Sisters of Mercy

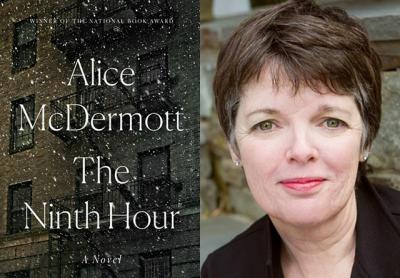

“The Ninth Hour”

Alice McDermott

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $26

“Truth reveals itself . . . it’s really that simple.” These lines are the spine of Alice McDermott’s extraordinary new novel, “The Ninth Hour,” a work astonishing for how compellingly it tells the tales of several nuns who serve an early-20th-century Brooklyn neighborhood, and for how those nuns interact with those in their care, and the mistakes and corrections made by all of these people.

The story begins on a miserable February 3rd. A recently fired trainman sends his wife, Annie, out to the market, pushes the sofa against the front door, then hooks up a hose to the gas oven. When Annie returns, neighbors help her shove the door open and light a match against the darkness. A policeman sees Sister St. Saviour, a Little Nursing Sister of the Sick Poor, as she’s returning to her convent, weary and aching after standing all day asking for alms in the frigid rain. Searching her face, he calls her in. “Softhearted . . . one of us,” the sister thinks to herself about the policeman.

Sister St. Saviour tends to Annie as well as the neighbors. Annie, pregnant, soon has a job in the convent laundry, learning the secrets of ironing and cleaning from the slightly irascible Sister Illuminata — they wash and iron the clothes of the people they minister to and distribute clothing they collect to those in need. The baby, Sally, spends much of her childhood in the basement laundry, she and her mother extremely close.

In her teens Sally determines that she has a vocation and, wearing a novitiate’s veil, follows Sister Lucy on her nursing rounds to people’s homes. The work is grueling, painstaking. Mrs. Costello, who has lost part of her leg to an infected dog bite, is bedridden, obstinate, repetitive. “Sally knew Mrs. Costello’s moods. Sometimes the tale of her catastrophe caused her to flatten her lips against her teeth in bitter anger. Sometimes, as now, retelling the tale merely made her weep. Sometimes it was the neighborhood women she condemned.”

Mr. Costello is a doorman at a local hotel where Sally finds work. In a plot turn, Mr. Costello and Annie begin spending afternoons together. When the nuns discover the trysts, they beg Annie to atone. Otherwise she is damned.

Sally, in an astonishing act, tries to “save her mother’s soul even if it mean[s] the death of her own.” And of course there is so much more that takes place in this narrative. Such complexity in this beautifully wrought, carefully orchestrated book. Everything falls into place. With heavenly sleight-of-hand.

Which is not to say all these nuns are destined for sainthood. One nun admits to herself that she’s jealous of another because the former thinks Sally likes the latter better. The nuns occasionally judge each other harshly for their looks, their actions, their attitudes. Sally is taken aback by Sister Lucy’s analysis of women who fail at their wifely duties. “Sally recalled Sister Lucy saying that if that dog had been drowned as a pup, still Mrs. Costello would have found an excuse. She had married without knowing the duties of married life. Duties, Sally knew, her own mother understood. Perhaps relished.”

Nonetheless, Ms. McDermott has a bit of fun playing personalities off each other, voicing opposing viewpoints. Especially with Liz Tierney, Annie’s best friend. The two of them walked their babies together, calling themselves “empresses.” Liz will have six children, and she adores the life forces, the “busyness,” as well as the messiness of her family’s life. Her attitude about women and men is quite entertaining: “The nuns did more good in the world than any lazy parish priest, she liked to say, especially in arguments with her husband. . . . The priests were pampered momma’s boys, compared to these holy women, Liz Tierney would argue. . . . ‘It’s the nuns who keep things running.’ ”

But Mrs. Tierney, who loves the nuns, “also harbored in her heart the belief that any woman who chose to spend a celibate life toiling for strangers was, by necessity, ‘a little peculiar.’ ”

There’s a wonderful account in Ms. McDermott’s novel — this one historically true because her stories are emotionally as true as true can be — about Jeanne Jugan, a 19th-century French woman who found a blind widow whose family had cast her into the street. She took her home, bathed, fed, and cared for her. Then she discovered another abandoned woman in the streets, and another, and another. Some women, noting what Jugan was doing, came to help her care for the elderly. And soon they founded the Little Sisters of the Poor, going out with baskets to beg for money.

When a rich man who didn’t want to give Jugan money punched her in the face, she rose. “ ‘Yes, but my ladies are still hungry.’ Then he gave her all the money he had.” Charles Dickens came to visit her — and she wangled a big check out of him. When the president of France awarded her a gold medal, she melted it down to feed her ladies.

But then a local priest went to the Vatican, claiming he’d been the one to take in the blind widow, that he’d founded the Little Sisters of the Poor. A plaque proclaiming his accomplishments was placed on the convent. He stopped Jugan from leaving the nunnery to seek donations, ordering her to do housekeeping. She accepted the snubs without rancor. Years after her death, Jugan’s role was uncovered, and a new plaque created. The elderly nun recounting Jugan’s tale, a woman who has taken the name Sister Jeanne, says, “Truth reveals itself. It’s really quite amazing. God wants us to know the truth in all things, she said, big or small, because that’s how we’ll know Him.”

And it is Sister Jeanne’s ultimate sacrifice at the end of this searing work that stays with us.

The Ninth Hour, the time of afternoon prayers, the biblical time of Christ’s death. Surely there has never been as strong and clear-eyed a novel about kindness as Alice McDermott’s “The Ninth Hour.” Winner of a National Book Award for “Charming Billy,” Ms. McDermott is yet again at the height of her formidable powers. This work of art comes to us at a time when, as much as ever, we need a call to compassion.

Laura Wells, a regular book reviewer for The Star, lives in Sag Harbor.

Alice McDermott has been a summertime visitor to East Hampton since she was a child.