Sins of the Father

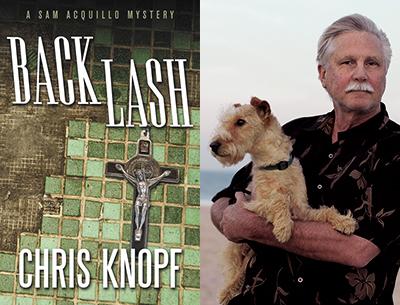

“Back Lash”

Chris Knopf

Permanent Press, $29

Chris Knopf has left the fabulous Hamptons behind for the browner pastures of the Bronx. In “Back Lash,” the seventh installment in what is the original of his several series of crime novels, the geographically pretentious reference has even been excised from the cover, the billing simply reading “A Sam Acquillo Mystery.”

For the best, it seems. Case in point, what might be most appealing about North Sea, the least “Hamptons” hamlet out here, and which Mr. Knopf describes as “the woody area above Southampton,” is its proudly unimproved rumrunners’ network of dirt roads. Our hero, who keeps a cottage there on Little Peconic Bay, where he likes to sit in an Adirondack chair, look at the water, and think on things, does little more than check in on the place as he shuffles the mean streets, chasing leads having to do with the decades-old men’s room beating death of his father.

That scene not only opens the book, it’s its most vivid, as the short-fused French Canadian auto mechanic of Italian extraction settles in with the usual, a cheeseburger with a fried egg on top, a shot of whiskey, and a Miller High Life to nurse while he lingers over his Daily News, folded in quarters for one-handed reading. By the 1970s this borough bar devoid of all niceties had been darkened with age to the point that its woodwork, “a deep mahogany, soaked up what little natural light got through.”

In other words, it’s as dark as the Bronx’s Mother of Divine Providence Church, only more frequented. Inside that “giant pile of European architecture” rising from the wrecked neighborhood “like a forgotten fortress,” Mr. Knopf writes, the gloom “was dense enough to cup in your hands.” Deep in its recesses Acquillo finds meaty Nelson Cleary. Bear-like in his priestly black, he stands conflicted at a crossroads of family histories and plotlines, what with one brother on the City Council and another in journalism, and having given shelter and housecleaning employment to a woman who’d started a second, secret family with Acquillo senior.

But enough of that. These settings become like characters unto themselves — a main reason that readers, or this reader, anyway, are drawn to crime fiction, as with Elmore Leonard’s matchless Detroit novels of the late ’70s, gritty, bare-bones, before Hollywood got to him, or Lawrence Block’s Matthew Scudder, forever killing time in coffee shops and deserted pews.

Sam Acquillo by his own admission lacks many of the more admirable character traits, like patience, so he doesn’t exactly sit around as Scudder did, though you can catch him feeling his breast pocket for a phantom pack of smokes, or sipping bitter coffee on his cheap room’s balcony, so small the chair sits sideways, “staring out at the hotel’s cramped parking lot and the ragged storefronts across the street.”

An M.I.T. grad and former hydrocarbon-processing engineer (hey, someone’s gotta do it), he can also be found pontificating with some insight during his adventures among the cops, perps, accomplices, and informants. On technology, perhaps most memorably, fearing its addictiveness, the “hypnotic pull” of the screen, finally relenting and nagging a librarian into helping with his first Google search of the digital ether, ridiculing his subsequent time spent “messing around on the computer like the rest of the American population” — he considers cigarettes a safer habit.

“You know who’s hard to find on Google?” he’s asked.

“An honest man?” he answers.

Acquillo’s father was an angry man, known to toss a wrench at his son’s head over a difference of opinion about car repair. So Sam plows into the investigation out of innate curiosity, not affection or vengeance-seeking, and in light of the experiences of his girlfriend, who never knew her father, and his cohort in the cold-cases bureau, whose old man committed suicide when she was 18, he comes to see himself as “caught in a conspiracy, conceived by a cabal of dead fathers, each having left children behind to be tormented by their mysteries, their sins against innocence and adoration.”

Heavy stuff, Sam, good thing that dead father left you a little refuge by the bay out in the sticks. Pet your dog, kiss your girlfriend. Biology is not destiny.

Chris Knopf lives part time in Southampton.