness” cover, Annie Leibovitz, and Pam Springsteen, the musician’s sister. At $25 a ticket, the raffle raised $136,000 for the cause. A similar effort this year after Hurricane Sandy raised $118,000 for the same organization. “We get a lot of support from the Springsteen camp and his fan magazines. We sold thousands of tickets,” Mr. Meola said.

After “Born to Run,” he did album photographs for Chaka Khan, Carly Simon, Foreigner, Blue Oyster Cult, and Tony Williams, a jazz drummer and Miles Davis protégé. By this time, however, he already had a thriving commercial photography career with accounts such as American Express, General Motors, Johnny Walker Scotch, and Timberland shoes. It was a nice change from the late hours and excessive lifestyles of the musicians he photographed.

“It takes a lot of energy. You have to hang out with them and need to build up a relationship with them to do it right. You have to go to their houses, keep their hours. Even with Bruce, his hours were night hours. I would have an appointment with him and he wouldn’t be around.”

Mr. Meola balanced his commercial assignments with more personal pursuits. When he was sent to Kenya to shoot a plantation for a Swiss coffee company, for example, he took time to go south to photograph the Masai tribe. “It was these two parallel realities for the next 15 years.”

Then a particularly difficult assignment for Johnny Walker in California, during which several severe winter storms stretched the shoot from 12 to 32 days, caused him to re-examine his career. He had been reading about Burma and decided to go. He said it led to a spiritual and religious metamorphosis.

When he returned, a friend who worked at Kodak asked him what assignments he wanted to do. He told her about an idea he had to photograph the last great places on earth, and was invited to Rochester and offered the chance to shoot pictures all over the world with a new kind of film the company was introducing.

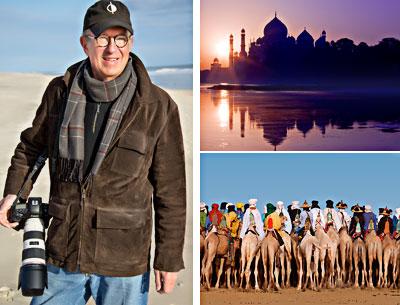

He spent the next three years traveling to places such as the Sahara Desert, India, China, Cuba, and Antarctica. “They didn’t ask for a list, they said you just go where you want to go. So several times a year I would go to these places, deciding to concentrate on a few of importance and interest to me.”

He has been working this way ever since, not quite retired, but making his own assignments and producing books when it seemed appropriate. A couple of days before the interview last month, he had flown back from the Atacama Desert in Chile where he took pictures for a new “Great Places” series in formation and will soon be returning to Antarctica.

He has also recently taken his art into a more abstract realm. “We grow up with the notion of photography as a description of the real world. I feel very strongly that it doesn’t have to be that way. It can just be about abstract color and abstract light,” he said, adding that “a lot of my work is becoming abstract and the subject is color.” It can be as random as opening the camera shutter and waving the lens in the air or taking a picture of a real thing in a way that highlights its abstract qualities.

Home base is Sag Harbor, where he and his wife, Joanna McCarthy, also a photographer, have lived full time for the past decade.

Despite this region’s reputation as a creative draw for artists, for Mr. Meola, being home is his down time, a quiet period for relaxing and planning. He can sometimes be found shooting in his garden if he likes the light on a leaf or sees something budding, “but it’s not my main interest.” The South Fork is “a harder place to photograph in one sense,” he said, “because it’s quieter, a much softer environment. . . . I’ve always been interested in more remote places and more exotic places.”