Siren Song of the Soviets

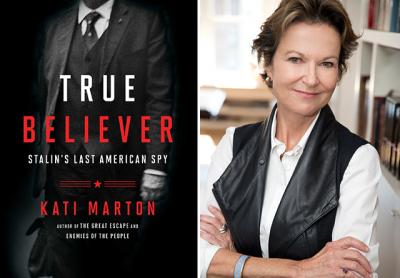

“True Believer”

Kati Marton

Simon & Schuster, $27

Why and how does someone come to embrace a compulsive myth and commit totally to a humanitarian cause for achieving worldwide perpetual perfection? Answering this problem requires an understanding of the subject’s historical context.

Noel Field, the complex “idealist and dreamer” Kati Marton interprets in her forcefully argued new book, “True Believer: Stalin’s Last American Spy,” was affected by injustice and hypocrisy in early-20th-century America. And intertwined with alienating aspects of time and place were individual factors that drove his conversion to Communism, “a faith that imbued his life with meaning.” Personal needs and historical circumstances thus made him a true believer.

Field’s early life foreshadowed this unusual trajectory. He was born in Switzerland, where his Quaker father, descended from antislavery New Englanders, headed a biological research institute. In 1918, father and adolescent son toured horrific battlefields of the Western Front, where “Noel took his father’s unspoken message to heart: Do something to prevent the next one,” by starting a Peace League of Youth at his Swiss school. One of his classmates was Herta Vieser, who would become his wife and continuous political supporter.

In 1921, the elder Field died suddenly. “How differently,” Ms. Marton imagines, “might Field’s tragic life have turned out had his father lived long enough to harness his son’s idealism to a milder faith?”

He did, however, return to his father’s roots when the remaining family moved to Massachusetts and he enrolled at Harvard, earning an honors degree in 1924. Beyond the classroom, he found a different form of education, the sensational Boston trial, conviction, and execution of two Italian-born philosophical anarchists charged with armed robbery and murder. Protesters raged that the pair had been found guilty because of their radical beliefs rather than the crime.

“The case took seven agonizing years to resolve — seven years during which [Nicola] Sacco and [Bartolomeo] Vanzetti languished in prison and young idealists like Noel Field grew more estranged from their country.”

“True Believer” shows that Sacco and Vanzetti’s electrocutions hastened the Communist International. U.S. history textbooks typically discuss this as an example of President Woodrow Wilson’s post-World War I repression of alien radicals. Ms. Marton demonstrates that Lenin’s propaganda tools seized the opportunity to exploit widespread opposition by influencing public opinion through sympathetic spokespersons globally, discrediting America while extolling Russia.

Against this background, Field became a Foreign Service officer posted in Washington, D.C. The nation’s capital magnified contradictions not just between Russia and America, but between American ideals and realities. Everyday life in Washington operated according to Jim Crow codes, which the newly married Fields defied. They lived in a racially mixed neighborhood, had friends of color, and denounced segregation. Field was also leaning more leftward in his thinking, succumbing to the “siren song of the Soviet myth: man and society leveled, the promise of a new day for humanity.”

Believing that Russia promised universal amelioration, more than 40 men and women in F.D.R.’s administration established a secret cell — Apparatus A — to infiltrate the government and transmit stolen secrets to Moscow. In 1934, Field “was rated [by K.G.B. operatives] among the rising young men in the State Department,” well suited to become a clandestine agent.

Looked at from his standpoint, it would be possible to serve the workers’ paradise and stay loyal to the United States. Ms. Marton recounts an evening when Field took a group of comrades to the Lincoln Memorial, where, one of them recalled, he proceeded to sing “the ‘Internationale’ . . . at the top of his voice — in Russian!” Ultimately he could not have it both ways; his spying tied him to Stalin and totalitarianism, and to Alger Hiss and unAmericanism.

“Field, it appears, was an eager but maladroit spy.” On the other hand, Ms. Marton is adept at explaining his eventful career. During the mid-1930s he was back in Switzerland working for the League of Nations Disarmament Section. He served as a league commissioner assisting refugees from Fascist brutality during the Spanish Civil War, which led to the Fields’ foster daughter, Erica Glaser. (Noel and Herta had decided against having children “for the sake of the great cause.”)

Another refugee project was the Boston-based Unitarian Service Committee clinic that they operated after the fall of France. During World War II Field accepted an assignment from the Office of Strategic Services, facilitated by the future Central Intelligence Agency director Allen Dulles, to gather Nazi secrets, information that the double agent could pass along to Russia. But it was an American government association that would prove disastrous for him.

In October 1948, the confessed former apparatchik Whittaker Chambers accused Field and Hiss of having been Communists conspiring with the Russians. The next fall, after being lured to Prague to interview for a Charles University teaching appointment, Field was kidnapped, transported to Budapest, tortured by Hungarian secret police, and forced “into confessing that his rescue of Communists was a cover for recruiting them for Dulles and the other archtraitor, Tito.”

For six terrible years the Fields (Herta had been arrested, too) endured maximum-security prisons. Then, through Washington-Moscow negotiations and C.I.A. use of a Polish defector, they were suddenly released. The Fields did not leave Hungary, though. They gained asylum, moved into an apartment, and he was given a job at The New Hungarian Quarterly. From that position he defended Russia’s use of military power in November 1956 to crush the anti-Soviet rebellion, which killed 20,000 freedom fighters and resulted in mass arrests.

Soon afterward, he and Herta were interviewed by a Hungarian couple, journalists reporting for American wire services who had been held in the same prison at almost the same time as the Fields, Ilona and Endre Marton.

Ms. Marton is their daughter. Her curiosity about this remarkable meeting provided the germ of “True Believer,” and her sourcing of the book benefited from “many hours of conversation with Endre and Ilona Marton.” Additionally, she was able to gain unique oral history accounts from persons involved with Field. And there is even a bit of insider enhancement from her own recollections of Budapest 60 years ago.

Ms. Marton has researched hitherto unavailable private papers as well as library and archival materials. This highlights the historiographical point that her critical perspective on Soviet subversion references recent scholarship. Since the mid-1990s, declassified files and decoded cables have prompted historians to reassess the “witch hunt” trope concerning the government’s post-World War II zealous pursuit of Communists. Ms. Marton interprets this as coming “long past when the witches were dead. In the early to mid-’30s, however, they were very much alive.”

Her writing is characterized by sentences of this sort. Much of the narrative about spying involves cold-bloodedness, and her vivid descriptive passages appropriately evoke terror. Moreover, she renders gripping situations such as cruel show trials and gulag interrogation sessions to great effect.

Ms. Marton’s study is rewarding for its accounts of crucial aspects of modern American and European history, but also for its intriguing implications concerning the power of ideology more broadly. Will there be Noel Fields in other places at other times? If so, could there be different outcomes for those true believers?

J. Kirkpatrick Flack is retired from the University of Maryland, where he taught American history. He lives part time in Bridgehampton.

Kati Marton’s previous book was “Paris: A Love Story.” She has a house in Bridgehampton.