From the Slave Quarters

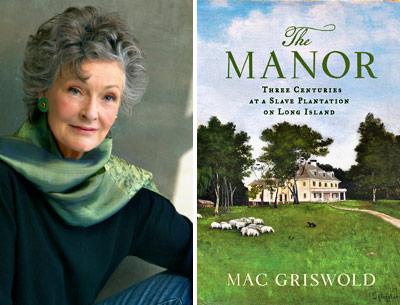

“The Manor”

Mac Griswold

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, $28

“The Manor” is a fresh and invigorating book reporting on 30 years of Mac Griswold’s search for the truth about the secrets of the manor house located on a creek near the north shore of Shelter Island. In 1653, its builder and owner, Nathaniel Sylvester, owned the entire island and ruled it as a European feudal kingdom — a plantation, as it was politely called.

But it is more than the story of this one house and its plantation. The author’s investigations provide a window into the fascinating history of the East End in the 1600s.

As the chairman of the East Hampton Library, I have read (and reprinted) dozens of local histories, and nothing compares to “The Manor,” published this summer. “The Manor,” which has the subtitle “Three Centuries at a Slave Plantation on Long Island,” is not a dry local history. It is not a historical memoir, nor an oral history. Nor is it historical fiction or biography. It is in a class all its own.

Mac Griswold has created an exciting new style of historical writing, engaging the reader in her quest for what actually happened on the East End as it was settled by Europeans in the 17th century. Contrary to most dull histories, Ms. Griswold’s story is written in the first person. The 470-page book reads almost like a detective novel, following the main character as she uncovers clue after clue to solve the mysteries of the manor.

“The Manor” is crammed with original research, and Ms. Griswold effectively smashes the stereotypes and myths presented by prior writers of our local history. She debunks and puts to rest the quaint notion that the East End was settled by those who came here primarily for religious freedom to live in an isolated agricultural utopia.

Now for some details. Ms. Griswold’s investigative report begins in 1984, when, by chance, she finds herself in a small creek on the north side of Shelter Island. Lured by a quiet, stately, and unoccupied yellow manor house on the shore, she tiptoes up the path, peeks in the windows, and is mystified by what she sees.

From that moment, Ms. Griswold relentlessly pursues the history and family secrets that are entwined in the home, held in the same family for 11 generations, right up to the present. Along the way, she is consumed with revealing its past. Her research takes her to Barbados, London, Amsterdam, Ghana, and many places in between where Ms. Griswold searches private archives and government record rooms to find out how and why this manor house stands where it does.

It was the manor house of a plantation of 8,000 acres encompassing all of Shelter Island. Nathaniel Sylvester, born of English parents in 1620 and raised in Amsterdam, struck out with his brother to make his fortune as one of the first international traders frequently crisscrossing the Atlantic, supplying goods to and from Europe and Africa and the New World. Unfortunately, African slaves were part of the trade.

Ms. Griswold documents what many have known for years, but which since the Civil War has been the object of collective amnesia: The North as well as the South had slaves, and some Northerners made fortunes in the sordid slave trade. There are few manor houses in the Northern states, and maybe none other than this one, preserved in the same family with most of its logbooks and records intact (in a secret vault in the manor house, no less!), documenting the interaction among Europeans, the indigenous early Americans, and the slaves ripped from their families in Africa to provide cheap labor in the colonies.

But what made the Sylvester enterprise so profitable was the second plantation established by his family in Barbados. Sugar and molasses were exceedingly valuable in the Northeast, while fruit, vegetables, and sheep and other livestock were even more profitable in the Caribbean. But only Europe could supply muskets, ironworks, and spices. And only Africa the cheap labor. Thus the “triangle trade” we all heard about in school began. Who knew that the God-fearing East End was a major base for the despicable trade in slaves?

Ms. Griswold includes story after story of how the owners of the manor interacted with the world around them. In 12 short pages, she brilliantly describes the struggle by the fanatical clergy in Boston to retain its power over all who settled New England, and how the clergymen were defied by Ann Hutchinson and the devoted Quaker Mary Dyer. We are reminded that Dyer was traumatically expelled from Boston for her Quaker beliefs that undermined the power of the Puritans. She retreated for six months to Shelter Island under the protection of Nathaniel Sylvester, who was an ardent Quaker himself.

But the peace and tranquillity of the manor house was not to last. Dyer decided to return to Boston knowing full well that she would be martyred for her religious beliefs. And the Puritans obliged, hanging her from the big elm tree in Boston Common. To their own horror, the hanging galvanized the attention of King Charles II, who issued a royal writ ordering the Puritans to stop banishing and hanging the Quakers.

The kernel of the book, however, is Ms. Griswold’s enthralling description of the 17th-century slave trade and its impact on the economy of not just Sylvester Manor but the entire region. She calculates that in 1698, slaves were about 20 percent of the population of Suffolk County. This is where Ms. Griswold is at her best. Her research clearly establishes that Nathaniel Sylvester was an active slave trader, transporting as many as 100 slaves at a time to Barbados. When he died, in 1680, he owned 9 slaves on Shelter Island and 15 other slaves elsewhere.

Ms. Griswold’s investigation did not stop with merely perusing documents and archives. She enticed historical archaeologists at the University of Massachusetts to painstakingly uncover and document over a nine-year period the remains of early settlement at the manor, including the slave quarters. All of which is vividly described in the book.

But there is so much more to tell you about, with such little space. But not to worry. The book is so well written and organized that you can read each of the more or less self-contained 20 chapters (about 16 pages each) in separate sittings.

If her investigations and stories about the Sylvester family are not enough for you to acquire this book for your library, the bibliography alone makes it an exceedingly valuable acquisition. Its 27 pages of primary and secondary source material is a staggering collection of items relevant to the history of the East End, an essential part of any library of books for the amateur or even professional historian.

What also makes this book so valuable to both amateur and professional historians is the 16-page index, providing quick access to hundreds of names, places, and subjects in the book. Ms. Griswold also includes a timeline of world events to remind the reader what is happening in the world as the manor is built and grows into the future. And lest the fresh style in which the book is written give the impression that this is not a serious history, there are an astounding 80 pages of chapter notes to provide sources for her research. To top off the wonders of this book, there are numerous maps, diagrams, color photos, and artfully inserted illustrations to help bring the narrative to life.

And for those who think I will now reveal the surprise ending, you are mistaken. You will have to buy the book!

In sum, if you have the slightest interest in how the East End became what it is today and why you enjoy living here, you must read this exciting book. Its first-person style and flair take the reader on an easy journey that will open an astounding new world.

Tom Twomey, a local lawyer and former East Hampton Town historian, is the editor of the East Hampton Library’s five-volume East Hampton Historical Collection Series, the latest of which, “Origins of the Past: The Story of Montauk and Gardiner’s Island,” was published in the spring.

Mac Griswold is a cultural landscape historian whose previous books include “Washington’s Gardens at Mount Vernon.” She lives in Sag Harbor.