Sidling Up to Crabs

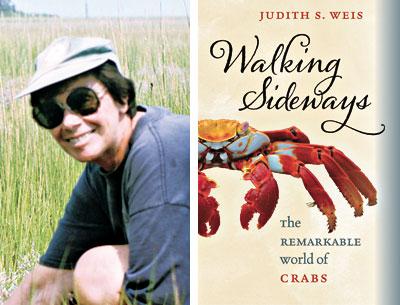

“Walking Sideways”

Judith S. Weis

Cornell University Press, $29.95

Did you know that there are species of crabs that spend their entire lives in freshwater? Or that there are air-breathing land crabs? Or that horseshoe crabs are not true crabs or even crustaceans? Or that the Japanese spider crab can weigh over 40 pounds and sport a leg span of 12 feet?

An alternate title for “Walking Sideways,” by Judith S. Weis, a professor of biology at Rutgers University, could have been “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Crabs (but Were Afraid to Ask).” This richly informative, illustrated tome may be the most comprehensive storehouse of information, outside of a laboratory, on all things crab. Ms. Weis has exhaustively researched the crustacean, and clearly has a fascination and affection that far surpasses most.

This interest dates, she wrote, to a childhood spent summering on Shelter Island. Her research has taken her to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts, and the defunct Ocean Sciences Laboratory in Montauk, as well as into the field — specifically, Louse Point in Springs.

As only about 1 percent of the deep sea has been explored, Ms. Weis wrote, new groups of crabs are still being discovered. Among these discoveries are “four new species of brightly colored freshwater crabs . . . found on the Philippine Island of Palawan” just this year. These newly discovered species, she wrote, “are already under threat from several mining projects.” In 2005, scientists found “a white eyeless crab with long hairy arms and legs living at over 7,000 feet of water near a vent in the South Pacific.” This specimen was found to be a member of a totally new family of anomurans (a group of decapod crustaceans).

Like most of the Earth’s flora and fauna, crabs are part of an interconnected and interdependent web of life. In the chapter titled “Habitats,” she wrote that, “When blue crabs were moved from a salt marsh, one of their major prey — periwinkle snails — flourished, multiplied, and ate up all of the cordgrass. Without the plants to bind sediment and protect wildlife, the salt marsh ecosystem disappeared and became a mud flat. This suggests that the loss of snail predators such as blue crabs may be an important factor contributing to the die-off of salt marshes in the southeastern United States.”

Another at-risk habitat, coral reefs, form part of a symbiotic relationship with crabs: “Trapeziid or guard crabs, such as Trapezius sp., only a half-inch wide, make their home in branching corals and remove sediment onto the coral,” Ms. Weis wrote. “When the researchers removed crabs from sections of the branching corals and allowed sediment to accumulate, most of the corals died within a month.”

There are crabs that live in the open ocean on floating material (the Sargassum or gulfweed crab) and others found on floating species such as sea turtles and jellyfish (the grapsid crab). Ms. Weis wrote about how different crabs are adapted for their particular environment, and takes the reader on an informative tour covering crabs’ evolution and classification, behaviors, unique adaptations, reproduction, and threats to their survival.

There are chapters devoted to form and function, reproduction and life cycle, behavior, ecology, fisheries, and the relationships between crabs and humans. There is even a chapter devoted to the myriad ways in which crabs are cooked and eaten.

While there exist “problem crabs” — invasive species and parasites — there are, sadly, far more “crab problems,” as detailed in Chapter 7. Toxic chemicals, pesticides, oil, industrial chemicals, marine debris and trash, and climate change, in addition to natural hazards such as disease, all threaten these fascinating creatures.

For those interested in these animals — as marine life, as pets, or as food — “Walking Sideways” spans the positive and negative phenomena surrounding and affecting the nearly 7,000 species of crabs.

Judith S. Weis is the author of “Do Fish Sleep?” She lives part time in Springs.