So Many Songs

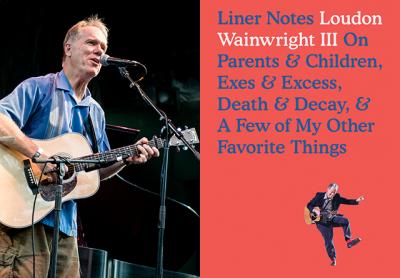

“Liner Notes”

Loudon Wainwright III

Blue Rider Press, $27

The subtitle of the musician Loudon Wainwright III’s memoir, “Liner Notes,” leaves nothing to chance. A longtime visitor to East Hampton and sometime resident of Shelter Island, Mr. Wainwright’s memoir, published on Tuesday (his 71st birthday), is a lengthy rumination “On Parents and Children, Exes and Excess, Death and Decay, and a Few of My Other Favorite Things.”

In “Liner Notes,” the artist, who in 2013 told this reporter that he had performed at the Stephen Talkhouse in Amagansett perhaps 40 times, weaves tales of an oft-meandering career marked by deep ambivalence with candid admissions of personal shortcomings that closely tracked those of his father, the celebrated Life magazine writer and editor and a direct descendant of Peter Stuyvesant.

Indeed, Loudon Wainwright Jr. looms large in “Liner Notes,” as the son frankly itemizes the father’s foibles — excessive alcohol consumption, infidelity, and a somewhat uncomfortable distance and coldness toward his flesh and blood. At the same time, the son’s reverence for his father is illustrated by the inclusion of several of the latter’s Life magazine essays, some of them deeply felt meditations on the “death and decay” of the son’s subtitle.

Mr. Wainwright, with an affection tempered by that dysfunction, recalls a privileged upbringing in 1950s Westchester County, the son of a Northeastern blue blood and a “country girl” from rural Georgia. The tale gets more interesting in the 1960s, a coming of age that, like so many of his generation, included transcendent experiences with LSD and Grateful Dead concerts, which invariably led to a Summer of Love sojourn to San Francisco.

“I hitchhiked across the country with a knapsack, a guitar, a sleeping bag, and one hundred dollars I’d made selling pot,” he matter-of-factly recalls.

Living communally in the Fillmore district, dropping acid and attending concerts, he puts his own music on hold, selling his guitar to pay for yoga lessons. The era also includes a surprising anecdote about Donald Fagan, later of Steely Dan fame but then “a quiet, geeky wannabe hippie,” blowing minds with an impromptu performance of a Ray Charles song on “an old, out-of-tune upright piano” at the Good Karma Cafe. Elsewhere, he takes in a 1964 performance by the Isley Brothers featuring a spellbinding young guitarist named Jimi Hendrix.

At the outset of his career a half-century ago, the singer-songwriter was one of many to which the “new Bob Dylan” tag was affixed by a music industry that, even in that era of unbridled creative exploration, apparently preferred assembly-line product to artist development and originality. (Years later, he playfully confronted this history in a most Dylanesque song called, naturally, “Talking New Bob Dylan.”) When his third album finally yielded a hit, a novelty song called “Dead Skunk,” the artist suffered from the industry’s same default tactic, to categorize. When he did not return to the formula, the record label’s enthusiasm waned. For so many artists, some version of this story is a sad refrain to their careers.

Hence an ambivalence, though Mr. Wainwright concludes his memoir with a deep affection for “the 75-90,” the minutes of the performance itself that make worthwhile all that accompanies the musician’s life: the endless travel, the rootless existence, the many temptations to self-destruction, usually through sense gratification of one sort or another.

Along the way, Mr. Wainwright freely admits, he freely indulged, acting out the traits of his father as he entered and departed relationships characterized by too much drinking, quarrelling, and, inevitably, going astray. In the process, though, Mr. Wainwright demonstrated a remarkable penchant for making his collaborations musical. He and his first wife, Kate McGarrigle, the Canadian singer-songwriter, who died in 2010, produced Rufus and Martha Wainwright, each a successful musician, the former a resident of Montauk. He and Suzzy Roche, who with her sisters perform as the Roches, have a daughter, Lucy Wainwright Roche, who is also a singer. His sister Sloan is a singer and songwriter, and another sister, Martha (known as Teddy), served as his manager.

In 49 mostly brief chapters, Mr. Wainwright intersperses sometimes-lengthy excerpts of his song lyrics alongside the prose. Initially, they are somewhat tedious, a literal retelling of the subject he has just observed, and, if one is unfamiliar with his music, they may seem mundane, void of reflection, metaphor, or even poetry. Paired with his considerable gift for melody, however, the words on the printed page spring to life, and when put to music are revealed as the essence of our shared, tangled human experience — guilt, fear, joy, sorrow, and all the rest. The author dedicates “Liner Notes” to “the family, and all we put us through.”

“The most important people in my life, the principal players, if you will, are members of my family,” he writes. “To a degree, it’s important to escape your family in order to achieve some autonomy in the world, but the reality is that you never quite get away from your ‘loved ones.’ I’m often asked why I’ve written so many songs about the people in my family. The answer is: How could I not? They are the ones who have meant the most in my life, and they continue to have a hold on me, even those who have died. Especially those who have died.”

The excerpt that follows, from a song called “So Many Songs,” underscores the artist’s approach to his life and work, which of course are themselves inexorably intertwined.

I’ve written so many songs about you

This is the last one, after this I’m through

It’s taken so long to finally see

My songs about you are all about me.

Loudon Wainwright III will perform “Surviving Twin,” a show of songs and stories, at Bay Street Theater in Sag Harbor on Sept. 15 and 16 at 8 p.m.