Slipping Chains and Time

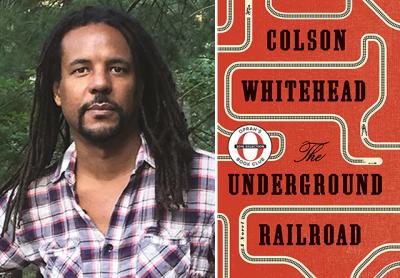

"The Underground Railroad"

Colson Whitehead

Doubleday, $26.95

In Colson Whitehead’s 2001 novel, “John Henry Days,” a black journalist known only as J. attends the annual John Henry festival. J. is a junketeer — that is, a journalist on assignment who enjoys sponging off publishers for free lodging and per diems in exchange for mediocre copy on frivolous subjects. The tension of the novel was in watching Mr. Whitehead juxtapose the journalist’s disaffection with scenes of the real-life exploits of the legendary John Henry. It was clear that Mr. Whitehead, a former journalist, was excoriating himself — for eating at the trough of junk publishing while other African-Americans did important work.

With his new novel, “The Underground Railroad,” Mr. Whitehead no longer needs to take himself to task.

The novel tells the story of Cora, a teenage slave who flees for the North. Early in the novel, Mr. Whitehead depicts life on the plantation with a visceral authority that still has the ability to shock in our jaded era.

“Not long after it became known that Cora’s womanhood had come into flower, Edward, Pot, and two hands from the southern half dragged her behind the smokehouse. If anyone heard or saw, they did not intervene. The Hob women sewed her up.”

But Mr. Whitehead is too smart a writer to make “The Underground Railroad” simply another litany of white atrocities and triumphant freedom. That story has been told countless times, and told well. In this novel, after 60 pages of plantation life scenes (which include a brilliant set piece about a tiny garden plot that Cora protects with brutal determination), the writer finds a completely new way to tell the story of the escaped slave.

Mr. Whitehead, whose novels often brush against the barriers of postmodernism, invents a real — rather than metaphorical — underground railroad, complete with boxcars, tracks, and railway men. (It is interesting that many high school teachers have complained that they bought copies of Mr. Whitehead’s book based on the title and Oprah’s recommendation, only to find that the novel completely upended the historical facts.) And if the reader thinks that such a railway is a one-way ticket to safety, they will have to think again. Mr. Whitehead has a few more tricks up his sleeve.

The author manipulates time and space so that when Cora gets off the railroad in South Carolina she sees a skyscraper, then meets a group of whites who seem accepting of fleeing slaves, but on whom they are in fact conducting genetic experiments. (This hearkens to the Tuskegee incident beginning in the 1930s in which African-American men with syphilis were led to believe they were receiving treatment but were in fact the subject of a medical experiment.) That the reader is not exactly sure what time period Cora is suddenly in only makes the encounter more disorienting and creepy. Stops in Indiana and Tennessee offer different, though equally imaginative, perils.

Still, “The Underground Railroad” doesn’t always keep its momentum; sometimes Mr. Whitehead’s postmodern flourishes seem to get the best of him. Just when you are caught up in the suspense of Cora’s flight, for example, Mr. Whitehead interjects yet another character, taking us backward or forward in time and disrupting the novel’s trajectory. Some of these characters are worth the diversion, such as the brutal white slave hunter Ridgeway (“If niggers were supposed to have their freedom, they wouldn’t be in chains”), while others are less interesting. Of course it may simply be that Cora is so compelling a character — and you are rooting so hard for her to find freedom — that any detour from her story can seem like a narrative misstep.

Nevertheless, there’s no denying that the book is a triumph. Mr. Whitehead has found a new way to tell the story of slavery that seems more real than if he had stuck to the facts. “All art is a lie that helps us see the truth more clearly,” Picasso once said. “The Underground Railroad” fulfills that edict, and is undoubtedly the most audacious and inventive novel of the year.

Colson Whitehead is the author “Sag Harbor,” about his time growing up there.

Kurt Wenzel’s novels include “Lit Life.” A regular book reviewer for The Star, he lives in Springs.